Nirbhaya Fund: Where did millions set aside after Delhi gang rape go?

- Published

How much has changed for rape survivors since 2012?

In 2013 - the year after the Delhi gang rape - India launched the ambitious $113m Nirbhaya Fund, vowing to reduce violence against women. Hundreds of millions of dollars followed since but a major new report by the charity Oxfam India, external finds that the fund has not done its job. The BBC's Aparna Alluri and Shadab Nazmi report.

In 2017, Kavita (whose name and those of other survivors in this article have been changed) turned up at a police station in rural Orissa state to allege her father-in-law had raped her. But the police, she says, summoned her in-laws, lectured them and sent her home to her parents. No case was registered. The police said it was a "family affair".

Pinky, 42, arrived late one night at a police station in Uttar Pradesh state in 2019. She says she was visibly injured after a "bad beating" by her husband. Even so, police took hours to register her complaint. When she then fled to her home city of Lucknow, fearing for her life, she went to the police there too. But she says the officer "looked her up and down" and told her she was at fault before eventually registering her complaint.

Late last year, Priya, 18, went to a police station in Orissa, alleging that the man she had eloped with had raped her and then disappeared. She says the officer told her: "You didn't ask us before falling in love with him and now you have come to us for help." She claims she was then forced to change her complaint to say she was married to him and he had abandoned her - a different crime with a shorter prison term.

Anyone who works with survivors of domestic or sexual violence - from social workers to lawyers to policy wonks - will tell you these examples are depressingly common in India. And that the hundreds of millions of dollars in government money that were supposed to make them less so haven't achieved their aim.

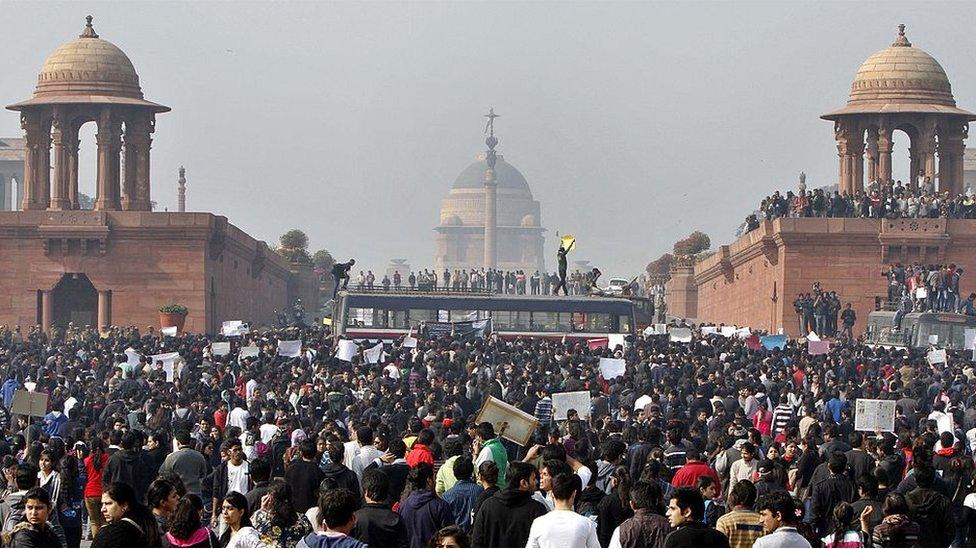

Protesters flooded the streets of Delhi in the wake of the 2012 gang rape

The Nirbhaya Fund is so named because of how the media referred to the young woman murdered in the 2012 Delhi gang rape. Indian law prohibits the identification of rape victims, so the media called her "nirbhaya", or fearless.

Her case, which sparked massive protests and headlines around the world, is seen as a watershed moment that led to new anti-rape laws and stricter guidelines for the medical examination and counselling of survivors of sexual violence in India. The fund was meant to kickstart changes that are long overdue.

But a new report by Oxfam India has found that red tape, underspend, obscure allocations and a lack of political will, external have undermined the Nirbhaya Fund, which was already up against a stubborn foe: patriarchy.

Here's why that has happened.

Women - and services - take second place

Most of the Nirbhaya Fund has gone to India's home ministry, which oversees police. But Amita Pitre of Oxfam India says the money has largely paid for programmes - improving emergency response services, upgrading forensic labs or expanding units fighting cyber crimes - that don't exclusively benefit women.

From railways to roads, money has been directed towards better lighting, more CCTV cameras, safer public transport and even a research grant to test panic buttons in vehicles.

"People want technology-based answers - but that won't help in 80% of cases where the accused are people known to women," Ms Pitre says.

These programmes are also heavily focused on physical resources, something that Nirbhaya's mother, Asha Devi, has criticised, external.

"The Nirbhaya Fund should have been used for women's security and empowerment but it is being used for works like road construction," she said in 2017.

Training officers in trauma-informed policing and investigation would be of more benefit to women like Kavita or Pinky, campaigners say.

Pinky, for instance, says she waited in the Lucknow police station for an hour-and-half while the inspector played badminton. When he finally agreed to talk to her, he told her: "This is between you and your husband. We only get involved if it's a stranger."

Asha Devi, whose daughter was killed in the 2012 Delhi gang rape, has criticised the use of the fund

It took Kavita more than three years to finally register a case against her father-in-law. The inspector who discouraged her from filing rape charges told her caseworker that since the accused was the father-in-law, it qualified as a domestic violence charge, not rape.

"I was so shocked I asked him how he had become an inspector without knowing the law," the caseworker recalls.

But changing attitudes is costlier and harder than buying CCTV cameras - and that partly explains why so much of the money has not even been used.

Underspend is a major problem

While the home ministry has spent most of the money given to it from the fund, other government departments and most state governments have largely sat on the cash.

The federal women and child development ministry, for instance, used only 20% of the money it had received up to 2019, accounting for about a quarter of the total Nirbhaya Fund spending since 2013. Its money went to set up crisis centres for rape or domestic violence survivors, shelters for women, female police volunteers and a women's helpline.

"It is not enough to launch a scheme," Ms Pitre says. "It is important to remove bottlenecks to expenditures and effective implementation."

This is where the fund has faltered most, campaigners say. While it's easy to set up centres and teams, sustaining them is much harder. Crisis centres exist in many places and do valuable work, but they often lack staff and money to pay for things from salaries to transport to unexpected charges - such as when a woman turns up in the middle of the night and might need a change of clothes if hers are torn or bloodied.

In Uttar Pradesh, public hospitals don't have enough rape kits or swabs or zip lock bags to collect and transport evidence, says Shubhangi Singh, a lawyer who counsels rape and domestic violence survivors.

By Oxfam's calculations, the Nirbhaya Fund is underfunded - it needs $1.3bn to allow even 60% of women dealing with any form of violence to be able to access services.

So why isn't the money being used up? "One reason is that they create hurdles, through say, daunting paperwork," says Reetika Kehra, an economist. "And there is no guarantee that even if the money is left over, it will roll over to the next year."

This uncertainty is also what could be stopping so many states from applying for or using the funds. They may be reluctant to commit to programmes whose future is uncertain, especially since the money is coming from the federal budget.

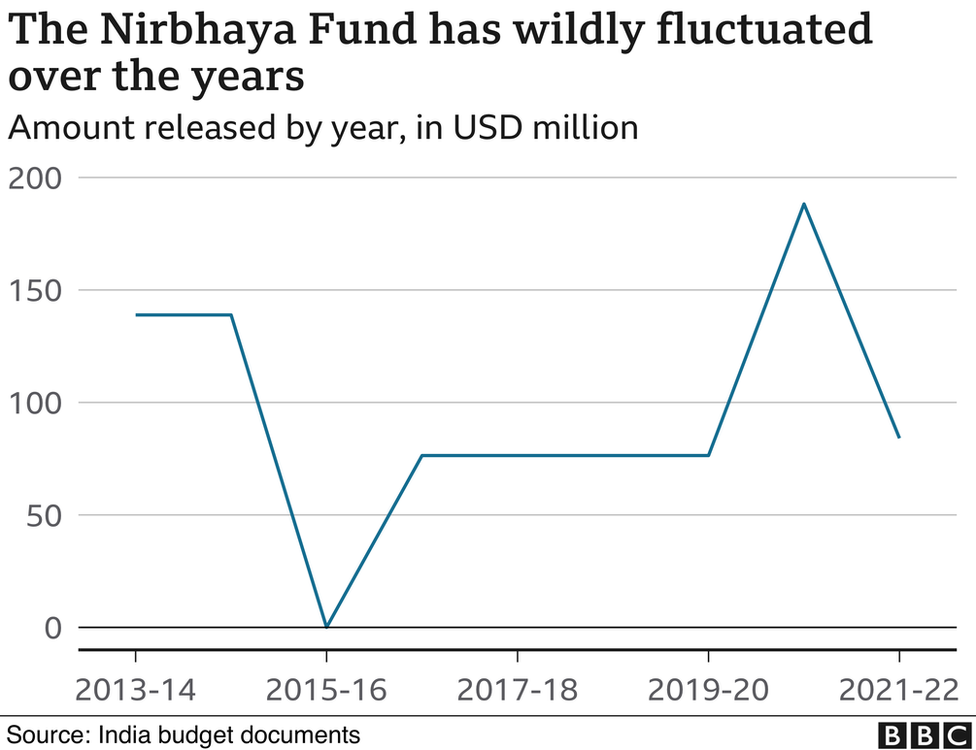

It's hard to say if the fund has been growing

It was endowed in 2013 with $113m (£82m) but has had something of a rollercoaster ride in the years since.

The money is split across schemes and categories whose names change each year so the easiest way to track the fund is to trace the amount that was actually released, and not what was allocated.

"Constantly rejigging these classifications is one way of projecting an increase. It becomes harder to compare like with like," Ms Khera says.

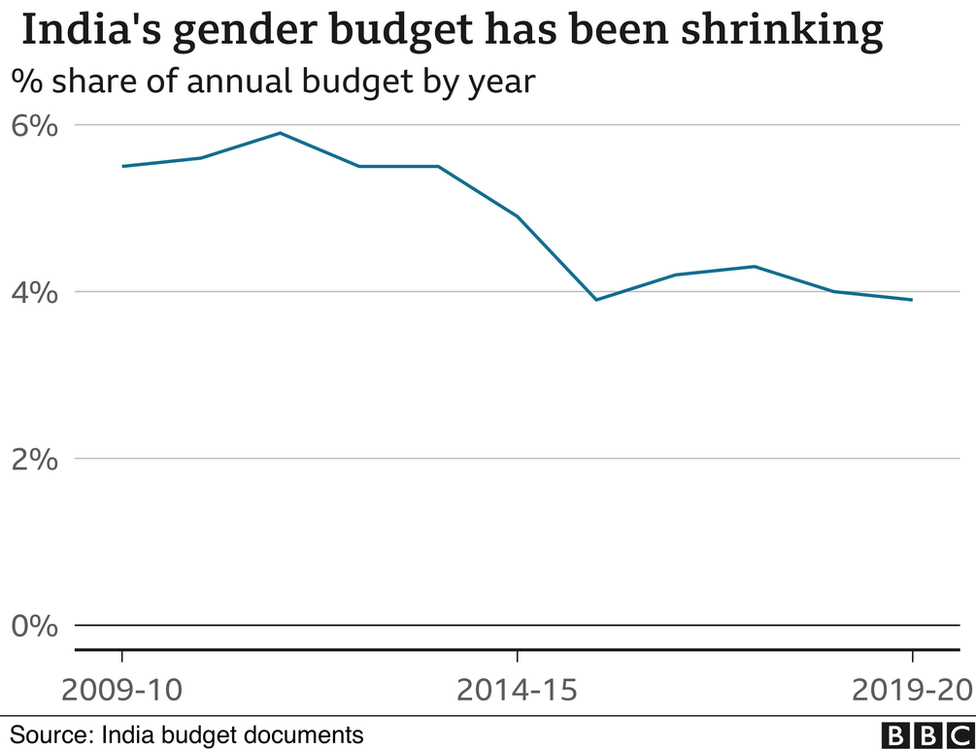

The Nirbhaya Fund is part of what the government calls a "gender budget" - money disbursed to programmes that benefit women. And the gender budget has been shrinking.

The gender budget follows the same pattern

More than a third of this year's $21.3bn gender budget went to Prime Minister Narendra Modi's flagship rural housing scheme - it helps the poor build homes, but a woman must be listed as owner or co-owner. The scheme has been a major beneficiary in the last two budgets as well.

While gender rights activists welcome the initiative, they are not so sure it's the best way to spend money from an already underfunded part of the pie.

"Most economics is a political calculation. In some states women vote more than men," says economist Vivek Kaul.

Also among the list of beneficiaries is a scheme to help rural women buy cooking gas (hence, the petroleum ministry received money from the Nirbhaya Fund) and a host of agriculture measures.

What about rights?

Since the fatal Delhi gang rape there has been no sign of crimes against women and girls abating in India, and justice remains out of reach for most.

A series of rape cases since 2012 have made global headlines for botched investigations, which in turn stymie prosecutions. And if the woman is poor - or from a tribe or at the bottom of India's unforgiving caste hierarchy - the odds against her are stacked even higher.

"If there is something worse than corruption, it is callousness," says Vikram Singh, a former director general of police in Uttar Pradesh. "We have not been able to recruit women prosecutors, police officers, judges and get our fast track courts in place. It's tardy utilisation of the Nirbhaya Fund."

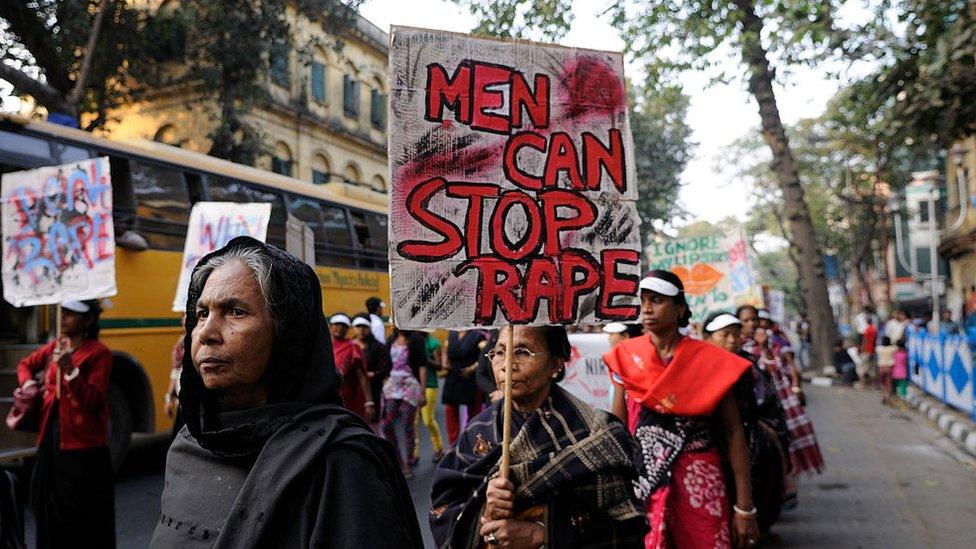

Protests are still held on the anniversary of the 2012 gang rape

He says there is a "cult of masculinity" that goes all the way down to police constables and cannot be dismantled without serious reforms and accountability - such as an independent authority to investigate complaints against police officers.

The apathy and casual misogyny extends beyond the police to doctors and even judges.

There has, however, been no money set aside to train doctors, although doctors play a key role in rape investigations and it's easier for women suffering domestic abuse to reach out to a doctor than a police officer. Education also appears low on the list of priorities but campaigners say it's crucial to change the way young boys think before they become men.

But gender rights advocates say funding is only one part of the challenge. The other is the continued emphasis on protecting women's honour rather than empowering them to exercise their rights.

They point to a growing body of research that shows certainty of conviction rather than severity of punishment is the biggest deterrence against crime. And that will only happen if a woman can walk into a police station and register a complaint.

"You need someone to drive that process," Ms Khera says. "There are ways to kill a programme while appearing to put all your weight behind it."

Related topics

- Published10 October 2020