India coronavirus: The tragedy of the tuk-tuk driver who fled Covid

- Published

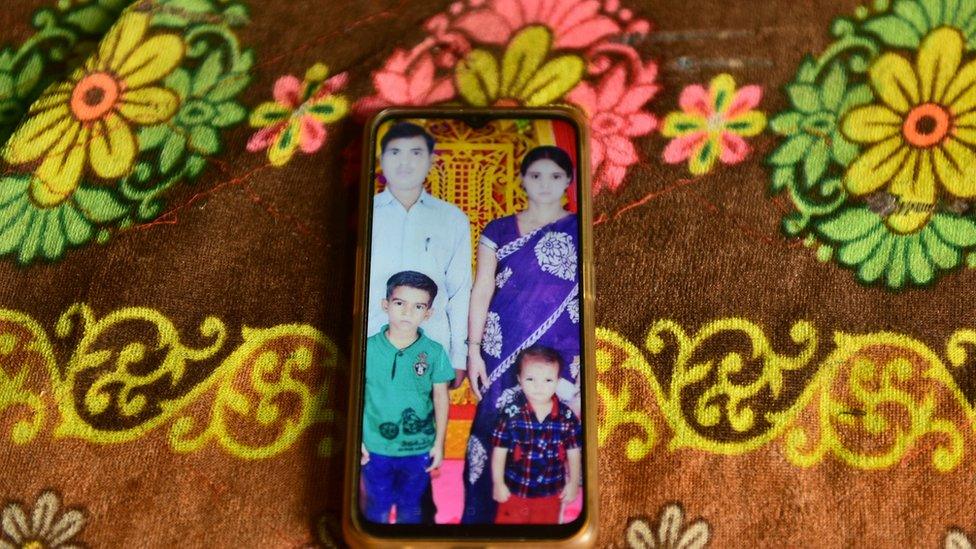

Rajan Yadav and his son, Nitin

When Rajan Yadav heard Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announce a nationwide lockdown on 24 March to halt the spread of Covid-19, little did he know that his life was about to change forever.

He was in India's financial capital, Mumbai, where thousands arrive every day from all parts of the country to realise their dreams.

His story is no different.

Rajan came to Mumbai more than a decade ago with his wife, Sanju. He worked in factories while she took care of their 11-year-old son, Nitin, and six-year-old daughter, Nandini.

They took a gamble in 2017 when they bought a tuk-tuk with a bank loan. The vehicle-for-hire brought more money for the couple and they were able to put their children in an English-medium school, which many Indian parents consider necessary for a bright future.

But just two years later, Rajan was staring at the same auto with his wife and daughter's bodies lying next to it.

Rajan drives a tuk-tuk in Mumbai city

Rajan blames the tragedy on his decision to leave the city in May. But he really didn't have much of a choice.

The family had used up most of its savings to pay rent, repay the loan and buy groceries in March and April. They were hoping that the city would reopen in May, but the lockdown was extended again.

Out of money and options, they decided to go back to their village in Jaunpur district in Uttar Pradesh state. They applied for tickets on the special trains that were being run for migrants, but had no luck for a week.

Desperate and exhausted, they decided to undertake the 1,500-km long journey in their tuk-tuk. The family of four left Mumbai on 9 May.

Three days later, just 300km (124 miles) before their destination, a truck rammed into the tuk-tuk from behind, killing Sanju and Nandini on the spot.

Rajan's wife and daughter died in the accident

Rajan's is not an isolated story - dozens of migrant workers died while trying to flee the very cities they had helped build and run during India's unprecedented and grinding lockdown.

Migrant workers had little choice after the restrictions cut off their income and ate into their savings. In the absence of transport, men, women and children were forced to begin arduous journeys back to their villages - walking, cycling or hitching rides on tuk-tuks, lorries, water tankers and even milk vans.

While doctors were fighting against Covid-19 inside hospitals, another battle for survival was being fought on the streets and highways of India.

Images of families, some with toddlers and pregnant women in tow, trying to flee cities are hard to forget.

During a reporting assignment, I met a family of five, including three children, leaving Delhi. They had a rickety bicycle for transport and the children were visibly struggling to bear the punishing May heat.

Coronavirus: Death and despair for migrants on Indian roads

Rajan's decision to leave Mumbai was also rooted in his fears that his family might go hungry. They had packed enough food when they left Mumbai. He remembers that his wife had told the children that they were taking a road trip.

He would drive from 05:00 to 11:00. He would then rest during the day, and at 18:00 the family would be back on the road until 23:00. It was a hard journey but the prospect of being in the safety of their village kept the family going.

But only Rajan and his son, Nitin, reached the village. The next few days were spent in a daze.

"I kept thinking that all this was a bad dream," he recalls, adding that his son would often jolt him back to reality.

Nitin would not stop asking for his sister and mother but Rajan had no answers. He couldn't tell his son that the life they had built for themselves in Mumbai no longer existed.

Rajan started spending his days in the fields - sometimes he would help his brothers, but he mostly sat under a tree staring at the sky.

He hardly spoke to anybody, not even to Nitin, who was being looked after by his grandparents.

"I kept questioning my decision to flee the city. Did I hurry? Did I try hard enough to make some money during the lockdown? My mind was full of questions but I had no answers," he says.

Three months passed like this and his parents began to worry about his mental health. Then an innocent question from Nitin punctured his relentless grief.

"Papa, mama wanted me to become a doctor, do you think it's still possible. Are you going to leave me in the village?" Nitin asked.

Rajan says he promised his wife he would educate Nitin

It made Rajan remember the promise he had made to Sanju that their children's education would always come first.

He suddenly realised that he hadn't been paying attention to Nitin. He started thinking about his son's future but returning to Mumbai was still not on his mind.

"It was not possible," he says.

He didn't want to return to the city without Sanju. "How could I even think about that? She was an equal partner in my success. Mumbai became my home because of her. There was no life in Mumbai without her," he says.

There were also practical issues to consider. The tuk-tuk, the family's main source of income, was badly damaged, and he didn't have enough money to get it repaired.

But he was determined to fulfil the promise he had made to Sanju. He sought help from local politicians and officials, but nobody helped.

Rajan and Nitin are now back in Mumbai

Then his parents advised him to sell Sanju's jewellery to arrange funds. But he was against the idea. The jewellery reminded him of Sanju and their happy times together.

"It was like selling the last piece of happiness I had. It felt like I was being told to sell the last piece of Sanju's memory."

But Rajan knew that Sanju would want him to do everything possible to give Nitin a good education. "That's how she was - she didn't want our children to go through the hardships we had to endure."

He finally relented and the tuk-tuk was repaired. But the money was not enough to send it to Mumbai in a truck.

The cheaper option was to drive it back but the thought of going back on the highway sent shivers down his spine. The loud noise the truck made when it rammed into the tuk-tuk was still fresh in his mind.

"It was a mental battle that I had to fight. I would sit in the tuk-tuk and pretend to drive it to get confidence."

Rajan is slowly rebuilding his life without Sanju

After struggling for weeks, he decided to leave the village in early November with Nitin.

"I avoided the stretch where the accident had happened. But I could not ignore the absence of Sanju and Nandini."

He realised during the journey that Nitin was showing maturity beyond his years. "He kept asking how I was doing and kept telling me that everything was going to be fine. Sanju was his world but now I was all he had," Rajan says.

"And I was now determined to ensure that he got everything that his mother wanted him to get."

The father and son reached Mumbai after four days. Their first task was to find a place to stay.

A friend gave them a corner in a room he was renting. Mumbai is notoriously crowded and expensive, so renting even a small room is often a challenge.

The first few days were tough. Grief had returned for Rajan as he was struggling to see a future without Sanju in Mumbai.

He eventually rented a room but it wasn't home. He started spending most of the day locked up in the room - partly out of grief but also because coronavirus was still ravaging the city and he didn't want to take a chance.

Rajan had no choice but to return to work

But the money he had saved soon started to run out, and he had to get back on the road with his tuk-tuk. That's a choice millions of daily-wage workers have to make every day in India.

It's a constant battle between hunger and the risk of infection. But the fear of hunger always wins. Staying at home is a luxury that most migrant workers cannot afford.

The first few days after he got back on the road were tough as not many people were willing to take public transport and his income was meagre.

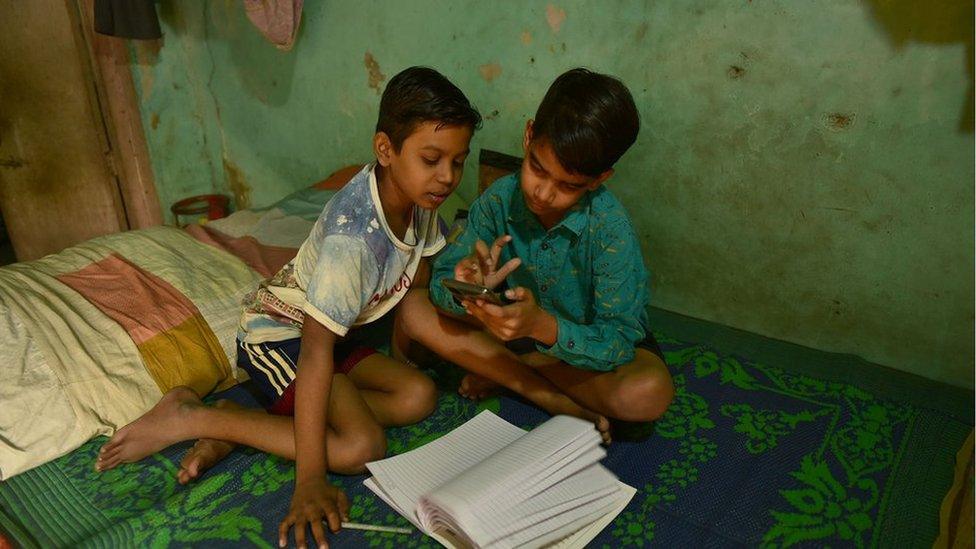

He was barely managing to pay for Nitin's online classes. It didn't help that he had to also run the house and look after Nitin. "Sanju took care for everything. I just had to ride my tuk-tuk and earn money."

But now Rajan wakes up around 6am to cook for himself and Nitin, and then he helps his son with homework before his online classes start at 9am.

He leaves the house and comes back home in the afternoon to cook lunch, and then leaves again in the evening only to return around midnight.

Rajan is hopeful about the vaccine but also anxious about whether he will get it in time

Neighbours look after Nitin when he is not around.

"I spent most of my time on the road waiting for passengers. Some days are decent but there are days when I get only two to three rides."

He desperately wants the world to become "normal again" for his business to pick up. New about the imminent arrival of a Covid-19 vaccine has given him hope, but he also has questions.

"Will poor people like me get the vaccine? I am risking my life every day. I worry what will happen to my son if I get Covid. I am not sure anybody is thinking about poor people like me. They didn't think about us before announcing the lockdown," he says.

"If they had, my Sanju and Nandini would still be alive."

Photographs by Ritesh Uttamchandani

Migrant workers paid heaviest price for Covid crisis

Related topics

- Published20 May 2020

- Published24 May 2020