Delhi's Covid cases spike as temperatures drop and pollution rises

- Published

Heavy pollution has shrouded the city in recent days

India's capital, Delhi, is battling a winter surge in Covid-19 cases as temperatures plummet and air pollution rises to dangerous levels.

The city confirmed more than 8,500 cases on Wednesday alone, its highest daily record yet.

It also added 85 deaths in a day, putting the total beyond 7,000.

The sharp spike in cases after a months-long lull has also put pressure on hospitals - more than half the available beds are already occupied.

Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal has written to the federal government asking for more beds at government hospitals as public pressure mounts.

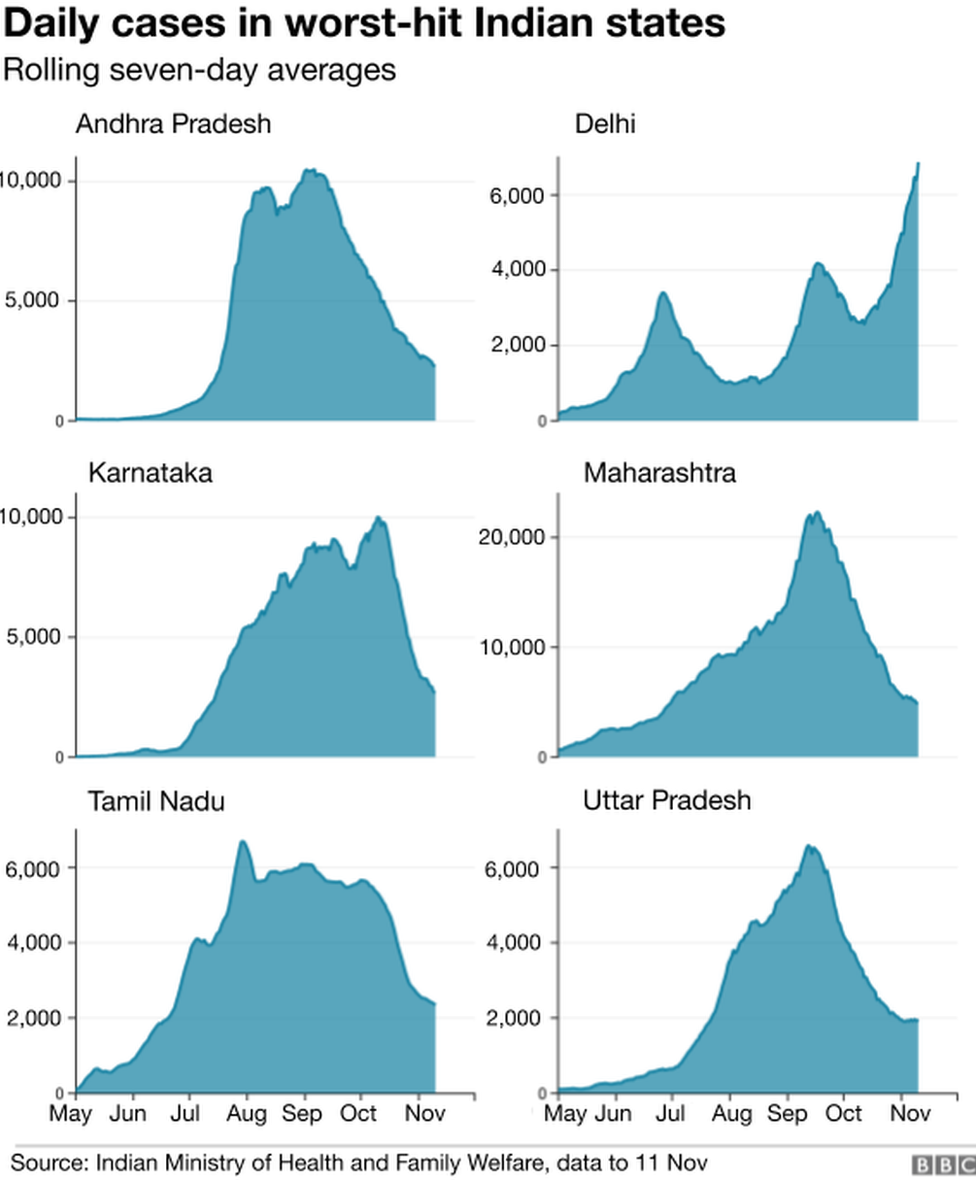

At 8.6m and counting, India currently has the world's second-highest caseload. But it had been on the decline from the middle of September: daily case counts dropped from nearly 100,000 to as low as 37,000 in the weeks that followed, even as testing remained consistent.

The daily national tally continues to hover between 40,000-50,000 - India recorded some 48,200 cases on Wednesday.

But Delhi has seen an alarming spike in recent weeks, recording more new cases than any other state. The capital has confirmed just over 450,000 cases so far, some 42,000 of which are active.

It comes as large swathes of northern India confront a winter season and dangerously high levels of air pollution - two factors that could significantly worsen efforts to control the virus, according to experts.

The rising numbers also coincide with a busy festival season in India, with Hindus celebrating Diwali this weekend. Delhi has banned the sale and use of fireworks and officials have reinforced the need for social distancing, but visuals of crowds thronging markets in the city have caused alarm. Authorities found a high positivity rate among shopkeepers, external in some of the oldest markets, which are at risk of becoming hotspots.

"Two elderly patients of mine had to wait for more than 20 hours to get a bed," said Dr Joyeeta Basu, a physician in Delhi.

Nearly 8,600 beds out of the 16,573 Covid beds in Delhi's public and private hospitals were full as of Wednesday evening, according to the government's Corona app. But more worryingly, unoccupied beds in intensive care units (ICU) are more scarce - only 176 beds with ventilators and 338 beds without ventilators are available. On Thursday, the Delhi High Court said some 33 private hospitals could reserve 80% of ICU beds for Covid patients, external due to spiralling cases and strained hospital resources.

Residents in Delhi have flocked to markets during the festive season

Doctors say the pandemic is raging inside the city's hospitals, where free beds are getting filled up by the minute.

Thousands of beds in the government-owned hospitals remain free, according to the app. But there are no vacant beds in at least 24 private hospitals and less than 50 are available across 80 private hospitals listed on the app.

But many who can afford private healthcare will not choose to go to a public hospital in India, where the quality of infrastructure is often poorer. India has an abysmal record in public health, spending just over 1% of its GDP on it.

"All of my patients would only go to a private hospital. But with the way things are going, we may have to settle for whatever beds we can get in the coming days," Dr Basu added.

Dr Randeep Guleria, director at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, one of India's biggest public hospitals, told local media that the spike means patients requiring admission into hospitals will rise.

"Additionally, there is an increase in the number of patients coming to the emergency [room] with acute respiratory problems because of air pollution and respiratory viral infections," he told NDTV.

Air quality monitors show that pollution levels are 14 times greater than the World Health Organization's (WHO) safe levels.

Another worrying factor is that general immunity in colder weather is reduced regardless of one's age or comorbidities, according to Prof K Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, a Delhi-based think tank.

Cold weather is also more hospitable to the virus, whose survival time rises in dry and chilly air, he said.

"Cold air is heavier and less mobile, which means viral clouds or viral particles will hover closer to the ground, making it easier to get into one's lungs."

Add pollution to this scenario, and it's "a double whammy", he added, as cooler air means that pollutants will stick around longer.

Studies around the world have linked air pollution to higher Covid-19 case numbers and deaths. A Harvard University study showed that an increase of only one microgram per cubic metre in PM 2.5 - dangerous tiny pollutants in the air - is associated with an 8% increase in the Covid-19 death rate.

How children in India's capital Delhi are affected by air pollution

Another study by Cambridge University found a link between the severity of Covid-19 infection and long-term exposure to air pollutants, including nitrogen oxides, car exhaust fumes or burning of fossil fuels.

"We have to keep our fingers crossed," said Prof Reddy, adding that Delhi initially felt a strain when cases shot up in April. "It started to come back down in June when we had warmer weather and much better air."

European countries like France and Italy, which grabbed headlines at the start of the pandemic for rising cases, were hit hard in January and February under a harsh winter, he said.

"This is the first time we will have to deal with the virus under a winter season so we can't go by what happened in the summer. We will certainly be more vulnerable."

- Published20 October 2020