Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo: The Nobel couple fighting poverty

- Published

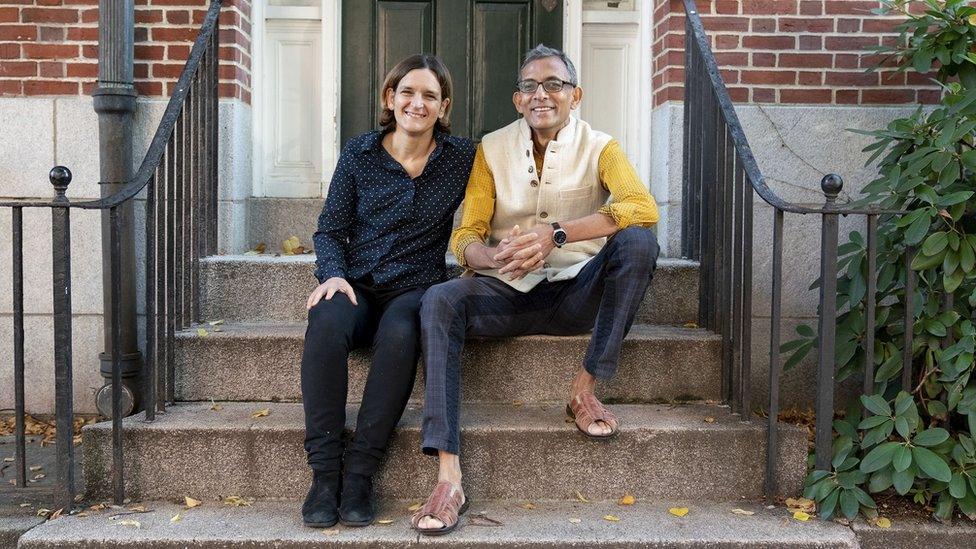

Banerjee and Duflo won the Nobel Prize for their work on alleviating global poverty

For the past two decades, the world's most-feted economist couple has tried to understand the lives of the poor, in "all their complexity and richness". And how an inadequate understanding of poverty had blighted the battle against it.

On Monday, Abhijit Banerjee, 58, and Esther Duflo, 46, won the Nobel Prize in Economics, along with economist Michael Kremer, for their "experimental approach to alleviating global poverty". More than 700 million people live in extreme poverty, according to World Bank.

Both Mr Banerjee and Ms Duflo are professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Ms Duflo is the second woman to be awarded a Nobel in economics.

The Indian-born Mr Banerjee and Paris-born Ms Duflo grew up in completely different worlds.

Esther Duflo was six when she read in a comic book on Mother Teresa that described Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) as an overcrowded city where each resident lived on a 10 sq ft space. At 24, when she finally visited the city as a graduate student at MIT, she instead found trees and empty pavements and little signs of the misery depicted in the comic book.

At six, Abhijit Banerjee knew exactly where the poor lived - little shanties behind his home in Kolkata. The children there seemed to have a lot of time to play and would beat him at any sport, leaving him jealous.

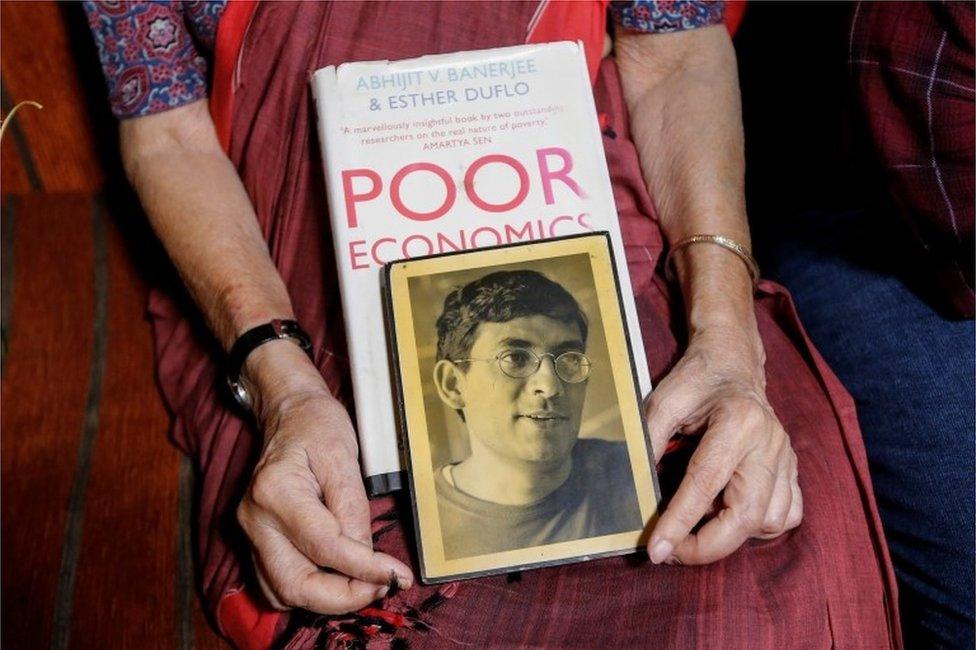

"This urge to reduce the poor to a set of clichés has been with us for as long as there has been poverty. The poor appear, in social theory, as much as in literature, by turns lazy or enterprising, noble or thievish, angry or passive, helpless or self-sufficient," Mr Banerjee and Ms Duflo wrote in their seminal work, Poor Economics, which examined the real nature of poverty and how the poor reacted to incentives.

"It is no surprise that the policy stances that correspond to these views of the poor also tend to be captured in simple formulas: 'Free markets for the poor', 'Make human rights substantial, 'Deal with conflict first', 'Give more money to the poorest', 'Foreign aid kills development' and the like."

The problem, the couple said, was that the poor get admired or pitied. They are also not considered knowledgeable, and that there is nothing interesting about their economic existence.

Millions of Indians remain vulnerable to income shocks

"Unfortunately, this misunderstanding severely undermines the fight against global poverty: Simple problems beget simple solutions. The field of anti-poverty policy is littered with the detritus of instant miracles that proved less than miraculous."

The need was, they observed, "to stop reducing the poor to cartoon characters and take the time to really understand their lives, in all their complexity and richness".

So the couple decided to begin work on the world's poorest and how markets and institutions work for them. In 2003, they founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-Pal) at MIT to study poverty. (The two worked together for a long time before getting married in 2015.)

Over the years, helped by field studies using randomised trials in India and Africa, they tried to make sense of what the poor are able to achieve and where and for what reason they require a nudge. Mr Banerjee says he and Ms Duflo have been involved in about "70 to 80 experiments" in any number of countries.

They looked at what the poor buy, what they do about their children's health, how many children they choose to have, why their children go to school and yet not learn much and why microfinance is useful without being a miracle that some people make it out to be. Or whether the poor were eating well, and eating enough.

Some of their work on how the poor consume food is fascinating. They questioned assumptions like the poor eat as much as they can. Using an 18-country data set on the lives of the poor, the economists found that food represented 36-70% of the consumption of the extremely poor living in rural areas and 53-74% among their urban counterparts. Also that when they did spend on food, they spent in on "better-tasting, more expensive calories" than micronutrients.

Banerjee grew up in Kolkata and co-authored his book, Poor Economics, with Duflo

Nutrition is a conundrum in developing countries. The couple argue that things that make life less boring are a priority for the poor - a TV set, something special to eat, for example. In one location in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan, where almost no one had a TV, they found the extremely poor spent 14% of their budget on festivals. By contrast, in Nicaragua, where 56% of the poor households in villages had a radio and 21% owned a TV, very few households reported spending anything on festivals.

Their work also suggested governments and international institutions need to completely rethink food policy. Providing more food grains- which most food security programmes do - would often not work and help little for the poor to eat better because the main problem was not calories, but other nutrients.

"It is probably not enough just to provide the poor with more money, and even rising incomes may not lead to better nutrition in the short run. As we saw in India, the poor do not eat any more or any better when their income goes up; there are too many pressures and desires competing with food," they observed.

One of their more interesting experiments was trying to understand the poor learning outcomes of children in schools in the developing world.

"We ran experiments where you change a bunch of inputs, like changing the way the teaching happens or change the books or change the timing. And it turns out that what's really critical is that the kids should have some time when they can catch up with the material they have missed, something that is excluded from most school systems in the developing world."

The couple believe there are no magic bullets to end poverty. Instead, there are a number of things which could help improve their lives: a simple piece of information can make a big difference (what is the easiest way to get infected with HIV); doing the right thing based on what we know (cheap salt fortified with iron and iodine); and helpful innovations (microcredit or electronic money transfers using mobile phones).

They hold out hope that "poor countries are not doomed to failure because they are poor, or because they have had an unfortunate history". What often needs to be fought, they say, is "ignorance, ideology and inertia".

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Follow Soutik on Twitter at @soutikBBC, external

- Published11 October 2019

- Published14 October 2019

- Published14 October 2019

- Published10 October 2019

- Published24 July 2013