Manu Gandhi: The girl who chronicled Gandhi's troubled years

- Published

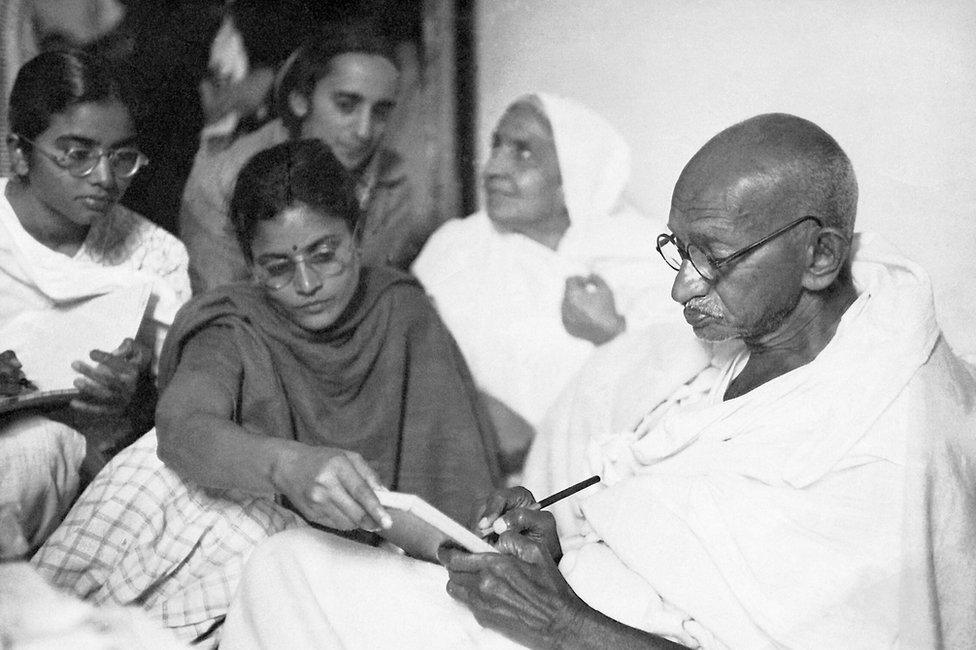

Manu was Gandhi's grand-niece

On the evening of 30 January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi stepped outside the house of an Indian business tycoon in Delhi where he was staying and walked to a prayer meeting in the garden.

Accompanying Gandhi, as usual, were his grand-nieces, Manu and Abha.

As the 78-year-old leader climbed the steps of the prayer platform, a man in khaki emerged from the crowd, pushed aside Manu, pulled out a pistol and pumped three bullets into the frail leader's chest and abdomen.

Gandhi fell, invoked the name of a revered Hindu deity, and died in the arms of the woman who had become his confidante, caregiver and chronicler in his troubled and turbulent final years.

Less than a year earlier - in May 1947 - Gandhi had told Manu with chilling prescience that he wanted her to be a "witness" when his end came.

At just 14, Manu had become one of the youngest prisoners of India's struggle for independence. She joined Gandhi, who had been jailed after his demand to end British rule, and ended up spending nearly a year - between 1943 and 1944 - in prison.

She also began writing a diary.

For the next four years, the teenage prisoner turned into a prolific writer.

Twelve volumes of Manu Gandhi's diaries are preserved in India's archives - written in Gujarati in ruled notebooks, they contain her own writings, Gandhi's speeches (which she wrote as he spoke) and letters, as well as her "English work book".

Now they have been translated into English by Gandhi scholar Tridip Suhrud and published for the first time ever.

Manu became Gandhi's confidante and chronicler in his later years

Her diary, a constant companion, fell out of her hand when Gandhi collapsed on her after the fatal shooting. After that day, she stopped keeping a journal, and instead, wrote books and delivered talks on the leader until her death in 1969 at the age of 42.

The first set of her diaries offers extraordinary insight into a precocious and observant young girl, both devotee and budding chronicler, keenly recording the everydayness of life in captivity.

She also reveals herself as a tireless caregiver to Gandhi's wife, Kasturba, whose health is failing fast.

Manu's early journal entries reveal what appears to be a joyless and regimented life.

It's a never-ending grind of daily duties - cutting vegetables, preparing food, massaging Kasturba and oiling her hair, spinning thread, reciting prayers, cleaning utensils, weighing herself on selected days and so on.

"But you have to remember, she, along with Gandhi and his wife and associates, are in prison. They have voluntary obligations as prisoners. Life might seem joyless and coercive, but she is also learning the rules of ashramic (a religious retreat or a monastic community) way of life that Gandhi practised," Dr Suhrud told me.

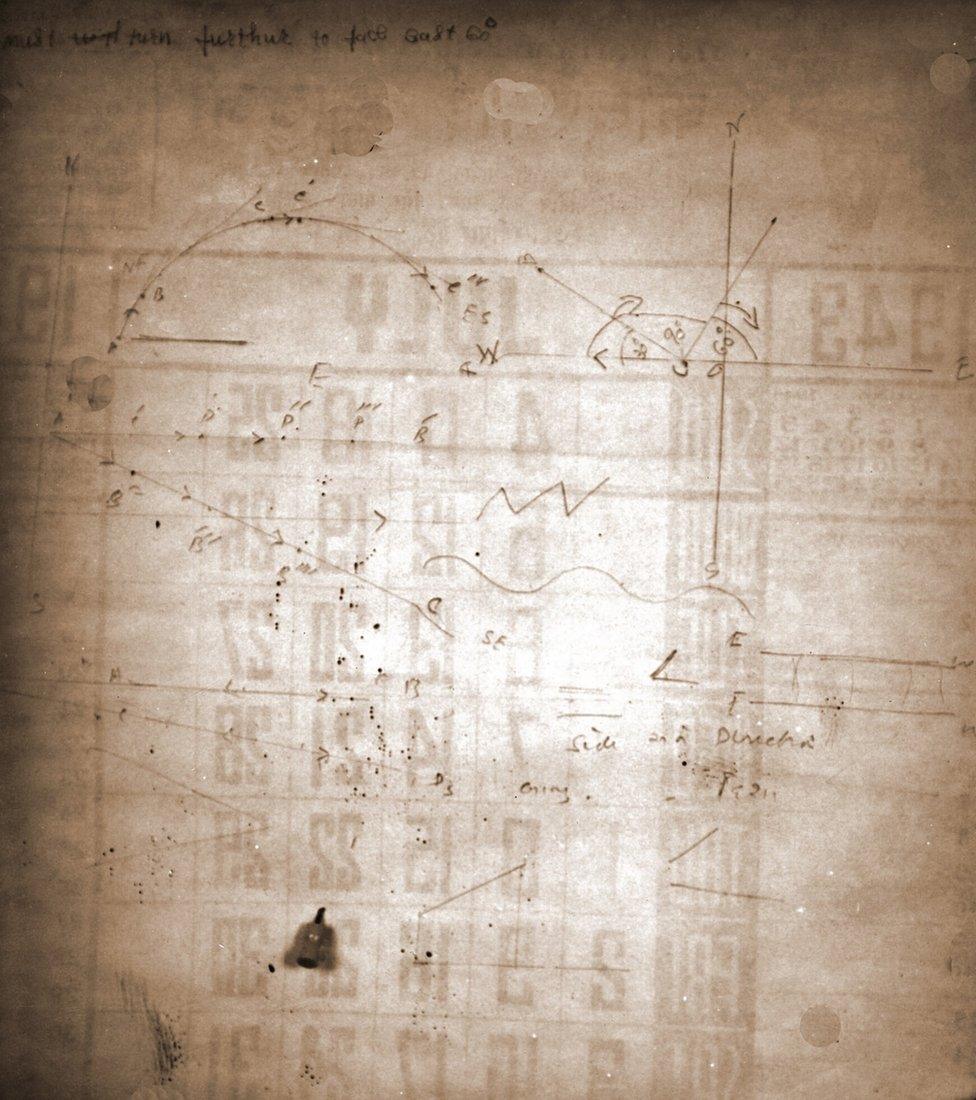

Manu learnt geometry under Gandhi's guidance in prison

Not formally educated, Manu, under Gandhi's guidance, learns English, grammar, geometry and geography. She begins reading the epics and Hindu scriptures. She finds out "where the War [WW2] is being fought" by looking at a map book. The teenager also reads about Marx and Engels.

Grammar lessons take up a lot of study time. "Today I learnt about declinable (changing) and indeclinable (unchanging) adjectives and about predicative and sub-predicative adjectives," she writes about a lesson.

But prison life with Gandhi and his associates is not entirely desultory.

Manu listens to music on the gramophone, goes out for long walks, plays "ping pong" [table tennis] with Gandhi and carrom with Kasturba, and learns to make chocolate.

She writes of how Gandhi's associates in prison plan to dress up like Roosevelt, Churchill and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, in what appears to be readying for a fancy-dress programme of sorts. Gandhi rejects it because he doesn't like "such enactments".

The diaries are also permeated by tragedy. Her writings are bookended by two deaths that shook Gandhi: his closest aide Mahadev Desai, regarded as the greatest chronicler of the leader's life, and Kasturba.

There are heart-wrenching accounts of the days leading up to Kasturba's death in February 1944.

One night she tells her husband that she is in great pain, and "these are my last breaths".

"Go. But go with peace, won't you?" Gandhi tells her.

Manu's entries detail the days leading up to Kasturba's death

And when Kasturba passes away on a winter evening, her head in the lap of her husband, Gandhi "closes his eyes and places his forehead on her as if he were blessing her".

"They had spent their lives together, now he was seeking final forgiveness and bidding her farewell… Her pulse stopped and she breathed her last," Manu writes.

As Manu becomes a young woman, her diary entries are longer and more thoughtful.

She is candid about Gandhi's most controversial and unfathomable experiment - when he asked Manu in December 1946 to join him in bed as he slept "to test, or further test, his conquest of sexual desire", in the words of biographer Ramachandra Guha. (Gandhi had married at 13, and taken a vow of celibacy when he was 38 and father of four children).

The experiment lasted barely two weeks and invited widespread opprobrium, but we will have to wait for the forthcoming volumes to find out what she thought about it.

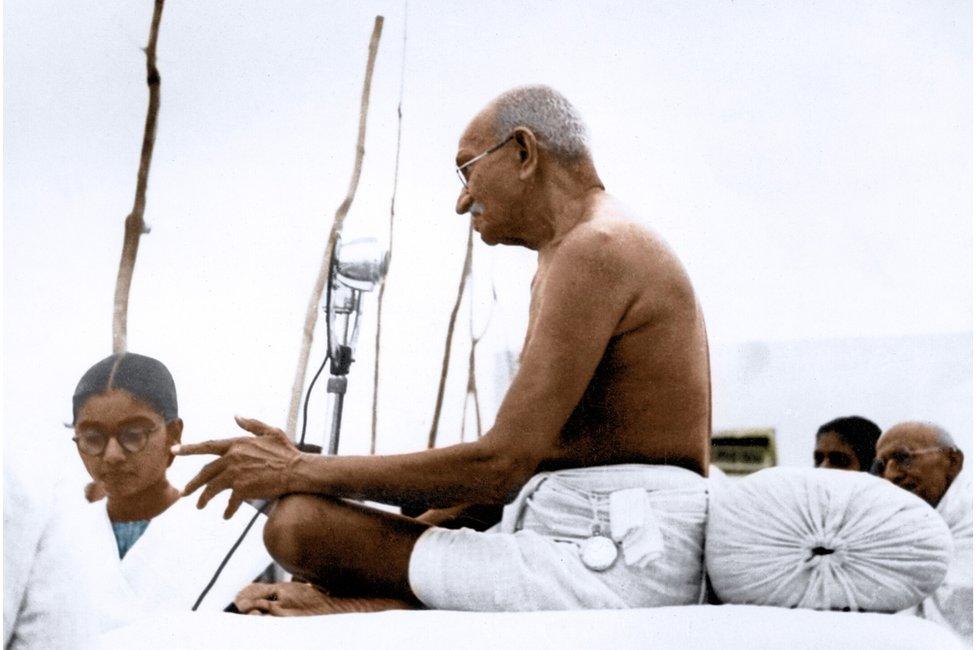

Manu stopped keeping a journal after the day Gandhi died

In the end, Manu Gandhi comes across as an earnest and resilient person, mature beyond her years, discerning, and completely capable of asserting herself in front of one of the world's most charismatic and powerful leaders.

"It is not easy to be with Gandhi in his last phase of life - he has grown old, times are difficult, his wife is dead as are his close associates. To Manu, we owe a lot of our understanding of Gandhi's last days. She's a chronicler, record-keeper and a historian," says Dr Suhrud.

That is quite true.

"Churchill is convinced that I am his biggest enemy," Gandhi tells Manu in 1944. "What is one to do? He believes that he would not be able to suppress and control the country if I were to be kept out of prison. But even, otherwise, they will not be able to suppress the country. Once people acquire confidence, they will not forget it. I consider my work to have been more."

Three years later, amid a bloody partition, India gained freedom.

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Follow Soutik on Twitter at @soutikBBC, external

- Published17 September 2015

- Published13 March 2015

- Published11 January 2016