India air pollution: Will Gujarat's 'cap and trade' programme work?

- Published

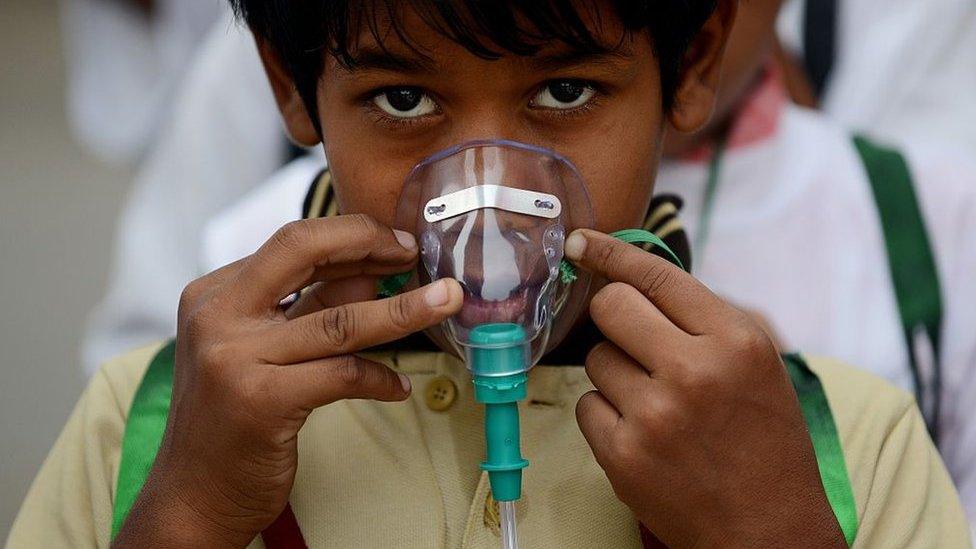

Much of the air pollution is caused by factory emissions

Air pollution contributed to the deaths of at least 1.2 million Indians in 2017 - but a unique pilot scheme to combat air pollution in the western state of Gujarat could prove to be a model for the rest of the country. The BBC spoke to experts to find out more about the world's first ever such experiment.

The concentration of tiny particulate matter (known as PM2.5) in India is eight times the World Health Organization's standard.

These particles are so tiny that they can enter deep into the lungs and make people susceptible to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, making them extremely deadly.

Air pollution in India is caused by fumes from cooking on wood or dung indoors in villages, and a combination of traffic exhaust, soot and construction dust and factory emissions in the cities.

Now Gujarat has launched the world's first "cap and trading" programme to curb particulate air pollution.

Surat is a dense industrial city where textile and dye factories are a major source of pollution

Put simply, the government sets a cap on emissions and allows factories to buy and sell permits to stay below the cap.

It is being launched in the dense, industrial city of Surat, where textile and dye factories are a major source of pollution. Since 2011, local pollution control authorities have been working on the impact of emissions trading in Surat, along with the University of Chicago and Harvard University.

How will this programme work?

The basic commodity in the emissions trading system is particulate matter, which is emitted by industries through their smoke stacks.

Under the emissions trading system, industries must hold a permit for each unit of particulate that they emit, and must comply with the prescribed standard of 150 milligrams per cubic metre of particulate matter released in the atmosphere.

Although industries can trade permits among themselves, the total quantity of these permits are fixed, so that air pollution standards are met.

For example, an industry that finds it inexpensive to decrease emissions is likely to over-comply with the standards - this would allow them to sell its excess permits to another industry that finds it more expensive to decrease emissions.

Both industries benefit by reducing their total costs of compliance, while the total emissions are held constant.

Importantly, this trading system gives firms an incentive to find ways to reduce emissions because they are able to sell any extra reductions to other firms.

These incentives have been shown to prompt firms to innovate so that they find new and inexpensive ways to reduce their emissions.

This standard will be used to set the overall emissions from all the industries that are participating in the pilot programme.

Smoggy skies over the Sabarmati river in Gujarat

Why is this programme being implemented in Surat?

Michael Greenstone, economist and director of the Energy Policy Institute at Chicago (EPIC), says the programme in Surat is a result of a multi-year process that his institute has been working on with the Gujarat Pollution Control Board (GPCB) over the last four years.

In 2015, the environment ministry ordered 17 highly polluting industries - such as pulp and paper, distillery, sugar, tanneries, power plants, and iron and steel - to mandatorily install continuous emission monitoring system (CEMS) devices. They are a network of sensors installed in factories that send live readings of pollution emitted through their smoke stacks.

In the first phase of experiment, some 170 industries installed the devices, which cost anywhere between $2,500 and $7,000 (£2,000-£5,600).

"We worked with GPCB and the industries extensively on how to understand and use this data for regulation," Dr Greenstone says.

Highly polluting industries in India have been asked to install emission control systems

"In the Gujarat experiment, we are working with textile, paper and sugar manufacturing industries."

Can this programme be scaled up in a country as vast as India?

The state's pollution board set this up as a pilot so that whatever is learnt here can be applied to help the operation of the market, says Dr Greenstone.

If successful, there will be a strong case for expanding this regulatory approach to other parts of Gujarat and other states in India.

"Particulate air pollution is shortening lives in India, so if the pilot is successful there is a terrific opportunity for a win-win by scaling up emissions trading in order to reduce industries' compliance costs and to improve air quality which would ultimately [improve] people's health," he adds.

Will this ambitious programme work?

Siddharth Singh, energy expert and author of The Great Smog of India, says the emissions trading scheme has the potential to work.

"Firstly, unlike in other countries, emission trading schemes are not a politically sensitive topic, so it could quietly be tested and scaled up if it proves to be successful. Secondly, India has some experience in running a similar scheme."

India's Bureau of Energy Efficiency has been running a programme to improve industrial energy efficiency. It targets some 500 large users of energy across India and encourages trade in energy efficiency certificates. This has led to decreased energy use and emissions, as well as cost savings.

A hair-raising drive through the Delhi smog

"India is only testing the trading programme at the state level," he adds.

"There is nothing to lose here, even if the pilot fails. But if it succeeds, it could be scaled up and prove to be a great policy tool to address particulate air pollution in India."

- Published2 May 2018

- Published3 May 2019

- Published23 October 2018