Hathras case: A woman repeatedly reported rape. Why are police denying it?

- Published

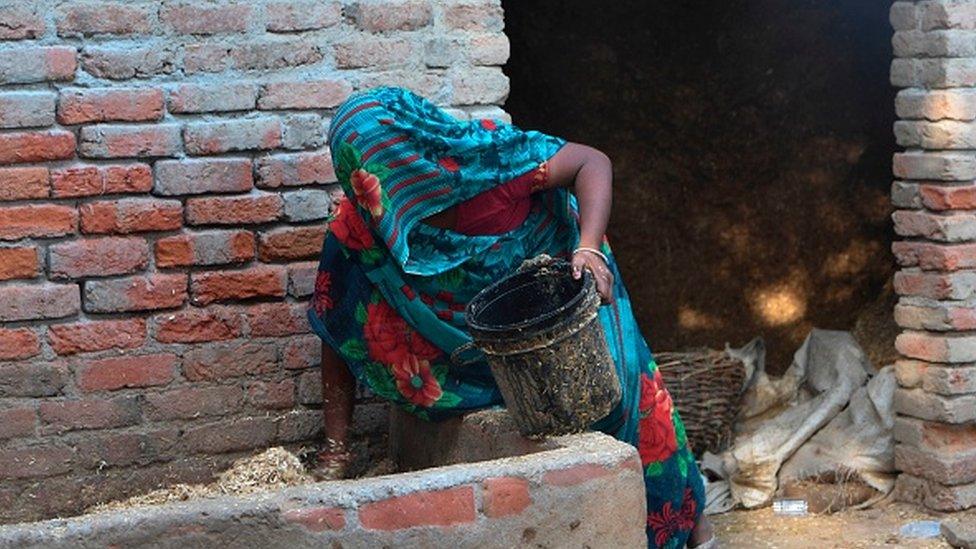

The woman was found by her mother (pictured) after the two had gone to cut grass

Late last month, a 19-year-old woman died in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh after reporting she'd been gang raped and and brutally assaulted. The evidence backs up her story, so why do officials keep insisting she wasn't raped? The BBC's Geeta Pandey reports from Hathras.

The injured teenager was brought to the Chandpa police station in Hathras district by her parents and her brother. In a 48-second video filmed at the scene and shown to the BBC, she can be seen lying on a cement platform while she is questioned by a policeman off camera.

There appear to be bruises on her neck, face and hand, and she seems to be in tremendous pain. She speaks with difficulty because, it would later emerge, she has a big gash on her tongue.

She tells the policeman her attacker tried to strangle her and the policeman asks her why. "Because I wasn't letting him do zabardasti," she says.

Zabardasti is an Urdu word that literally translates into "coercion" or "force" and is used by women especially in parts of rural India as slang for rape.

"Women who are not gender sensitised or bold enough to use the word rape often call it 'ganda kaam' [dirty work] or zabardasti," said Shabnam Hashmi, a women's rights activist who visited the family earlier this week.

The 19-year-old is seen repeating the same sentence in a second video that was recorded just hours later, when she was taken to the district hospital in Hathras. In the second video, she even names an upper-caste neighbour as the perpetrator.

The victim was a Dalit - men and women formerly known as "untouchables" who languish at the bottom of India's harsh caste hierarchy. On average 10 Dalit women were raped every day in India last year, according to official figures, and Uttar Pradesh has the highest number of cases of violence against women of any state.

The millet field - the scene of the crime

The young woman in Hathras - who cannot be named - was found in a field of tall millet crops by her mother. They had gone to cut grass for cattle fodder.

"She was lying on the ground, battered and bruised, barely conscious and naked from the waist downwards," her mother told me at her home in Bhulgarhi village in Hathras, sobbing into her veil. "She was bleeding, she couldn't move her neck, her arms and legs were lifeless, she was vomiting blood."

But neither of the young woman's two allegations of rape, made within hours of being attacked, were entered into police records.

"There were very serious lapses on the part of the police," said SR Darapuri, a former police officer and now vice-president of the People's Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) in Uttar Pradesh.

"The police did not write a complaint - they instead asked her brother to do it. They did not include what the victim told them. They didn't even call an ambulance to take her to hospital, even though she was in a precarious condition," he said.

The state government has suspended Hathras superintendent of police Vikrant Vir for "negligence and lax supervision". Four other policemen, including the one who is heard on the video interviewing the victim at Chandpa police station, were also suspended. Superintendent Vir denied any any wrongdoing.

For two weeks, the 19-year-old fought for her life. But on the morning of 29 September she died in the Delhi hospital to which she had been transferred, from injuries sustained during the attack. Her autopsy report has not been released.

The case made headlines only after police and administration officials cremated her body in the middle of the night on 29 September - a move the family say was made without their consent and which has raised suspicion.

Since her death, the state government has insisted that she was not raped at all. In a series of off-the-record conversations, officials tried to deny or downplay the rape allegation. And reports in the Indian press, external said the state hired the services of a PR firm to press its denial.

A senior police official, Additional Director General Prashant Kumar, said last week that the woman's family had not mentioned rape in the initial complaint, and cited a forensic report which said no semen was found in her viscera sample - a claim rebutted by experts who point out that an absence of semen in this sample does not rule out rape.

Doctors at the Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College Hospital (JNMCH) in Aligarh, where she was treated for two weeks, pointed out that the forensic report was based on samples taken 11 days after the attack. Protocol says any evidence gathered beyond four days after a rape is useless.

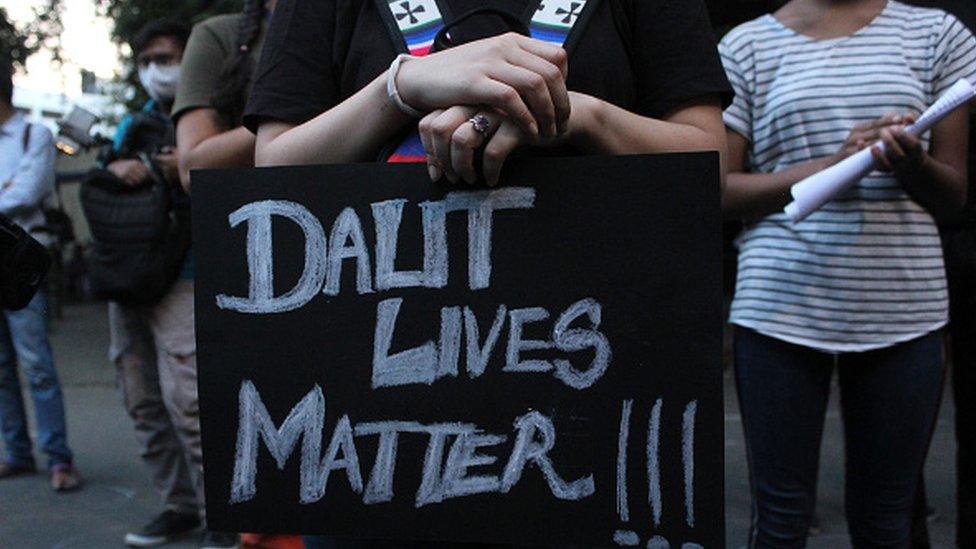

Protesters have called for Dalit rights after the assault

Police have since claimed that the young woman did not allege rape until 22 September, nine days after she was assaulted. But it is clear from the video footage that she says twice within hours of the attack "zabardasti" - another word for rape.

A report by the hospital's gynaecologist, who interviewed and examined the teenager, confirmed "use of force". I have seen a leaked copy of the report - it says she confirmed to the doctors that there had been "complete vaginal penetration with penis".

"On the basis of local examination, I am of the opinion that there are signs of use of force," the gynaecologist wrote. The report deferred confirming penetrative intercourse until a forensic report had been completed.

Then, there are the victim's own words. On 22 September, as her condition turned critical, the hospital called a magistrate and she made what is known as a "dying declaration".

These declarations carry weight in court. "Rapes happen at isolated places and there are rarely any witnesses so courts generally take a victim's dying declaration at face value," Mr Darapuri said. "It is generally enough for conviction, unless contradicted by other evidence."

According to a copy of the declaration submitted in court, and an interview with a health official who was present in the room, the 19-year-old told the magistrate she had been gang raped and strangled and she named four of her neighbours as the perpetrators. All four have since been arrested and all deny the allegation.

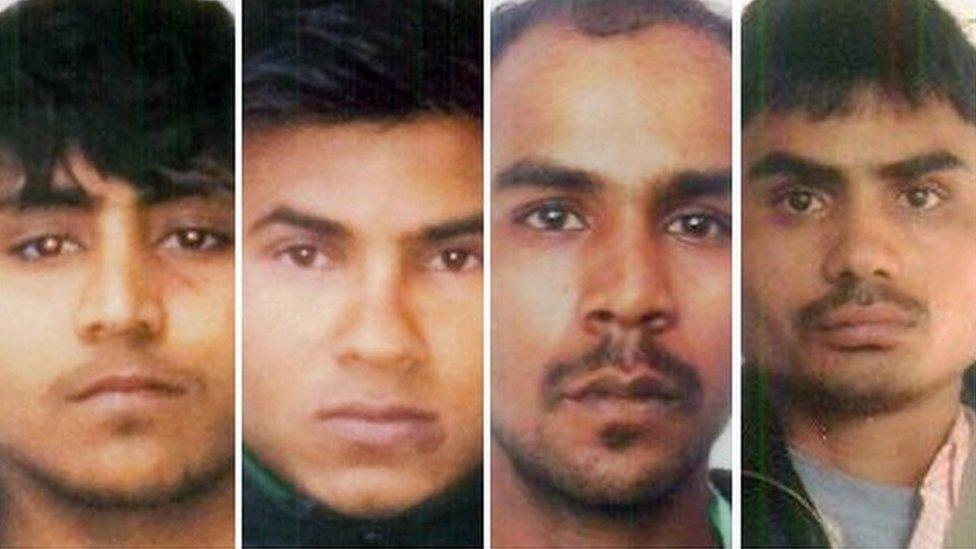

Large rallies have been held in support of the accused, attended by their relatives

In Hathras, only a narrow lane separates the houses of the victim and the accused. But their lives are divided by a caste hierarchy as rigid as it is old. She belonged to the Valmiki community, the lowest rung of the Hindu caste order; the four accused men are Thakurs, an upper-caste warrior community. The crime has only deepened the divide.

Under a tree behind their home, I found relatives of some of the arrested men. "We also want to know the truth," Sunder Pal, brother of one of the accused, said. "She should get justice. But my brother and other accused are also innocent and they should also get justice."

Hariom Kumar, brother of another accused, insisted his brother was away at his workplace at the time of the alleged attack.

Other Thakur men chipped in, accusing the victims's family of lying. "It's all rumour," said Kumar. "There was no rape."

It is not a surprise that the families of the accused would deny sexual assault. Laws passed in the aftermath of a vicious gang rape and murder of a young woman on a bus in Delhi in 2012 permit the death penalty for cases of rape with murder.

And state governments have potential political motivations to play down rape figures as well, said Mr Darapuri, the civil liberties activist and former police officer.

"Rape and atrocities against Dalits become political issues in elections so all governments try to keep these figures low," he said. "Village council elections and assembly elections are all due in the state in the next 18 months and the government does not want to give a handle to the opposition."

In the wake of the death of the young woman in Hathras, protesters flooded the streets. Police were heavily criticised for cracking down on the protesters. Many were beaten with sticks in an attempt to stop them from visiting the victim's family. Opposition leaders who had joined were shoved around.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, one of India's most controversial right-wing politicians, who is also a Thakur, is facing criticism for his government's handling of the case. Some of his party colleagues have held large rallies in support of the accused men, external attended by their relatives. Mr Adityanath, who has accused the opposition of "doing politics over the dead bodies of the poor", has not visited the victim's family.

On Tuesday, state authorities claimed to the Supreme Court that there was an "international plot" to cause caste and religious riots in Uttar Pradesh and topple Mr Adityanath's government.

The young woman's mother working at home earlier this week

Lost amid all the political din is the desperation and grief of a family in Hathras. At their home in Bhulgarhi village, well-meaning journalists ask the young woman's father to reply to allegations from the Thakurs that their daughter was in a consensual relationship with the main accused.

They ask him if he opposes the state's decision to hand over the investigation to the federal police; would he submit to a lie-detector test as being demanded by the accused; how much compensation has he received?

"I just want justice I don't want money," he told me. "I'm a daily-wage labourer. I earn 200 rupees [$3; £2] a day, I can live on 50 rupees. But I just want justice."

I asked her brother if he thought justice would come. "We have no faith any more," he said. "We'll believe it if it happens."

Read more on our coverage of the Hathras rape case:

Delhi Nirbhaya rape death penalty: How the case galvanised India

- Published8 October 2020

- Published20 March 2020

- Published9 September 2020