India Covid-19: Bollywood faces biggest box office test as cinemas open

- Published

A family in Delhi watch a movie after cinemas reopen

Cinemas have reopened in India after a seven month-long break forced by Covid-19. But with barely any new films being made and the pandemic still raging, lockdown losses will haunt its comeback, reports the BBC's Krutika Pathi.

"Cinemas have got the brunt. We were the first to shut down and we will be the last to reopen," Alok Tandon, the CEO of multiplex chain Inox, told the BBC last month. Many of India's nearly 10,000 cinema halls closed in March, just as coronavirus cases had started to appear and even before the government imposed a lockdown.

India continues to reopen, despite having the second-highest caseload in the world.

On Thursday, just as film theatres in several states welcomed customers, India's health ministry confirmed 680 deaths in the last 24 hours, its lowest in nearly three months. Daily averages of case numbers have also dipped in recent weeks, but experts say any slowdown must be greeted with caution.

After a long summer with no movies on the big screen, opening up cinemas is largely a symbolic and "feel-good move", says Rakesh Jariwala, a media and entertainment analyst. "The thinking is hopeful - like the idiom goes, build a city and people will come," he adds.

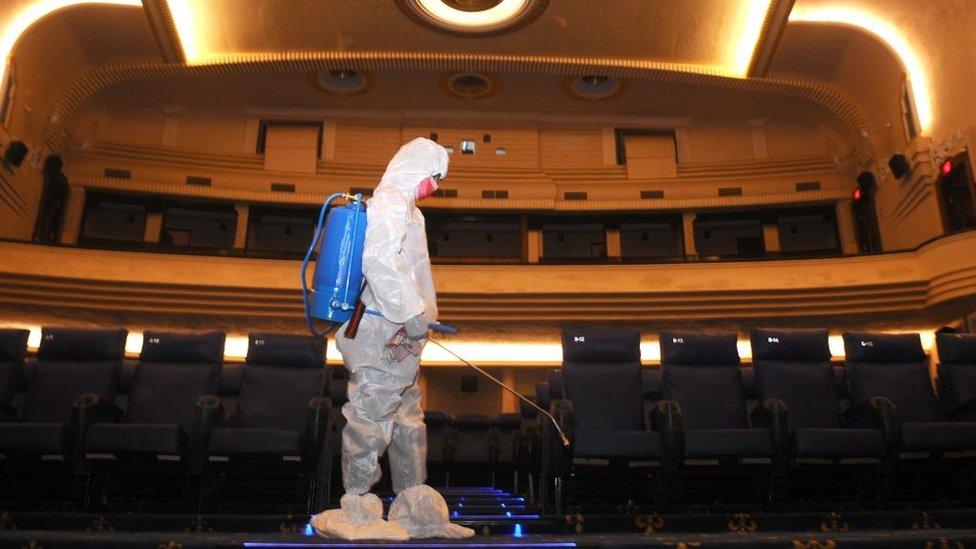

But watching a movie in a cinema won't be the same, at least in the foreseeable future. There will be no eager crowds or long queues at the ticket counter as social distancing is enforced. Names and phone numbers will be collected at the entrance for contact tracing. And no hall will run full as seating is capped at 50%. Even popcorn will be sterilised under UV rays for eight minutes, external, reported local media.

Cinema owners say they will follow every health and safety precaution

But the biggest blow is the lack of new material - for months, cinemas watched helplessly from the sidelines as streaming platforms snapped up Bollywood movies that were willing to opt for an online release. This leaves cinemas with no option but to re-release older titles, including those from 2018.

The problem, according to film critic Saibal Chatterjee, starts there. "People aren't dying to go back and watch old films - why would we spend our money and take a risk? Who would go with their family and potentially expose them?"

But studios remain reluctant to let go of new films just yet. "It's a vicious circle - people won't come unless a big blockbuster releases, but producers won't release a big movie unless people come," Komal Nahta, a film and trade analyst, says.

On Thursday, movie theatres in India struggled to attract customers with many running shows for small audiences, external, reported the Associated Press.

India's thriving south Indian film industry hasn't been spared either - releases of upcoming Tamil and Telugu films have been delayed after a halt in shooting.

A similar parallel can be drawn overseas too, where a popular American movie chain recently announced that it would temporarily close hundreds of locations, external in the US and UK due to a lack of blockbusters to screen.

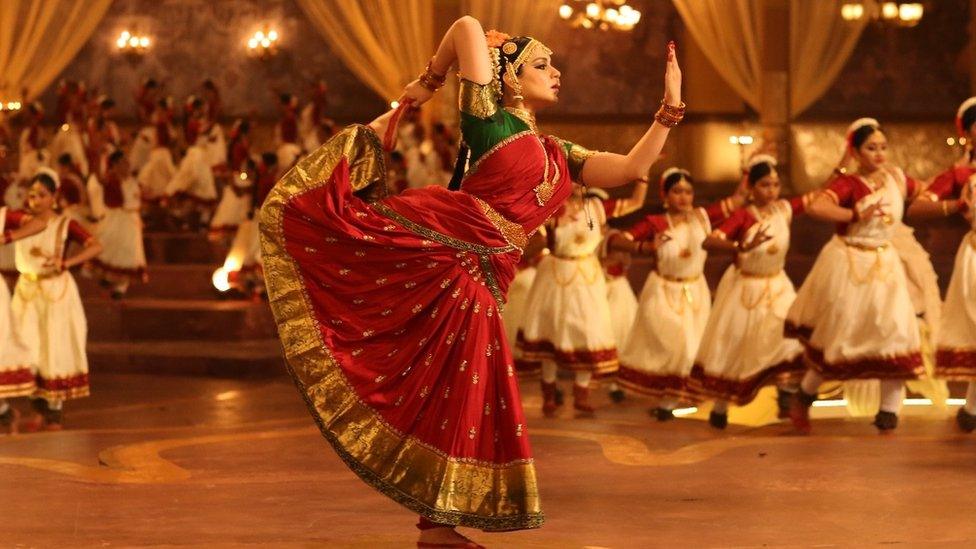

As of now, two big Bollywood extravaganzas have held out - Sooryavanshi, an action-packed police spectacle steered by superstar Akshay Kumar, is set to release in early 2021, while '83, a tribute to India's cricket World Cup victory in 1983, is due to have a Christmas showing. There are rumours that a sequel to a 2005 hit, Bunty Aur Babli, will release in mid-November, just in time for the Hindu festival of Diwali, often celebrated by both fireworks and a blockbuster.

The industry is banking on such releases to draw customers and ramp up sales. But it might not be enough to recoup their eye-watering losses - now pegged at around $1.2bn (£930m).

"It's going to be a very long-drawn process," adds Mr Nahta. "In the short term, they're only staring at losses."

Bollywood blockbuster Sooryavanshi is expected to release early next year

But first, cinemas have to rebuild confidence and dispel fears. "This is a dry run - there are no new movies but it's a chance to lay the groundwork, enforce all the measures and hope that cinemas don't see cases," says Mr Chatterjee.

Multiplex owners have said they will implement every precaution. But other public spaces that are back in action, such as restaurants or gyms, have seen low footfall.

Owners are hoping that India's reputation as a movie-obsessed country, one which sold just over a billion tickets in 2019, external and produces the most movies in the world, external, might help tide things over until new releases trickle in. And even though streaming is growing in popularity in India, experts say cinemas may do well in smaller cities and towns where streaming services are nascent and Covid-19 case numbers are fewer.

Even popcorn is reportedly going to be sterilised in some cinemas

"Movie-going runs in the blood of this nation," Vikram Malhotra, CEO of Abundantia Entertainment, says. "This is the classic Indian middle class activity - the day out with family."

But "from a purely epidemiologist's perspective, this is the wrong time to open," says virologist Dr Jacob John. Cinemas are at greater risk than other public spaces of becoming breeding grounds for the virus. "There's not much ventilation, the air is recycled by air conditioners and since it's dark, no-one will really check if everyone is wearing a mask," he adds.

Just because the doors have reopened, doesn't mean they can't close again, with experts fearing that even a single case within cinema halls could prompt a shutdown. "For the first time, the health of the film industry will not be governed by the content, but by the health of the public," says Mr Nahta.

- Published22 September 2020

- Published12 April 2020

- Published6 October 2020