Why India wants to track WhatsApp messages

- Published

Privacy activists are worried that the new rules could be misused to curb free speech

India's plan to mandate the monitoring, interception and tracing of messages on social media has alarmed users and privacy activists - as well as the companies running the platforms. Prasanto K Roy looks at the potential impact of such a move.

The country's information technology ministry will publish, by January 2020, a new set of rules for intermediaries: platforms that allow people to send, or share, messages. It is a sweeping term, which also includes e-commerce and many other types of apps and websites.

The move is in response to an explosion of fake news that has caused mob violence and led to more than 40 deaths in 2017 and 2018. Most frequent were rumours about child kidnappers, circulated on WhatsApp and other platforms. Those messages, with no basis in fact, caused mobs to lynch innocent passers-by.

Such "forwards" spread to tens of thousands of users in hours, and became nearly impossible to counter once they had spread.

In one example in 2018, the victim of mob violence was a man who had been employed by government officials to go around villages with a loudspeaker and tell locals not to believe rumours being spread on social media.

There are more than 50 documented cases of mob violence triggered by misinformation spread over social media in India in the last two years. Many platforms, including Facebook, YouTube, and Sharechat, a vernacular language social media start-up and app, play a role.

But the Facebook-owned WhatsApp is by far the most popular of the platforms. With India accounting for 400 million of its global base of 1.5 billion users, it ends up being the focus of discussions on the spread of misinformation.

After a spate of rumour-driven mob violence in 2018, the government had asked WhatsApp to help halt the spread of "irresponsible and explosive messages" on its platform. The platform took several steps, including limiting the number of forwards allowed to five at a time, and putting a "forwarded" tag on those messages.

Not enough, said the government, which now wants WhatsApp to use automated tools to monitor messages, as China does, to take down specific messages. It also wants the company to trace and report the original sender of a message or video.

India's attorney general has told the Supreme Court in a related case that social media companies had "no business to enter the country and carry on if they can't decrypt information for investigative agencies, in cases of sedition and pornography, among other crimes".

"See, they [social media companies] have even gone to court to stop us," a government official told me off the record.

He added that online surveillance in China is far deeper and more sweeping. He is right about that: on its popular WeChat platform, messages famously disappear if they contain banned words.

The India WhatsApp video driving people to murder

WhatsApp says the steps it has taken are working.

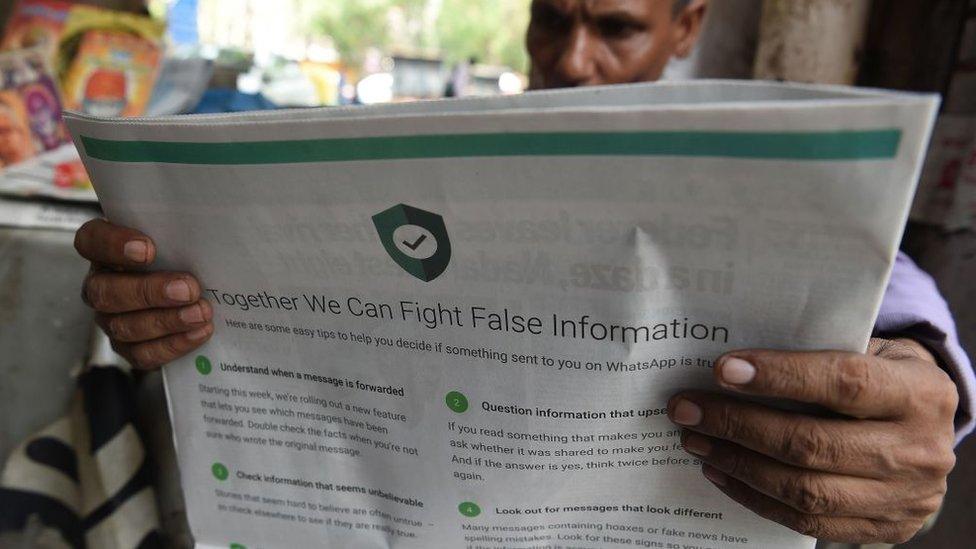

The labels and limits have reduced the number of forwarded messages on the platform by 25%, a spokesperson said. She added that the company actively bans two million accounts a month for "engaging in bulk or automated messaging", and runs a big public education campaign that has reached hundreds of millions of Indians.

Meanwhile, privacy activists are most worried about the demands to "trace" the original sender of a message.

The government says it wants to trace messages that cause violence and deaths, but activists fear it will then track down critics, with a chilling effect on free speech.

This is no unfounded worry, given the spate of cases where those criticising government actions, external, such as its crackdown in Kashmir last August, or those writing a letter of protest to the prime minister, external, end up facing a sedition charge.

"What [they want] is not possible today, given the end-to-end encryption we use," says Carl Woog, WhatsApp's global head of communications, told journalists in Delhi in February.

"It would require us to re-architect WhatsApp, leading us to a different product, one that would not be fundamentally private. Imagine if every message you sent was kept with a record of your phone number. That would not be a place for private communications."

The new rules could have sweeping effects on various platforms

Since 2011, India's laws have allowed platforms some safe harbour. A phone company cannot be held responsible for what its customers discuss over its phone lines; nor an email provider for the content of emails a person sends to another.

As long as the company complies with laws, such as sharing phone records on demand with the authorities, it is safe from legal action. The new proposed rules will make conditions for such safe harbour tougher.

Complying with the proposed rules would weaken the apps or platforms globally, given the difficulties of maintaining different apps for different countries.

And that's not the only problem. The draft rules demand a local India office for any platform which has more than five million users in India. This is ostensibly to find someone to hold accountable when there's a problem.

WhatsApp says its steps to combat the spread of rumours is working

But India's technology laws define intermediary in a sweeping manner, spanning any platform used to share information.

So all of this would end up affecting others too: Wikipedia being an example of a platform that might have to shut down access to Indians, if such a law is enforced. It's also not clear what would be done if a messaging platform, such as the increasingly popular Signal or Telegram, did not comply with this rule.

It's likely that internet service providers would then be directed to shut down access to them.

While privacy activists have taken a hard stance against the contentious provisions - monitoring and traceability - public policy professionals say the government is keener to find a solution than to shut down or seriously disrupt platforms.

"They all use WhatsApp: bureaucrats, politicians, cops," the India policy head of a global tech company told me. "No one wants to shut it down. They just need to see WhatsApp taking more serious steps to tackle a real, serious problem."

Like many others, though, he wasn't able to spell out what those steps should be.

Prasanto K Roy (@prasanto) is a technology writer

Read more on technology in India:

- Published19 July 2018

- Published20 July 2018