India's first 'saviour sibling' cures brother of fatal illness

- Published

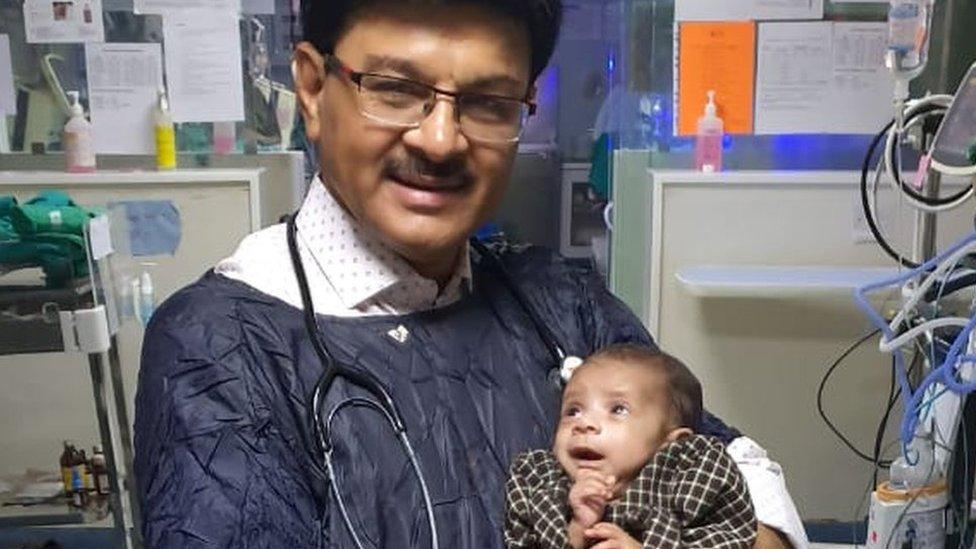

Kavya Solanki is India's first "saviour sibling"

The story of India's first "saviour sibling" has made national headlines. It has also raised questions about the ethics of using technology to create a child only to save or cure a sibling in a country with poor regulatory systems. The BBC's Geeta Pandey in Delhi reports.

Kavya Solanki was born in October 2018 and in March, when she was 18 months old, her bone marrow was extracted and transplanted into Abhijit, her seven-year-old brother.

Abhijit suffered from thalassaemia major, a disorder where his haemoglobin count was dangerously low and he required frequent blood transfusions.

"Every 20-22 days, he needed 350ml to 400ml blood. By the age of six, he'd had 80 transfusions," his father Sahdevsinh Solanki told me on the phone from their home in Ahmedabad, the largest city in the western state of Gujarat.

"Abhijit was born after my first daughter. We were a happy family. He was 10 months old when we learnt that he was thalassaemic. We were devastated. He was weak, his immune system was compromised and he often became ill.

"And when I found out that there was no cure for his illness, my grief doubled," Mr Solanki said.

To understand better what ailed his son, he began reading all the literature he could find on the disease, researching possible cures and sought advice from medical experts.

When he heard about bone marrow transplant as being a permanent cure, he began exploring it. But the family's bone marrow, including Abhijit's older sister's, wasn't a match.

In 2017, he came across an article on "saviour siblings" - a baby created for the purpose of donating organs, cells or bone marrow to an older sibling.

Abhijit suffered from thalassaemia major

His curiosity aroused, he approached Dr Manish Banker, one of India's best-known fertility specialists, and persuaded him to prepare a thalassaemia-free foetus for Abhijit's treatment.

Mr Solanki says they opted for a saviour sibling because they ran out of choice. One hospital told him that they had found a bone marrow tissue match in the US. But the cost was prohibitive - between 5m rupees ($68,000; £52,000) and 10m rupees - and since it was an unrelated donor, he was told the success rate would be 20-30%.

The technology used for Kavya's birth is called pre-implantation genetic diagnosis - it allows embryos to be screened for disease-causing genes and has been used in India for a few years now, but it's the first time it's been used to create a saviour sibling.

Dr Banker says it took him more than six months to create the embryo, screen it and match it with Abhijit's. Once they had the perfect match, the foetus was planted in the mother's womb.

"After Kavya's birth, we had to wait another 16 to 18 months so that her weight could increase to 10-12kg. The bone marrow transplant was done in March. Then we waited for a few months to see whether the recipient had accepted the transplant before announcing it," he told me.

"It's been seven months since the transplant and Abhijit has not needed another transfusion," Mr Solanki told me. "We had his blood sample tested recently, his haemoglobin count is over 11 now. The doctors say he's cured."

Dr Deepa Trivedi, who carried out the transplant, told BBC Gujarati's Arjun Parmar that after the procedure, Kavya's haemoglobin levels had dipped and there was localised pain for a few days from where the bone marrow was taken, but she's now fully healed.

"Both Kavya and Abhijit are now completely healthy," she said.

Mr Solanki says Kavya's arrival has transformed their life. "We love her even more than our other children. She's not just our child, she's also our family's saviour. We'll be grateful to her forever."

Mr Solanki says he loves Kavya "even more than his other two children"

Adam Nash - born in the US 20 years ago to be a donor for his six-year-old sister who suffered from Fanconi anaemia, a rare and fatal genetic disease - is considered the world's first saviour sibling.

At the time, many questioned, external whether the baby boy was really wanted or merely "created as a medical commodity" to save his sister? Many also wondered if it would lead to eugenics or "designer babies, external"?The debate was renewed in 2010 when Britain reported its first saviour sibling.

Kavya's birth has raised similar questions in India about babies becoming "commodities" and whether it's ethical to "purchase a perfect offspring".

"There's the long-standing ethical issue, as [German philosopher Immanuel] Kant said, that you should not use another person exclusively for your own benefit," says Prof John Evans, who teaches sociology at University of California and is an expert on the ethics of human gene editing.

Having a saviour sibling raises several questions, he says, and "the devil is in the detail".

"We have to look at the parents' motivation. Did you have this child only for this reason to create a perfect genetic match for your [sick] child? If you did, then you're putting at risk a child without their consent."

Then, he says, there's the issue of what the saviour sibling is going to be used for?

"One end of the spectrum is using cells taken from the umbilical cord of a baby, the other end is to take an organ. Taking bone marrow falls somewhere in the middle - it's not zero risk but it's not as damaging as removing an organ which would cause permanent damage to the donor," Prof Evans told me.

But the most important ethical question, he says, is where does it stop?

"It's a very slippery slope and it's very hard to put barriers on it. It's one thing to create a saviour sibling for bone marrow, but how do you stop there? How do you not go on to modifying genes in existing humans?"

Britain, he points out, has a rigorous regulatory system that is used to grant permission for genetic biotechnology "that stops them from leaping too far forward down the slope".

"But Indian regulatory systems are not that strong and this is like opening the Pandora's box," says journalist and writer Namita Bhandare.

India has more than 40 million people living with thalassaemia

"I don't want to judge the Solanki family," she says. "In a similar situation, as a parent I may have done the same.

"But what we need is a regulatory framework. At the very least, there's the need for a public debate, and not just with medical professionals but also child rights activists. This child has been conceived without any debate. How can something so important fly under the radar?" Ms Bhandare asks.

Mr Solanki, a Gujarat government officer, says it's "not proper" for outsiders to judge his family.

"We are the ones living this reality. You have to look at people's intentions behind an act. Put yourself in my situation before you judge me," he tells me.

"All parents want healthy children and there's nothing unethical about it to want to improve the health of your child. People have children for all sorts of reasons - to take on the family business or to continue the family name or even to provide company to an only child. Why scrutinise my motives?"

Dr Banker says if we are able to create babies who are disease free by using technology, why shouldn't we?

"The fundamental questions we need to look at in India are regulation and registries. But we can't deny use of technology because potentially someone would misuse it."

Screening has been used since the 1970s to identify babies at risk of Down's Syndrome and Dr Banker says gene-elimination is very similar to that - the "next step" - and the idea is to eliminate these disorders in the next generation.

He says what they have done for the Solankis involved "a one-time procedure with minimum risks" and the result, he says, justifies the means.

"Before this treatment, Abhijit's life expectancy was 25-30 years, now he's completely cured so he will have the normal life expectancy."

Read more from Geeta Pandey

- Published5 December 2019

- Published14 December 2018