Ethical hacking: The challenges facing India

- Published

The vulnerability risked the leakage of millions of patients' health information

A bug discovered in a government health portal last year left data of nearly two million Indian patients unguarded. The recovery has highlighted the need to encourage ethical hacking in a country which is digitising its infrastructure rapidly, writes Nilesh Christopher.

One year ago, India's state-run health portal - which allows users to book online appointments at government hospitals - left exposed a part of its website.

This meant that the personal details and health information of nearly two million users could have leaked.

Security researcher Avinash Jain discovered the vulnerability in the Online Registration System (ORS) in August 2018.

He was able to access details such as the patient's full name, address, age, mobile number, history of appointments made via the portal, patient ID, partial Aadhaar number (a unique biometric identification number) and details of diseases ailing an individual.

"The bug would have allowed any attacker to access details of patients who had booked an appointment in any of the 237 registered [government] hospitals," said Mr Jain.

At the time, he reported the vulnerability to the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In) and the flaw in the government portal was patched in October last year. CERT-In is an office within the ministry of electronics and information technology which deals with cyber security threats.

This correspondent has seen the email correspondence between the researcher and CERT-In from last year.

According to Mr Jain, the incident highlighted the need to encourage ethical hacking in India.

In 2015, the country launched the ORS health portal as an easy way for users to book online appointments and skip long queues at government hospitals.

Mr Jain was able to fish out patient details of Delhi's AIIMS hospital

Any Indian user could book an appointment on the portal by using their biometric identification number.

It was a simple vulnerability where by tampering with the patient ID linked to a specific user on the portal, Mr Jain was able to gain access to medical and personal data of several others registered on ORS.

"The bug allowed attackers to not only access a patient's appointment details, but also cancel appointments set up at specific hospitals," Mr Jain said.

To check the severity of the bug, he picked India's largest government hospital - the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Delhi - to see if he could fish out details of patients.

He found more than 18,000 patient details belonging to the premier hospital and "was able to access the details of appointments made at any given date and time since the service was launched".

This correspondent could not independently verify if the bug was exploited and if any data was stolen in the three years between 2015 and 2018, when the vulnerability was finally fixed.

"Stolen medical patient records are sold at 10 times the value of credit card information on the dark web," said Rajesh Maurya, a cyber security analyst.

"This stolen patient information is usually sold by individuals to those who use it to submit false insurance claims, prescribe restricted drugs, get their hands on someone else's prescription or to sell as a patient profile on the dark web to get medical services," Mr Maurya added.

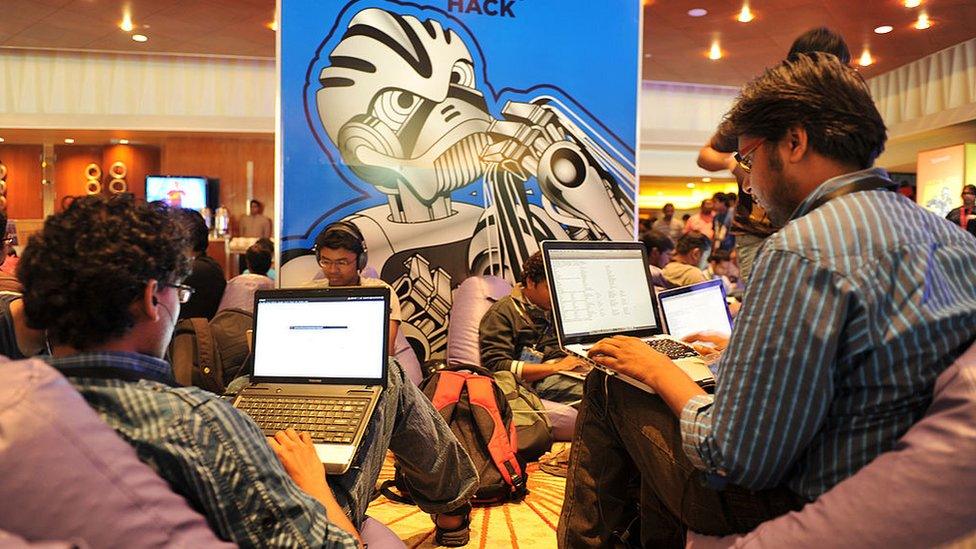

Some ethical hackers say they fear retribution from the government if they disclose vulnerabilities in systems

The global healthcare industry, which manages critical patient data, has often been a prime target for cybercriminals.

Last year, the Singapore government was subject to a high-profile breach that ended up exposing health information of 1.5 million people. The UK's public healthcare provider the National Health Service (NHS) had a data breach last year that affected more than 150,000 patients.

While there are hackers who exploit bugs and gain illegal access to data, Mr Jain says ethical hackers like him who responsibly disclose critical bugs are not always appreciated.

"The Indian government doesn't appreciate skilled bug hunters - despite the fact that we help to make data more secure," he added.

A common feature at hacker conferences in India is the discussion of the legal risks of disclosing vulnerabilities - especially when the bug is related to government agencies.

"Leaks of vulnerabilities have prompted government agencies to issue notices and in some case, even register complaints against researchers. The risk of legal repercussions always exists," Apar Gupta of Internet Freedom Foundation, a non-profit watchdog, said.

As India seeks to digitise a large part of its infrastructure and make government services available online for several of its e-governance initiatives, the risk of cyber-attacks on portals which host sensitive user information increases.

Read more about technology in India:

As per information reported to and tracked by CERT-In, more than 300,000 cyber-security incidents were reported in 2019 - a steep increase from a 50,362 incidents in 2016.

This is where security researchers or ethical hackers become increasingly important because they can help protect against possible attacks and access flaws in the digital infrastructure.

Srinivas Kodali, a security researcher who has exposed flaws in the Unique Identification Authority of India, says the relationship between the Indian government and researchers "is complicated".

"They [government] always fix the issue if it is a critical bug. But they may or may not let you know about it. Sometimes they are thankful and sometimes they complain about your meddling in their affairs," he said.

What many researchers, including Mr Jain, want is for their efforts to be acknowledged and possibly have a "hall of fame" list online of all the researchers who have responsibly disclosed flaws in the digital assets of the government.

India ranks as the top hacker location globally, where Indian 'white hat hackers' or bug bounty hunters made $2.3m (£1.7m) discovering bugs in 2019.

WATCH: The teenage millionaire hacker

Companies pay 'white hat hackers' to hack their websites to find weaknesses in their security systems. Bounty hunters earn rewards for reporting vulnerabilities in international software companies where the culture of responsible bug disclosure is encouraged.

But India currently does not have any law that protects security researchers who responsibly disclose bugs.

The Indian Information Technology Act, external clearly states that any individual who gains unauthorised access to a computer resource is guilty or liable. Since the crime is defined in the context of unauthorised access, many researchers fear retribution from authorities, which prevents them from reporting flaws.

With no well-established protocol at the federal or state level to deal with vulnerability reporting, it often carries an element of risk.

"This can be addressed by making legal amendments to the law. Further, operating practices and policy framework can also be developed to close such vulnerabilities by a progressive bug bounty programme," Mr Gupta said.

Nilesh Christopher is a Bangalore-based technology writer

- Published27 May 2019

- Published15 November 2019