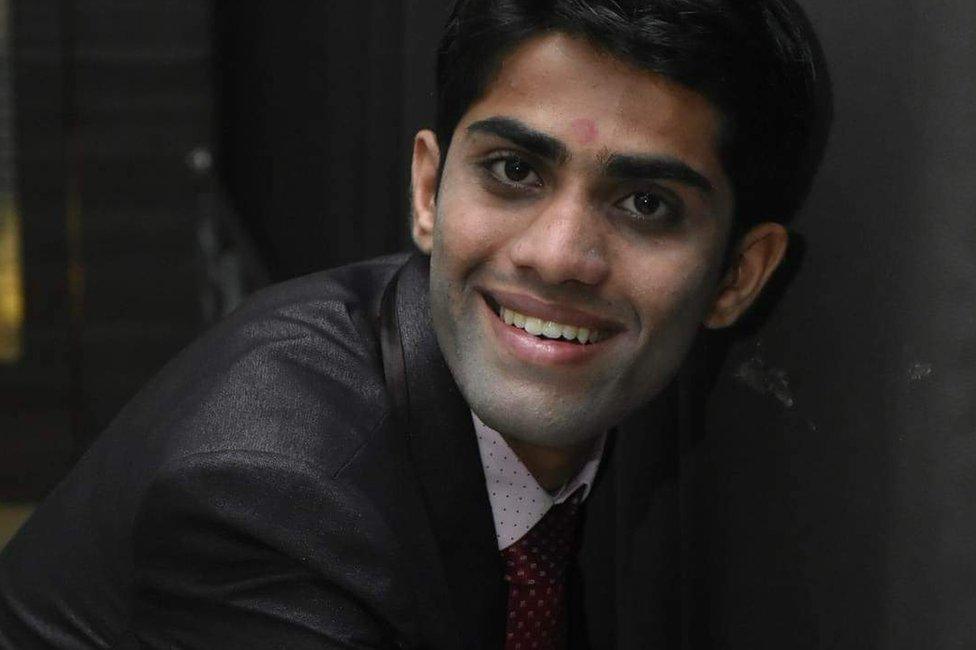

PMC Bank collapse: 'We lost our money and then our son'

- Published

Raunak Modi was saving up to start a business

When India's Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative Bank (PMC) went under in 2019, nearly a million depositors were cut off from their life's savings. One year later, many are still waiting for their money, reports the BBC's Nidhi Rai.

On 20 September, 2019, Raunak Modi deposited all his money - and that of his family's - in an account they held in PMC bank.

The bank was offering higher interest rates on fixed deposits, which is a popular saving instrument.

The money he deposited in PMC bank also included a large amount he got after selling his house in Mumbai. Raunak, 24, was planning to set up a business to secure a bright future for his wife and his child.

But three days later, his life turned upside down. He was home, watching the news when he learnt that India's central bank had frozen PMC's accounts - the bank's managers had allegedly committed fraud by hiding a pile of bad loans, amounting to about 65bn rupees ($880m).

He rushed to the bank and joined hundreds of other depositors who had begun gathering outside PMC bank's branches across the country to withdraw money. A year on, the bank's depositors - more than 900,000 people from middle and working-class families - are still waiting for their money to be returned.

Raunak was one of them. He killed himself earlier this month.

'I didn't know it was eating him up inside'

"Every morning he used to say, I think something good will happen. He had so much faith in the system," says Rajendra Modi, Raunak's father.

But, Mr Modi says, he watched his son lose hope as the months wore on. He was laid off in April because of the pandemic and soon after his marriage ended. Raunak, however, kept trying to get the money back from the bank.

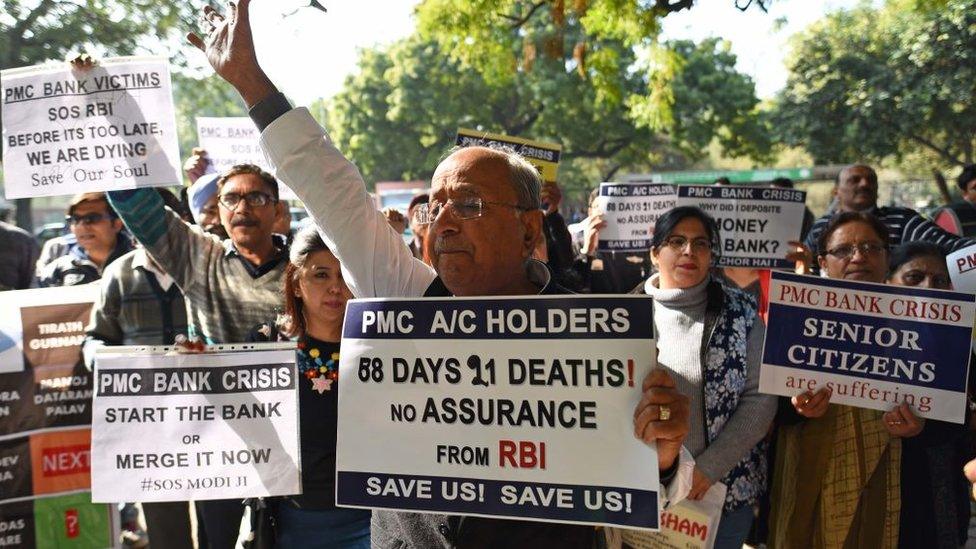

Depositors have been protesting against the bank for months

He was part of three WhatsApp groups, each with hundreds of PMC depositors who would share information and advice.

They protested, petitioned the courts, tweeted and wrote letters to officials and political leaders. Some are as young as Raunak, just starting out when a curveball struck; others are in their 60s, anxious that the comfortable retirement they had saved up for might no longer be an option; and there are those in their 80s, too shocked and exhausted to think of an alternative.

Raunak's family says they knew he felt helpless and anxious about the money, but they did not realise "how much it was eating him up from inside".

"We have lost everything. Our money's gone and now, so has our son," Mr Modi says.

Many other families who lost money say they have suffered too.

Kuldeep Kaur Vig, 64, had a stroke on hearing the news, according to her family. Murlidhar Dharra, 83, died because his family couldn't arrange funds for his heart surgery and Andrew Lobo, 74, died because he could not afford medical treatment. In November, 51-year-old Sanjay Gulati died from a heart attack after attending a protest by depositors.

What happened at PMC?

Founded in 1984, the bank has more than a 100 branches across India. It's one of some 1,540 co-operative banks that hold close to 11% of India's bank deposits - about $68bn. Co-operative banks are popular because they lend at lower interest rates, and often give higher interest than other banks.

'My daughter can't study because my bank took my money'

But the collapse of PMC bank exposed a harsh reality - poor regulation allowed the bank to flout rules for years.

The bank is accused of lending money to a real estate company - Housing Development & Infrastructure Ltd (HDIL) - through dummy accounts in the name of dead clients. When the company started to default on payments, the bank's management allegedly covered it up by under-reporting the extent of their exposure.

Depositors rushed to PMC branches to withdraw money when news broke

HDIL, which accounted for nearly 75% of PMC's loans, was the bank's single biggest borrower. But RBI rules permit a single group to borrow no more than 15% from a bank.

As the debt grew, the bank was forced to report the problem to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country's central bank. With no collateral from the cash-strapped HDIL to fall back on, the RBI initally limited withdrawals to as little as $13 per person to prevent depositors from withdrawing large sums in a rush. The RBI gradually increased the limit - it now stands at $1,350.

India's Enforcement Directorate, which looks into financial crimes, is investigating the bank for forgery and money laundering. The RBI too has filed a case against it for cheating and criminal conspiracy.

Too little, too late

The RBI has now increased its supervisory powers over co-operative banks, but depositors say all this is too little too late.

"We are borrowing from our relatives and friends to run our households. I have not paid the maintenance bill of the building where I live for the last six months", says 60-year-old Anita Lohia. She and her husband, both retired from jobs, have four accounts in a single branch of PMC bank in Mumbai.

"The system has failed us," she adds. "We are senior citizens. We have medicines to buy and regular medical check-ups to undergo. Who is going to pay for all that?".

She says they have been trying to meet officials but they have had no luck. "We are not beggars. It is our money that is stuck in the bank."

Anita Lohia, a retired school teacher, lost her savings in the bank collapse

Depositors are also confused and furious. "Why did they let it function if it was not safe? What was the RBI doing?" 60-year-old Kalyani Sheikh asks.

In 2016, India passed a law that puts more pressure on banks to identify and report troubled loans. But the banking crisis continues. This year alone, the RBI put 44 co-operative banks under lending or withdrawal restrictions for financial irregularities.

The RBI has said that PMC bank's recovery will take a long time, and that it was in such a bad state that no investor is ready to help.

Some experts agree - they say co-operative banks are risky at this time because they lend to borrowers who are more likely to default during a pandemic.

Business journalist Sucheta Dalal says there's another reason.

"PMC depositors are not knocking on the right doors. The RBI can solve this issue by finding a buyer, but there is a lack of political will."

Information and support

If you or someone you know needs support for issues about emotional distress, these organisations may be able to help.

If you are in India and are feeling emotionally distressed, visit Aasra, external and Befrienders International, external for more information about support services.

- Published1 August 2020