India election 2019: Concern over 'toothless' poll guidelines

- Published

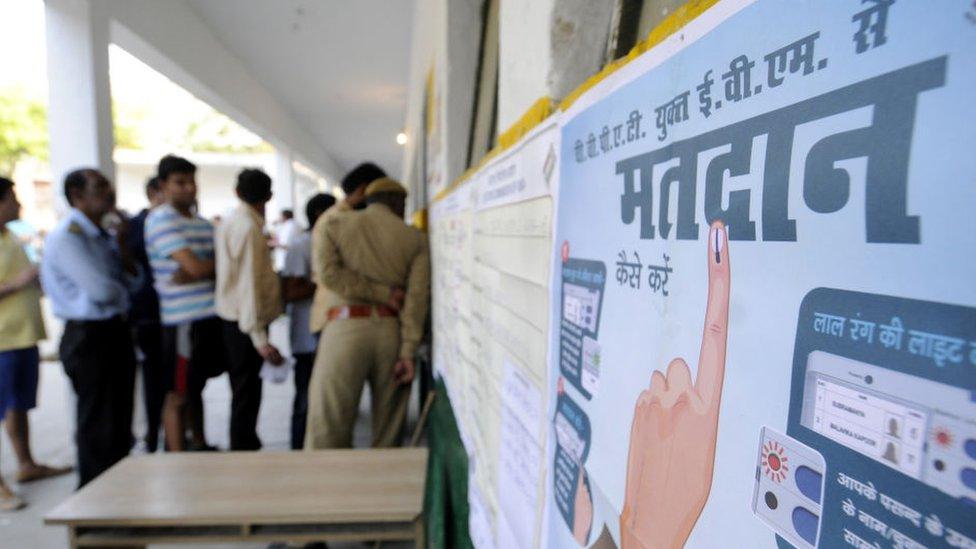

The election commission has to ensure the smooth running of polls

India's Election Commission (EC) is charged with upholding the guidelines governing the world's largest election, but critics have often accused of it being nothing more than a "toothless tiger". Is this really the case? BBC Hindi's Vineet Khare reports.

To say that the election commission has had a challenging year would be an understatement.

In addition to ensuring the smooth functioning of the 2019 general election - the biggest the world has ever seen - it is also expected to ensure that political parties follow guidelines intended to ensure a level playing field for all candidates. This is known as the model code of conduct, external.

The code sets out rules for the "general conduct" of candidates, and also for whichever party is running the government. These include the prohibition of using government transport or resources for campaigning work, and issuing advertisements at the cost of public funds.

It also has a strict set of rules about what kind of campaigning is permissible.

But this year, the limits of all these guidelines have been severely tested, mostly by the country's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Its "unique" campaigning methods have elicited a furious response from opponents and observers, all of whom have complained to the EC.

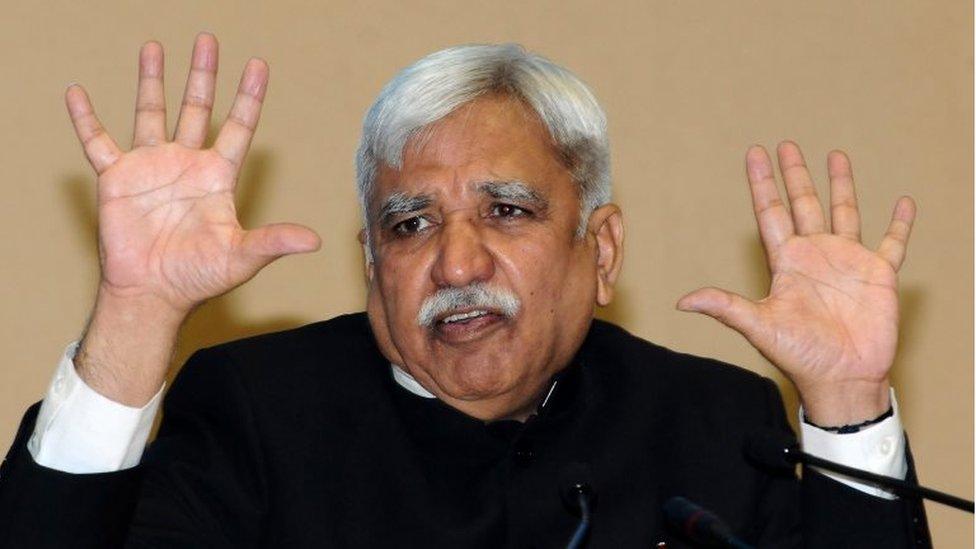

The election commission, led by Sunil Arora, has sometimes been accused of simply throwing its hands up as parties violate guidelines

In the past week it has made two rulings against the government.

On Thursday it said that NaMo TV - a channel dedicated to streaming speeches of Prime Minister Narendra Modi - could no longer broadcast content without its certification. This decision came days after it said that a film about the prime minister - a "biopic" titled PM Narendra Modi - could not be released until the election ended.

The two rulings have served to allay some of the criticisms against the body which has been accused of being too "weak" to take on the government. But there are plenty of other things angering opposition parties and independent observers.

India votes 2019

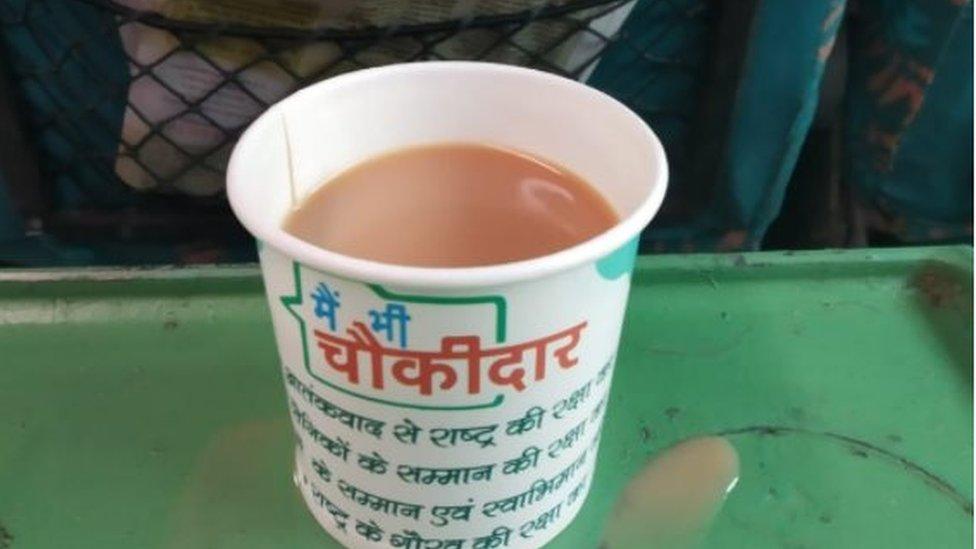

India's crowded trains are serving their passengers tea in paper cups emblazoned with BJP poll slogans, and the country's national carrier, Air India, came under fire for issuing boarding passes emblazoned with ads from a 2018 business summit featuring a picture of Mr Modi.

Then, despite a EC warning against using the military in poll campaigning, pictures of soldiers who died in a suicide attack in Indian-administered Kashmir adorned a stage from where Mr Modi addressed a public rally in the northern state of Rajasthan.

And pictures of an Indian pilot who was captured and then released by Pakistan have been used in political posters. The chief minister of the bellwether state of Uttar Pradesh referred to the army as "Modi's army" while a state governor - a constitutional post - publicly campaigned for the prime minister.

Cups like this, emblazoned with poll slogans, have become an issue

In many of these cases the EC issued notices and wrote letters, containing stern warnings.

But does a censure by the EC matter much in today's politics? Former Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) N Gopalaswami believes "it depends upon how much shame you have".

Other former commissioners the BBC spoke to believe that censure by the EC is effective since the issue gets widely picked up by the media, resulting in a loss of votes for the alleged offender.

But there is no study or evidence to prove this has actually happened.

Sanjay Kumar, the head of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) completely disagreed with this analysis.

BJP MP Sakshi Maharaj said that "whatever the EC does is good" but "it doesn't affect votes". He was pulled up by the EC for blaming Muslims for India's population growth which he said was "causing problems".

But former CEC VS Sampath believes the EC has sufficient powers to send a strong message to the political parties and candidates. He was the man at the helm during the 2014 general election.

Under his tenure, the EC banned BJP leader Amit Shah and the Samajwadi Party's Azam Khan from organising road shows and public rallies in Uttar Pradesh. Both had been accused of giving communally charged and divisive political speeches. The ban on Mr Shah was rescinded after he apologised, but Mr Khan was not allowed to address any rallies.

The model code of conduct is not a law so the EC's powers are limited

The EC also has the power to get police to investigate charges of a criminal nature.

"A large number of criminal cases are filed (during the polls). Unfortunately what happens is that after the elections are over, the election commission goes out of the scene, and it is the state police that has to pursue. It may or may not pursue vigorously," says Mr N Gopolaswami.

Part of the problem, experts say, is that the model code isn't a law, so it doesn't include punishments, is voluntary for all parties, and only remains in place until polls are completed.

"The EC works under limitations. We have suggested so many changes but no party seems interested. No party has mentioned electoral reforms in its manifesto. You cannot entirely blame the EC," said former CES TS Krishnamurthy.

"The election commission should have the power to disqualify and impose monetary penalties. These things are not given any importance by political parties."

- Published8 April 2019

- Published11 April 2019