Coronavirus: Has the pandemic really peaked in India?

- Published

India has recorded some 7.5 million Covid-19 infections so far

Has the coronavirus pandemic already peaked in India? And can the spread of the virus be controlled by early next year?

A group of India's top scientists believe so. Their latest mathematical model, external suggests India passed its peak of reported infections in September and the pandemic can be controlled by February next year. All such models assume the obvious: people will wear masks, avoid large gatherings, maintain social distancing and wash hands.

India has recorded some 7.5 million Covid-19 cases and more than 114,000 deaths so far. It has a sixth of the world's population and a sixth of reported cases. However, India accounts for only 10% of the world's deaths from the virus. Its case fatality rate or CFR, which measures deaths among Covid-19 patients, is less than 2% - among the lowest in the world.

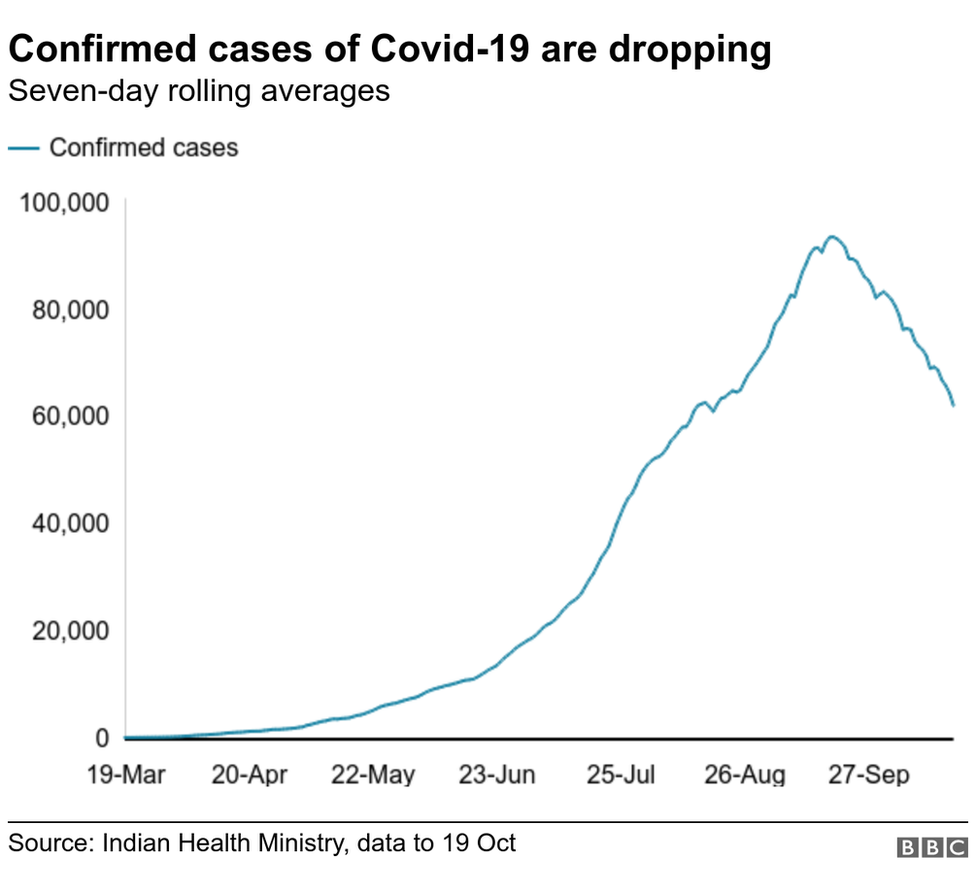

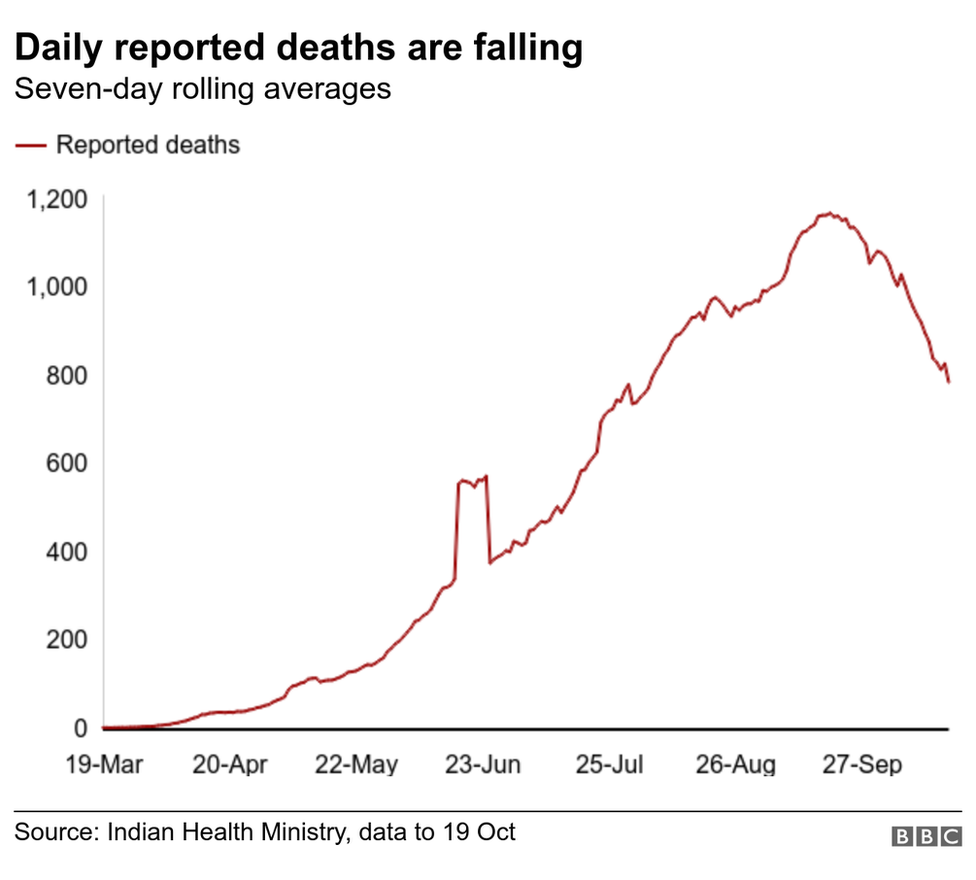

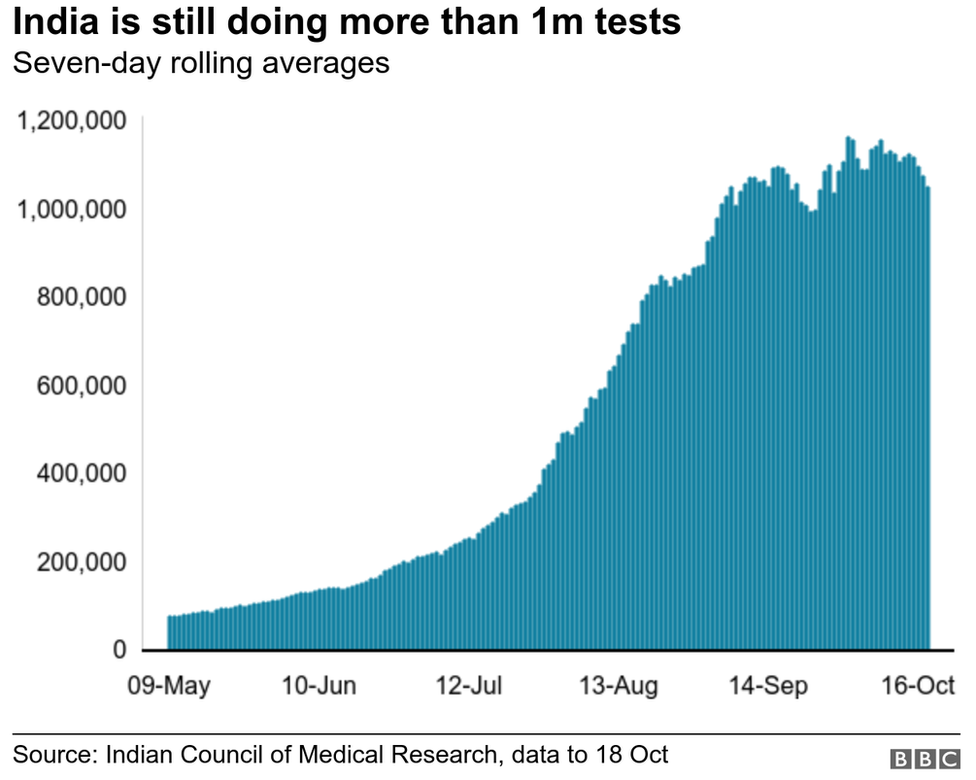

India hit a record peak in the middle of September when it reported more than a million active cases. Since then the caseload has been steadily declining. Last week, India reported an average of 62,000 cases and 784 deaths every day. Daily deaths have also been falling in most states. Testing has remained consistent - an average of more than a million samples were tested every day last week.

The seven scientists involved in the latest mathematical study commissioned by the government include Dr Gagandeep Kang, a microbiologist and the first Indian woman to be elected Fellow of the Royal Society of London. Among other things, the model looks at the rate at which people are getting infected, the rate at which they have recovered or died, and the fraction of infected people with significant symptoms. It also maps the trajectory of the disease by accounting for patients who have shown no signs of infection.

The scientists suggest that without the lockdown in late March, the number of active cases in India would have peaked at more than 14 million and that more than 2.6 million people would have died from Covid-19, some 23 times the current death toll. Interestingly, based on studies in the two states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, the scientists concluded that the impact of the unchecked return of out-of-work migrants from the cities to the villages after the lockdown had "minimal" impact on case numbers.

"The peak would have arrived by June. This would have resulted in overwhelming our hospitals and caused widespread panic. The lockdown did help in flattening the curve," Mathukumalli Vidyasagar, a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad, and also a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, who led the study, told me.

But India's busy festival season is around the corner. This is when families get together. So a few "superspreader" events and increased mobility could still change the course of the virus in two weeks. Kerala, for instance, recorded a sharp uptick in cases in September following celebrations of Onam, a harvest festival.

The scientists have warned of a massive spike in cases if people let their guard down: they predict a new peak of 2.6 million active infections by the end of October, up from 773,000 currently.

"All our projections will hold if people adhere to the safety protocols. We believe India went past the peak [of active infections] in September. We must not relax. There is a human tendency to think that the worst is behind us," Prof Vidyasagar says.

But most epidemiologists believe that another peak is inevitable and that northern India will likely see a rise in caseloads during a smog-filled winter that begins in November. They believe that the recent decline in cases and deaths is a promising sign, but it's far too early to say that the pandemic is receding.

Dr Bhramar Mukherjee, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of Michigan who has been closely tracking the pandemic, told me it "does look like India has gone through its first wave".

But she believes there could be a rise in deaths in the winter due to pollution, which is especially bad for respiratory diseases.

Meanwhile, she added, it was critical to keep doing antibody surveys and monitoring cities and villages where a low proportion of people have been infected as there was more room for the virus to spread.

"If the natural experiments across the world tell us anything, there will be another peak, when and how high is hard to tell. The key is to keep cases and hospitalisations lower than the hospital capacity at a given location and keep practicing the public health guidelines. Let us worship human health, life and dignity this autumn," Dr Mukherjee says.

Clearly, hope can be quickly extinguished by complacency. So keep your mask on, and avoid large gatherings.

Charts by Shadab Nazmi

Read more stories by Soutik Biswas

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

ENDGAME: When will life get back to normal?

EASY STEPS: What can I do?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- Published23 June 2020

- Published15 June 2020