Coronavirus: 'India's healthcare system failed my family'

- Published

India is witnessing a surge in Covid-19 infections which has brought its health system to the brink of collapse. BBC Gujarati's Roxy Gadgekar describes how his own family was devastated by coronavirus.

When my sister Shefali called me on 11 May and told me her husband Umesh had been rushed to hospital with breathing difficulties, it was a shock. My first thought - as unreal as it seemed - was coronavirus.

His death, five days later, showed us just how much India's healthcare system is being ravaged by the virus.

While we battled to save Umesh, I was embarrassed I had to use my professional contacts - built up over 20 years as a journalist in this city - so many times to ask for simple things that should have been routine.

And despite our repeatedly asking, the hospital where his life ended has still not explained exactly how he died or responded to the BBC's questions about why the family was not told.

'Doctors said Umesh needed to be admitted'

Anand Surgical hospital, where Shefali had taken Umesh when he fell ill, is a famous private hospital in Ahmedabad, the capital of the western state of Gujarat. It had been designated a specialised Covid hospital by the municipal corporation just a few days earlier.

However, when I called them, they told me that they did not have an isolation room as yet. There were also no ventilators or even doctors who could treat suspected Covid patients.

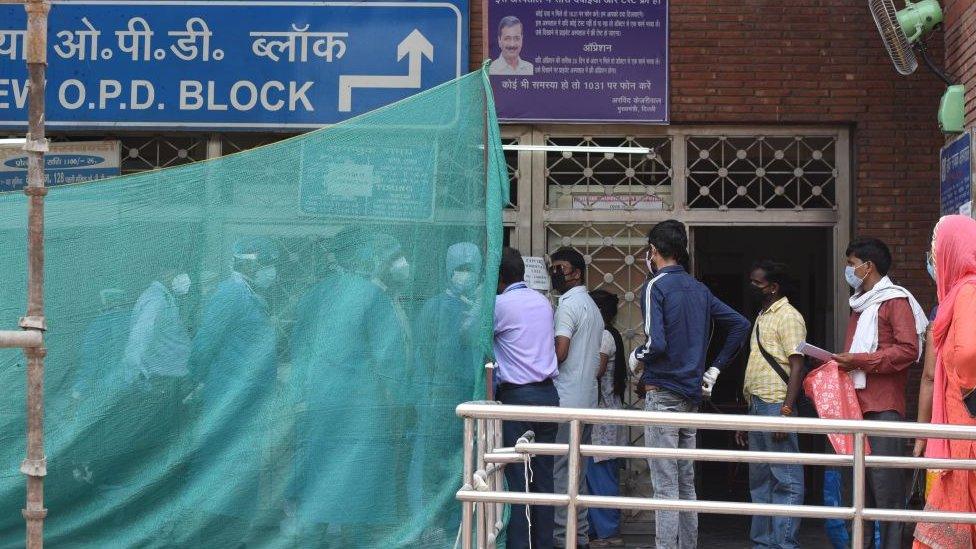

Hospitals across India say they are overwhelmed and are turning away patients

I told my sister to try taking him to a different hospital. But several private hospitals turned them away, saying they had no room.

Shefali finally managed to get a chest x-ray for Umesh at a nearby private hospital. The radiologist told the couple that he suspected Covid.

Umesh Tamaichi was 44 and a senior lawyer who practised at the Ahmedabad Metro court. My sister is the general manager of a reputed IT company. The couple lived in Chharanagar - a slum-like area of the city filled with small lanes, no civic facilities and haphazard construction.

Umesh and Shefali had dreams and worked hard to achieve them. They saved enough money to build their own house and send their two daughters to a good school - a rarity in a locality where spending money to educate girls is not the norm. One of them is about to sit pre-medical exams, while the other wants to be a lawyer like her father.

Umesh and Shefali worked hard to achieve their dreams for their family

A few days before Umesh started exhibiting symptoms, I had written a story on whether Gujarat was prepared for Covid-19. Several officials, including the state health commissioner, had talked about the state-run Ahmedabad Civil Hospital. They said it had several high quality ventilators, as well as trained staff.

So, I told Shefali to try taking Umesh there. I also called ahead to make sure they would see him. Doctors there looked at the x-ray and said Umesh needed to be admitted.

State-run hospitals have a terrible reputation in India for being overcrowded and understaffed. Many who use them complain of having to wait hours for treatment, as well as of a lack of space and basic hygiene, among other issues.

'Not a single bed in the city'

Afraid that Umesh would not get proper treatment, I approached the state health minister Nitinbhai Patel, who told doctors to ensure he got the best care.

The next afternoon, though, Umesh's condition deteriorated and he was shifted to critical care. I decided to try and move him to a private hospital. But as I called hospital after hospital, I was told there was no room. Not a single bed in the entire city.

In India some suspected coronavirus patients are turned away from hospitals

I tried everything. I called other journalists and even approached the mayor. But there was nothing anyone could do. So I focused on his treatment at the civil hospital - but his condition kept worsening.

Then I received a call from his doctor who said Umesh would have to be moved to a ventilator. During a video call, I was able to see him struggling for oxygen. He was unable to speak. All he could try to convey with his hands was that he was unable to breath.

A strong man, who exercised daily and had no health issues, Umesh could never have thought that a virus would land him in this situation. That instead of struggling to earn a bright future for his children, he would be struggling for a bit of air. He looked fragile and weak.

Meanwhile, Shefali, usually so strong, was breaking apart. With no-one able to visit, she was all alone with her two daughters, trying to comprehend the reality of what was happening to them.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

IMPACT: What the virus does to the body

RECOVERY: How long does it take?

LOCKDOWN: How can we lift restrictions?

ENDGAME: How do we get out of this mess?

She also knew she needed to be tested. She had both diabetes and high blood pressure - both dangerous co-morbidities for the virus. But this proved to be as difficult as getting a hospital bed for Umesh.

'She trusted me - I failed'

Repeatedly calling a government helpline got nowhere and while I also tried calling many officials, nothing worked. We even tried going to a private lab, but they wanted a doctor's prescription - which again proved difficult to get. When we finally managed to get one, the lab technician said that the government had ordered them to stop testing samples.

Eventually, with the help of a colleague, we managed to get Shefali tested on 15 May. The results, which came the next day, showed both Shefali and her younger daughter were positive. We decided to send her to a private hospital for treatment - again managed through a colleague. The next evening, I put her into an ambulance and followed in my car.

On the way, a relative called me and asked if I could check on Umesh's condition. I told him I had been trying to get information since morning, but no-one in the hospital had responded. He said he had received information that Umesh had died.

I was in shock - I did not know what to do. Given that I was following the ambulance, I couldn't even stop my car.

Umesh had never suffered serious illness before

I gathered up strength and called his doctor, who to my shock said he had no information as he was not on shift. I made a few other calls until one doctor finally confirmed that Umesh had indeed died - many hours earlier. But no-one had bothered to inform us.

The hospital did not respond to the BBC's questions about why the family was not informed.

Meanwhile, Shefali's ambulance reached the private hospital she was to be cared at, but I could not admit her as I knew she might want to go back and see her husband one last time - even if from a distance. I lied about an issue with the admission process and managed to get her back home.

Then came the most difficult task - breaking the news. Telling her the man who had loved her throughout his life, had breathed his last alone in a critical care unit while his body was left unattended for hours.

She screamed in anguish.

"You promised me Umesh would return home. Where is my Umesh now?"

As the number of Covid cases increase, the health system is buckling under the pressure

She had trusted me to bring her husband back to her. I had failed. The entire experience was eye-opening and humiliating.

I still don't know the circumstances around his death - what happened, did they try to save him at the end? How did his mobile phone, SIM card and watch disappear after his death? The hospital has not responded to these questions, when asked again by the BBC.

Ahmedabad is one of India's worst affected cities and as the cases surge, the number of hospital beds are decreasing.

And as the epidemic rages on, more people will find themselves stranded - denied access to basic healthcare. So many people have already died at home, turned away from every hospital. This might soon be the norm across the state.

If this was my experience, what is happening to the millions of others who do not have the levels of access I did?

- Published3 June 2020

- Published8 June 2020