India’s economic woes may have only just begun

- Published

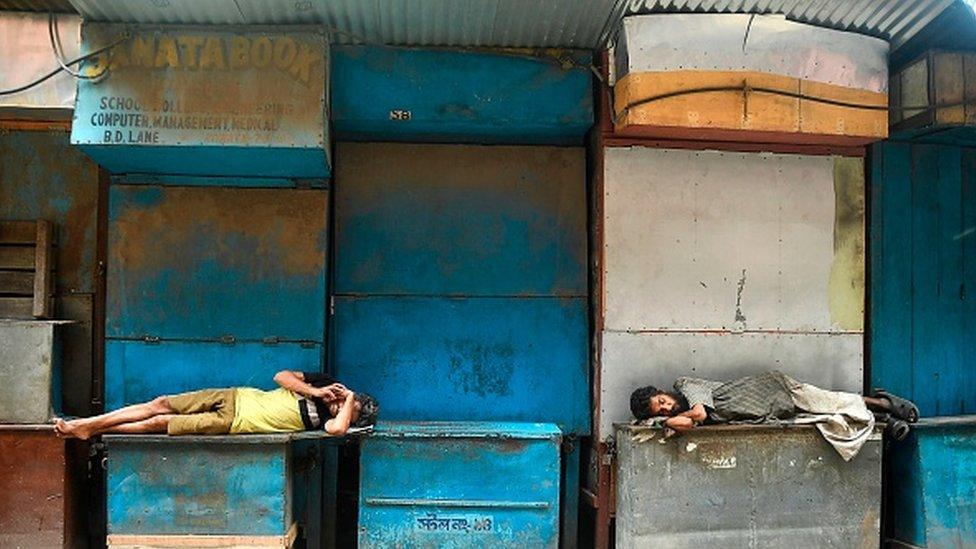

Small businesses have suffered the most during the lockdown

India's economy contracted by 23.9% in the three months to the end of June, making it the worst slump since 1996. A grinding lockdown brought on by the coronavirus pandemic has disrupted business and left millions out of jobs, reports the BBC's Nikhil Inamdar.

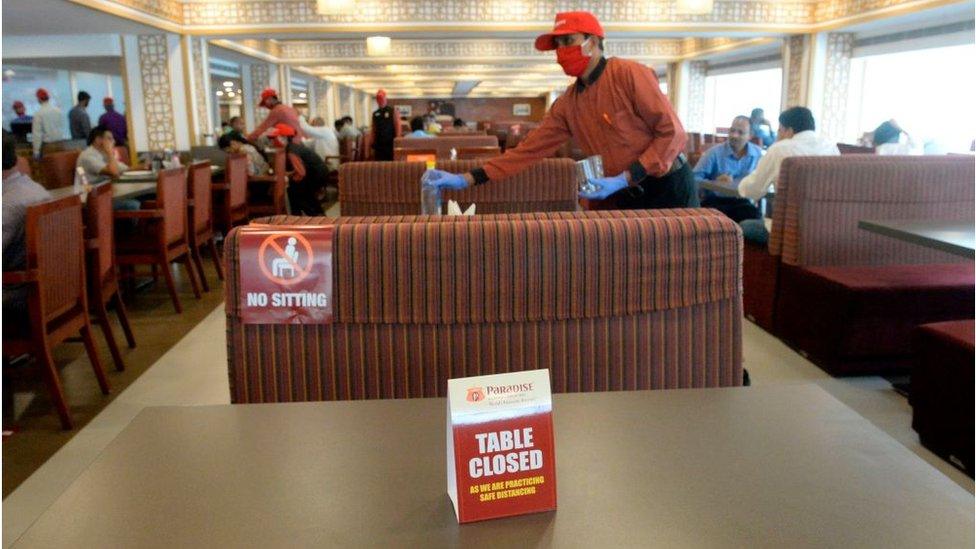

For the last five months, since India imposed one of the world's strictest lockdowns, Aditi Limaye Kamat's restaurant business has been bleeding money.

Her four popular eateries occupy prime real estate space across Dadar, an expensive neighbourhood in Mumbai, the country's financial capital.

"Only deliveries are being permitted. And that's not helping very much. It amounts to merely 10 to 15% of our overall business in normal circumstances and doesn't even cover salary as well as running costs," Ms Kamat told the BBC.

She wants the government to permit in-restaurant dining at the earliest with strict social distancing guidelines like in other parts of the world. "If not, many of us will be out of business by January," she adds.

India's National Restaurant Association has predicted that 40% of the country's restaurants will not survive the pandemic.

A fine print of the April to June GDP data released by the government on Monday reflects the pain of people like Ms Kamat.

Hotels and trade saw the sharpest contraction at 47% during the lockdown period, only preceded by construction activity which halved.

Barring agriculture, which posted modest growth of 3.4%, everything from mining to manufacturing and electricity to services contracted at alarming levels during this period.

"The time has come to unlock all the restrictions imposed in the lockdown phase at the earliest," Milan Thakkar, who runs a company that manufactures wall putty and plaster, said. His company, Walplast, saw sales plunge by a third during the lockdown and expects no incremental growth this year.

Calls from desperate Indian business owners to open up the economy are getting louder, despite India's coronavirus tally of 3.6 million cases, with nearly 80,000 new ones being reported every day.

One of the most severe lockdowns in the world has done little to curb the spread of the virus in India. What it has done is flatten the wrong curve, Rajiv Bajaj, the managing director of Bajaj Auto, one of India's largest manufacturers of auto rickshaws, said a few months ago.

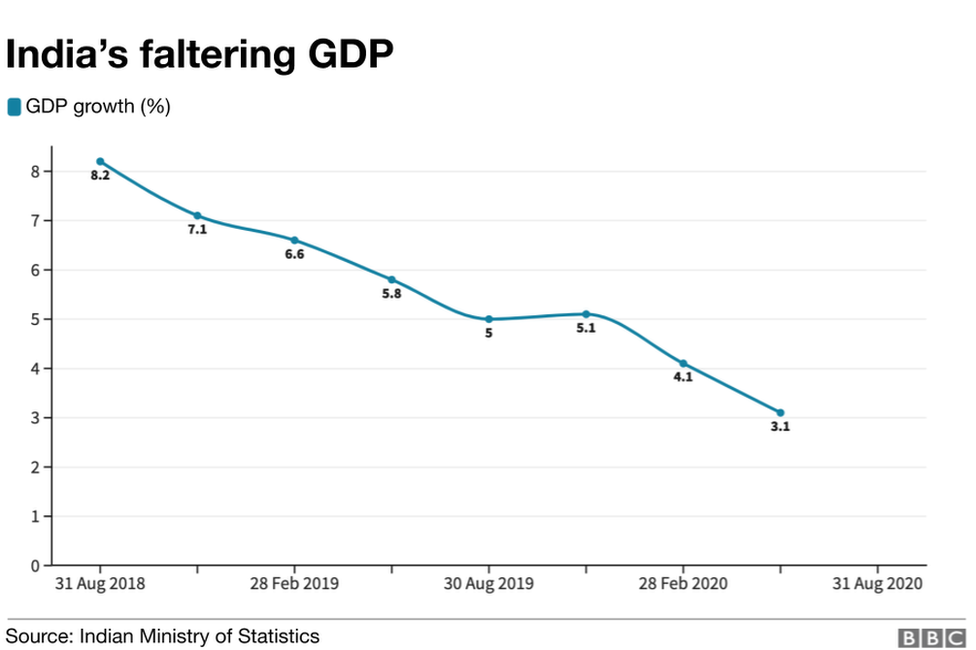

At -23.9%, India has become the fastest contracting large economy in the world, according to economist Vivek Kaul. And the likelihood is that this number will be further downward revised, given that the government's data collection was severely impaired during the lockdown.

"I suspect the revisions will be much larger," Pronab Sen, the former chief statistician of India, told the news site Bloomberg Quint.

All of this puts India firmly on the path to the deepest recession in its independent history. The country last contracted by -5.2% in 1979-80. The estimates for a contraction this year range between an optimistic -3% to a more realistic -10%.

Some 40% of the country's restaurants may not survive the pandemic

The implications of this for India's capacity to lift large swathes of its population out of poverty and generate employment for the youth are significant.

McKinsey Global Institute estimates that India will need to create at least 90 million non-farm jobs by 2030, if it is to absorb all the young workers that enter its labour market.

For a country that's lived through a decade of jobless growth and seen 19 million formal economy jobs vanish after the lockdown, this will take some doing.

India will have to clock a growth rate of at least 8 to 8.5% in the post Covid-19 scenario to achieve this goal, according to McKinsey. The global consultancy gives the country 12 to 18 months to act on a range of crucial structural reforms in areas such as healthcare and banking, take immediate steps to make its labour markets more flexible, improve social safety nets and ease the climate for doing business.

A failure to embark on this path could mean a decade of hardship, signs of which are already visible.

In the more immediate term, the government will need to focus on reversing the collapse in domestic demand and private consumption - which determines 60% of GDP - through more aggressive fiscal and monetary response to get the economy back on track.

"If left unaddressed, a longer period of below-normal activity risks knock-on effects on the labour market and ultimately on the banking system," warns analyst Sonal Verma. She expects India's central bank to reduce interest rates by at least another half a percent, starting in December.

At under 1% of GDP, India's stimulus measures so far have been among the most stingy among the world's major economies.

'Where will the poor like us go?'

The government has argued that it didn't see the point in pressing both the brake and the accelerator at the same time. But with a gradual unlocking of the restrictions, there are hints that a second stimulus package is being prepared.

Sanjeev Sanyal, principal economic adviser to the finance ministry, told local media recently that India was prepared to build infrastructure at an "unprecedented" scale as well as allow a several percentage points rise in its debt-to-GDP ratio to get back on the growth path.

But economists warn that with revenues plunging, tax receipts drying up and a fiscal deficit already expected to shoot up four percentage points above the expected levels, the leeway for India to spend its way out of the crisis remains limited at best.

And ultimately, a recovery in the economy will hinge on a recovery in the pandemic curve, which in India's case is yet to peak, according to some experts.

How expediently the Narendra Modi-led government gets that under control will play a significant role in determining India's economic fate.

- Published31 August 2020