How India's single time zone is hurting its people

- Published

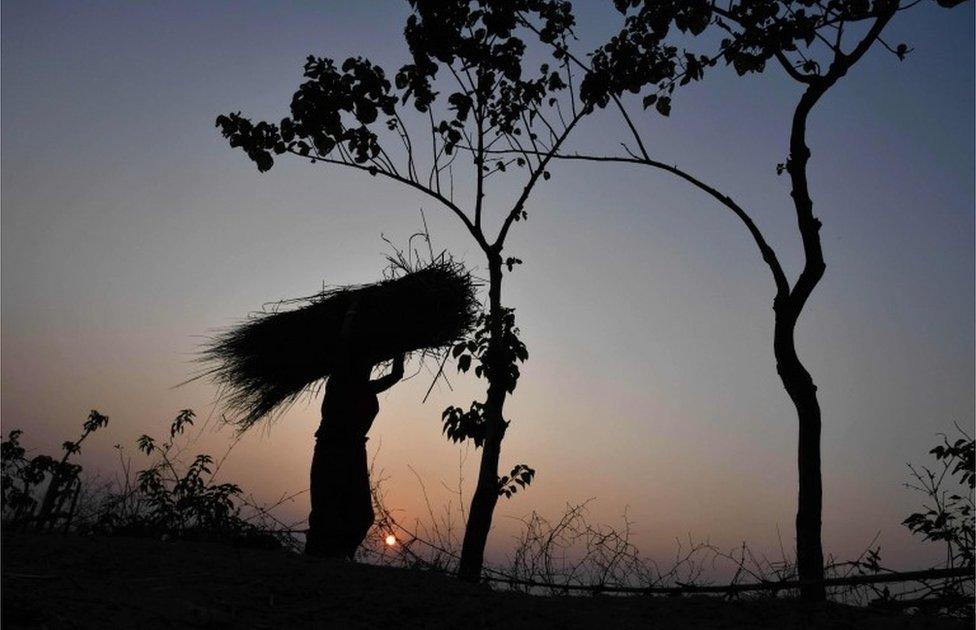

The sun rises nearly two hours earlier in the east of India than in the far west

India's single time zone is a legacy of British rule, and is thought of as a symbol of unity. But not everyone thinks the Indian Standard Time (IST) is a good idea.

Here's why.

India stretches 3,000km (1,864 miles) from east to west, spanning roughly 30 degrees longitude. This corresponds with a two-hour difference in mean solar times - the passage of time based on the position of the sun in the sky.

The US equivalent would be New York and Utah sharing one time zone. Except that in this case, it also affects more than a billion people - hundreds of millions of whom live in poverty.

The sun rises nearly two hours earlier in the east of India than in the far west. Critics of the single time zone have argued that India should move to two different standard times to make the best use of daylight in eastern India, where the sun rises and sets much earlier than the west. People in the east need to start using their lights earlier in the day and hence use more electricity.

The rising and setting of the sun impacts our body clocks or circadian rhythm. As it gets darker in the evening, the body starts to produce the sleep hormone melatonin - which helps people nod off.

In a new paper, Maulik Jagnani, an economist at Cornell University, argues that a single time zone leads to a decline in quality of sleep, especially of poor children. , externalThis, he says, ends up reducing the quality of their education.

This is how it happens. The school day starts at more or less the same time everywhere in India but children go to bed later and have reduced sleep in areas where the sun sets later. An hour's delay in sunset time reduces children's sleep by 30 minutes.

Scientists suggest Manipur, a hilly north-eastern state, should have a different time zone

Using data from the India Time Survey and the national Demographic and Health Survey, Mr Jagnani found that school-going children exposed to later sunsets get fewer years of education, and are less likely to complete primary and middle school.

He found evidence that suggested that sunset-induced sleep deprivation is more pronounced among the poor, especially in periods when households face severe financial constraints.

"This might be because sleep environments among poor households are associated with noise, heat, mosquitoes, overcrowding, and overall uncomfortable physical conditions. The poor may lack the financial resources to invest in sleep-inducing goods like window shades, separate rooms, indoor beds and adjust their sleep schedules," he told me.

"In addition, poverty may have psychological consequences like stress, negative affective states, and an increase in cognitive load that can affect decision-making."

Mr Jagnani also found that children's education outcomes vary with the annual average sunset time across eastern and western locations even within a single district. An hour's delay in annual average sunset time reduces education by 0.8 years, and children living in locations with later sunsets are less likely to complete primary and middle school, the research showed.

Mr Jagnani says that back of the envelope estimates suggested that India would accrue annual human capital gains of over $4.2bn (0.2% of GDP) if the country switched from the existing single time zone to the proposed two time zone policy: UTC+5 hours for western India and UTC+6 hours for eastern India. (UTC is essentially the same as Greenwich Mean Time or GMT but is measured by an atomic clock and is thus more accurate.)

The sun can rise nearly two hours earlier in the east of India than in the far west

India has long debated whether it should move to two time zones. (In fact tea gardens in the north-eastern state of Assam have long set their clocks one hour ahead of IST in what functions as an informal time zone of their own.)

During the late 1980s, a team of researchers at a leading energy institute suggested a system of time zones to save electricity. In 2002, a government panel shot down a similar proposal, citing complexities. There was the risk, some experts felt, of railway accidents as there would be a need to reset times at every crossing from one time zone to another.

Last year, however, India's official timekeepers themselves suggested two time zones,, external one for most of India and the other for eight states, including seven in the more remote north-eastern part the country. Both the time zones would be separated by an hour.

Researchers at the National Physical Laboratory said the single time zone was "badly affecting lives" as the sun rises and sets much earlier than official working hours allow for.

Early sunrise, they said, was leading to the loss of many daylight hours as offices, schools and colleges opened too "late" to take full advantage of the sunlight. In winters, the problem was said to be worse as the sun set so early that more electricity was consumed "to keep life active".

Moral of the story: Sleep is linked to productivity, and a messy time zone can play havoc with the lives of people, especially poor children.