Koo v Twitter: Why India's government is favouring a social media newcomer

- Published

The Koo logo is becoming an increasingly common sight on Indian phones

A little yellow chick is gaining prominence in India as a result of tensions between Twitter and the Indian government.

Koo, a new microblogging app, is being used by government departments in preference to its far larger US-based rival.

Twitter's 'double standards'

India's government had demanded that Twitter take down certain accounts it claimed were spreading fake news.

It accused Twitter of "double standards", by acting against those accused of spreading false or misleading information during the siege of the US Capitol building, but not against those acting in a similar fashion during protests at Delhi's Red Fort on 26 January.

Twitter initially complied but then reversed its decision, reinstating suspended accounts.

The lists of accounts the government wanted blocked included those of journalists, news organisations and opposition politicians.

Meanwhile, supporters of the Indian government, including ruling party politicians, have been voting with their fingers and using Koo's new platform to express their opinions. They've also shared hashtags calling for Twitter to be banned in India.

What can Koo do?

Koo's particular attraction for Indian microbloggers is that it currently operates in five national languages, as well as English, with plans to introduce 12 more.

Launched in March last year, it has received an award from the Indian government, which is trying to push for greater self-reliance.

Koo functions in a very similar way to Twitter and claims to have attracted three million downloads since its launch, a third of which it describes as active users.

Who are Koo's backers?

Earlier this month, Koo's parent company, Bombinate Technologies based in Bangalore, raised $4.1m (£3m) in funding for the project.

One of its principal backers is Mohandas Pai, well-known in India as the co-founder of the IT giant Infosys and a vocal supporter of India's BJP-led government.

With its "made in India" push, many users on Twitter had pointed out that it also had Chinese support.

But Koo chief executive Aprameya Radhakrishna says that although there had been some Chinese-based investment early on, this was no longer the case.

Parallels are being drawn to the move by Donald Trump's supporters away from Twitter towards sites such as Parler

Is Koo India's Parler?

With several ministers and BJP supporters throwing their weight behind the India-made app, many have drawn parallels to the US-based social media app, Parler.

Parler positioned itself as a "free speech" platform, and quickly became popular with supporters of former US President Donald Trump, as well as conspiracy theory groups such as QAnon, many of whom had become disillusioned with Twitter.

Twitter's loss has been Koo's gain, as several Indian ministers and government departments, as well as some celebrities, have created accounts.

Many of their supporters and followers have also followed them on to the new app.

Recently, India's electronics and information technology minister, Ravi Shankar Prasad, said he had now more than 500,000 followers on the app. His ministry's account has gained more than 160,000 over the past few days.

"We are humbled and at the same time excited by the adoption and encouragement by so many noteworthy personalities, and recently the entry of the topmost government offices of the country on to Koo," Mr Radhakrishna said in a statement.

Indian ministries are now favouring Koo as their chosen means of communication

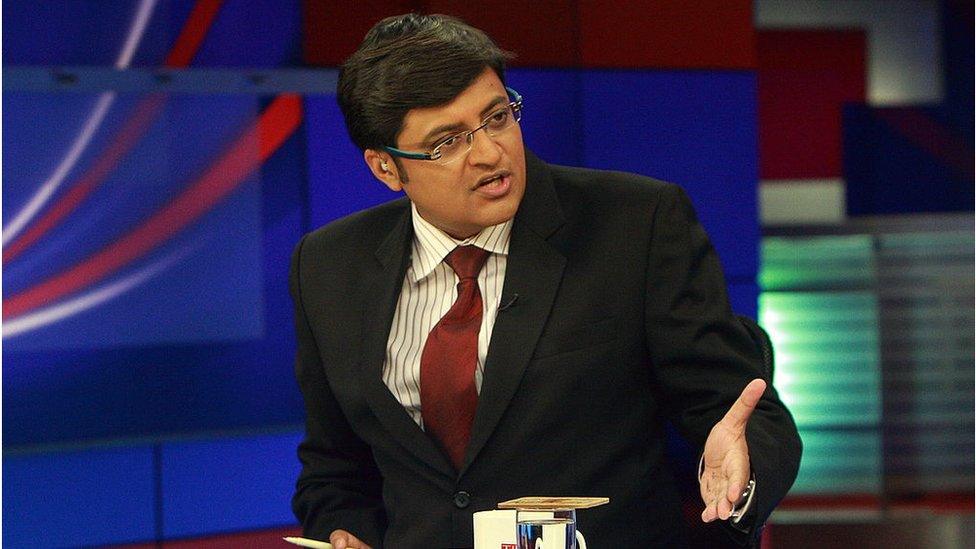

Last month a local television station, Republic TV, announced an editorial partnership with Koo.

It claims to be India's most-watched channel, but has come under scrutiny for its partisanship towards the BJP.

Many of the most popular posts on Koo get featured on the channel, and trending hashtags are promoted on TV programmes.

Weibo is a Chinese microblogging site

Some have suggested similarities with the Chinese social messaging app Weibo, because of its close association with government and its supporters.

Digital activist Nikhil Pahwa says India's self-reliance push goes against the trend towards global platforms: "I am worried that there might be a future in India where there are no global platforms operating."

Mr Pahwa is also concerned that its lack of effective content moderation opens the door for extreme views, because on any social media platform "there is a vast amount of hate speech even under real names and authenticated IDs".

Koo and Parler are not the only apps that have emerged as competitors of Twitter. Other platforms such as Mastodon and Tooter have also come up, but have failed to take off or build a loyal user base.

Mastodon gained popularity in India in 2019, when a prominent Indian lawyer's account was suspended by Twitter.

Many Indian liberals migrated to it at the time, accusing Twitter of arbitrarily blocking the account without giving an explanation.

But most of those who had left eventually returned to Twitter.

"No-one has been able to reach Twitter's scale," says Mr Pahwa, "because it gives us access to news and information from a global base of users."

Related topics

- Published12 February 2021

- Published22 November 2020