Coronavirus: The hidden heroes of India’s Covid-19 wards

- Published

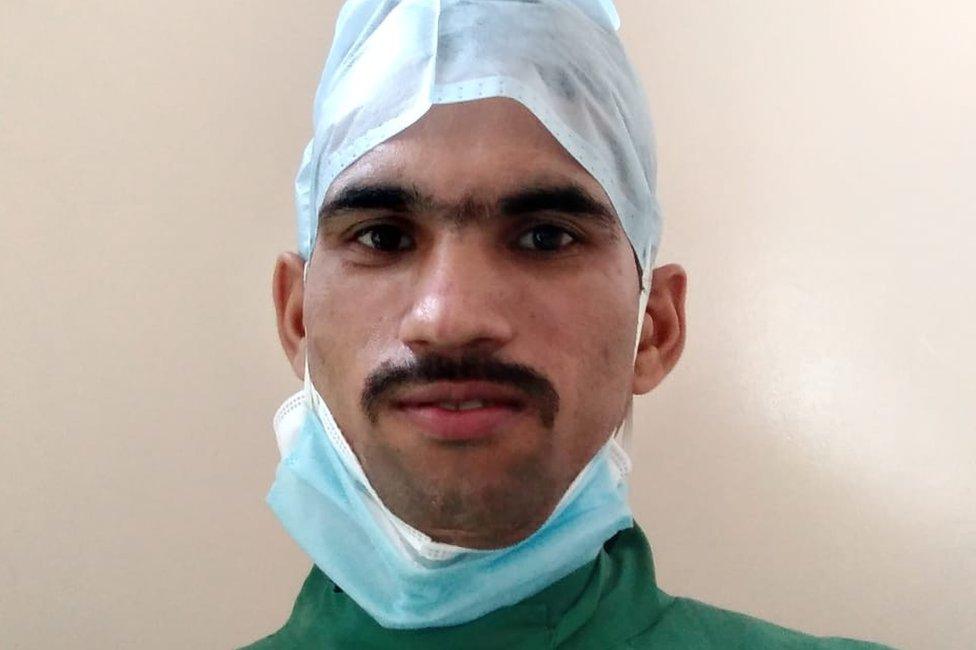

Hospital assistants - or ward boys, as they are known - play a crucial role in India

One morning in June, Deep Chand spotted a distraught family member of a Covid-19 patient standing outside the coronavirus ward in a hospital in India's capital, Delhi.

The man was desperately trying to speak to a doctor or nurse to find out about the condition of his relative who was a patient in the ward.

But it was a terrible day for doctors - some patients had died, a few others were critical, and new patients were being wheeled in throughout.

So Deep Chand, who worked as a ward boy - or assistant - walked up to the man and asked if he could help.

Ward boys care for patients throughout their stay

That man was me, and I was trying to find out how my brother-in-law was doing. It had been three days since he was put on a ventilator.

Doctors usually called every day to update us, but on that day no-one seemed to have time to do that.

When Deep Chand came up to me, I mistook him for a doctor because he was wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) and I threw a volley of questions at him.

"I am a ward boy and I can't help you with these questions," he said.

I must have sounded desperate and even rude, but he responded softly, without irritation.

He told me that my brother-in-law's blood oxygen level was fine, and there had been no turn for the worse in the last 10 hours.

They bring them food as part of their daily job

That's how I met Deep Chand, 28. Ward boys are nearly at the bottom of the hospital's hierarchy. They have no professional medical training, and their job is to assist doctors and nurses as well as help patients.

This includes everything from taking samples for testing, wheeling patients across the hospital for X-rays, serving them food, and sometimes just talking to them. And amid the painful chaos of the pandemic, these ward boys have become a source of support not just for patients but also for their families.

I will never forget my reassuring interaction with Deep Chand because it's just what I needed to hear while I waited for an hour outside the ward, anxious and scared. I could hear the sounds of the machines, patients yelling in pain and doctors and nurses shouting instructions at each other.

I also distinctly remember a patient pleading: "I can't breathe, please save me!"

Deep Chand's words cut through my panic and I ran to the car park to update my family - we nervously smiled at each other while standing at a safe distance.

This was the worst part - we couldn't hug or even hold hands when we desperately needed comfort. We had to maintain distance to protect each other. Not being able to hold each other - while my wife's brother was breathing through a machine - had become routine.

Even on a day the doctor told us "the next 12 hours are critical", we all broke down in our respective corners of the car park.

They talk to patients often to keep morale high

In the days that followed, we often relied on Deep Chand and his colleagues whenever doctors were too busy to give us updates.

We spent tense hours at home or in the hospital waiting for news from the ward.

It was difficult because the first two weeks of June saw a massive surge in Delhi's Covid-19 case numbers. Most hospitals were overrun, including the one where my brother-in-law was admitted.

In that chaos, ward boys like Deep Chand became messengers for dozens of families like ours.

I would often see them consoling families, supporting them and taking messages to those patients who were too ill even to talk on the phone.

One day when my brother-in-law's condition deteriorated, I was standing outside the ward and I broke down.

The doctor's update was factual. "We can't say anything at the moment, he is not improving."

But a ward boy walked up to me and said: "Don't worry, I have seen even severely ill patients recover."

His hopeful words gave me some relief.

They have to be in protective gear for hours

When doctors keep repeating "anything can happen", the mind takes you to dark places. It made me doubt everything.

Did we pick the right hospital? Should we have listened to him instead of convincing him to go on the ventilator? It had been a tough call - he had been against it, and the doctors kept saying there wasn't much time left to waste.

My family kept crying but praying for the "miracle" Deep Chand had told us was possible.

It was one of the most difficult times in my life, and Deep Chand's kind, calming words meant a lot to me - especially when I wasn't able to speak to the doctors.

Deep Chand has been working as a ward boy for five years

Speaking to me on the phone now, more than a month later, he says he felt the pain of the families but there was little that the doctors and nurses could do to improve communication.

"They were so busy, they somehow managed to speak to the families of serious patients once a day. It's nobody's fault - none of us were prepared for this kind of rush," he says.

Instead, it was Deep Chand and other ward boys who would share what information they could about the patient's progress - they routinely informed me about my brother-in-law's blood oxygen level.

"I can see the oxygen saturation level on the monitor and I don't mind sharing that information with families," Deep Chand says.

And this is me on a day when news from the ward wasn't promising

I also saw Deep Chand take food and letters for patients from their families.

He says he has been working as a ward boy for five years, but Covid-19 has completely changed the way he works.

He adds that being in protective equipment for 10-12 hours is painful, but it's nothing "compared to what patients and their families go through".

His colleague, Amit Kumar, nods in agreement, while speaking to me outside the Covid-19 ward one day. He says that even a little information goes a long way in reassuring families.

"Sometimes the families feel happy with little things - like when we tell them that the patient ate properly today or he smiled in the morning."

Ward boys also help discard used PPE suits

Every day, ward boys risk their lives in hospitals across the country. Hundreds of them have been infected with the virus. Some have even died. But their contribution in the fight against Covid-19 is seldom mentioned.

The ward boys I spoke to say this doesn't bother them. Deep Chand says he is not looking for special recognition.

When he was told that he would have to work in the "corona ward" at the start of the outbreak in March, he admits was concerned. "I was terrified for my safety and that of my family."

But then, he adds, he realised that he would not think twice before going into the ward if one of his family members was sick.

"Every patient is somebody's family."

That thought drove him to start working in the ward in April, and since then he has never considered quitting.

And doctors appreciate this. "Ward boys are an important part of any ICU unit," says Dr Sushila Kataria, the director of intensive care at Medanta Hospital.

"They watch our backs, they deal with discarded PPE kits and contagious samples. No doctor can work without their help," she says.

"They are also heroes in this fight like doctors and nurses."

They also help in bringing sick patients inside the hospital

But they are some of the lowest-paid employees in a hospital. The situation is worse in smaller towns where they are hired by contractors who lease their services to hospitals.

Sohan Lal works in a government-run hospital in the northern state of Bihar and earns 5,000 rupees ($66: £52) a month.

He says it's a paltry amount given the risk of working in a Covid-19 ward. "But I don't have any other job, so I will keep doing this. I also realise the importance of my job."

He adds that so many times he has given medicines to patients after consulting the doctor on the phone.

"Doctors seldom come for rounds more than once a day. So, patients rely on ward boys to convey their messages to the doctors."

They clean the wards as well

The other tough part of their job is seeing death so closely. Deep Chand says he feels distraught when a patient he has been caring for dies.

"Sometimes patients die after spending more than two weeks with us. They almost become like our family," he says.

But, he adds, he won't stop "until we defeat corona or it defeats me".

I wanted to specially thank him the day my brother-in-law was discharged after nearly a month in the hospital. But he disconnected my call, saying "he was on duty".

A text followed: "You don't need to thank us", he wrote. "Pray for us and all medical teams working in Covid-19 wards across the world".

And he had a message too: "Please wear masks and follow social distancing."

I can't agree with him more, having seen the worst of what this virus can do.

- Published27 July 2020

- Published25 April 2020

- Published20 May 2020