Arnab Goswami: India's most loved and loathed TV anchor

- Published

Arnab Goswami is a controversial Indian news anchor

Arnab Goswami, arguably India's most controversial TV anchor, became the story when he was arrested recently over a suicide case. He denies the charges and has been granted bail, but the case only adds to his polarising personality, reports BBC's Yogita Limaye.

"In a country where 80% of the population is Hindu, it's become a crime to be Hindu," Arnab Goswami declared on the prime time show of his Hindi language TV station Republic Bharat in April.

"I ask today that if a Muslim cleric or Catholic priest had been killed, would people be quiet?"

He was speaking about an incident where two Hindu "godmen" travelling in a car, and their driver, were lynched by a mob.

Police said the men had been mistaken for child kidnappers. The attackers and victims were all Hindu. But for nearly a week, the Republic network ran programmes claiming the victims' Hindu identity was a motive for the crime, echoing an unfounded theory floated by some members of India's governing Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP).

Mr Goswami's supporters took to the streets after his arrest

This, critics say, is the real danger of Mr Goswami's brash, cacophonic and often partisan coverage.

They believe viewers of his network are being drip-fed false information, divisive and inflammatory views, and propaganda for the Hindu nationalist BJP - its six years in power have been linked to the increased marginalisation of India's 200 million Muslims.

Mr Goswami and Republic TV didn't respond to the BBC's request for an interview, or answer questions about allegations of airing fake and inflammatory news, or partisanship towards the BJP.

A contentious style

Mr Goswami is certainly not the first to adopt this manner of coverage but he has made it louder and more aggressive than ever before. The tone is often polarising, tapping into India's religious fault lines.

In April, for instance, he falsely accused a Muslim group Tablighi Jamaat for violating lockdown orders, and called on India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi to "lock up their leadership".

In the early days of the pandemic, the group's gathering in Delhi was linked to at least a 1,000 covid cases across the country. The event's organisers insisted the congregation had been held before the government imposed a lockdown, a claim which has now been upheld by many courts in India.

But misleading broadcasts by Republic and other networks triggered Islamophobic reactions on social media.

"If there is one culprit for what we are going through as a nation in an aggravated manner, like it or not, it is the Tablighi Jamaat," Mr Goswami said in one of his many contentious segments.

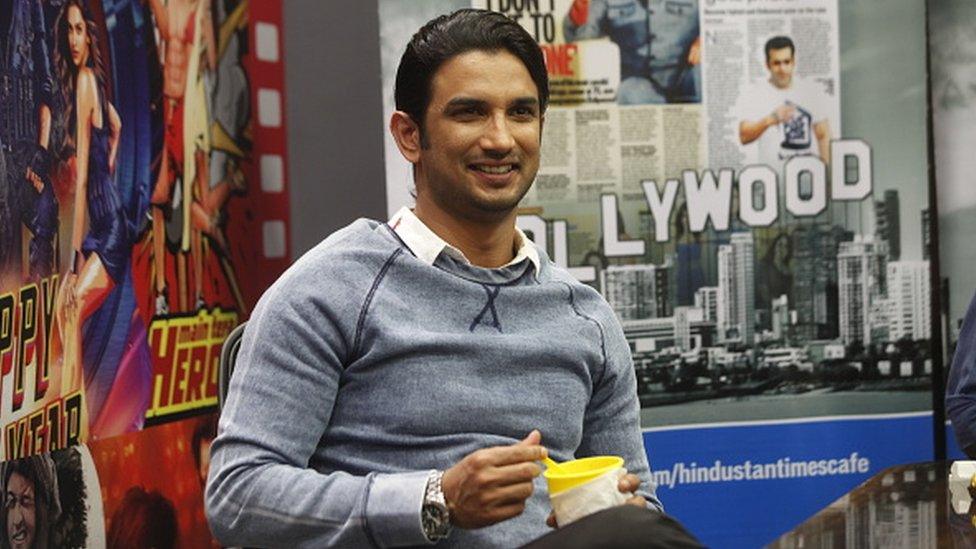

In July, the network turned its lens on the death of Bollywood actor Sushant Singh Rajput, who police said had killed himself.

But Singh's family registered a police complaint against his girlfriend, actress Rhea Chakraborty, alleging abetment to suicide.

Ms Chakraborty has denied the charges, but they have sparked a relentless wave of vitriolic and misogynistic coverage - Republic ran a campaign calling for her to be arrested on charges of abetting Singh's suicide and displayed hashtags on screen like #ArrestRheaNow.

"A comparison that people love to make in India is between Republic TV and Fox News, but I think that is a bit misplaced," says Manisha Pande, executive editor at Newslaundry, which runs a weekly critique of Indian news media. "While Fox News is seen as partisan and pro-Trump, Republic TV is outright propaganda and it often spreads misinformation in service of the current national government."

"What Republic does is it sort of demonises people, often people who don't have the power to fight back, whether it's activists, young students, members of minority communities, or protesters."

The fans and the critics

Republic claims it's India's most-watched news network, an assertion that was widely believed because of the numbers the channels racked up on television ratings platforms. But the figures are now disputed and Mr Goswami and Republic are being investigated for rigging them, an allegation they have denied.

But it's clear that Mr Goswami has a large and ardent following.

"The first channel I switch on when I get home at night is Republic. Arnab Goswami is very bold and attempts to tell the truth to the public," says Giridhar Pasupulety, a financial consultant.

When asked if he was bothered by allegations that Republic runs fake news, he said: "I don't believe that. He only tells us the truth after investigation."

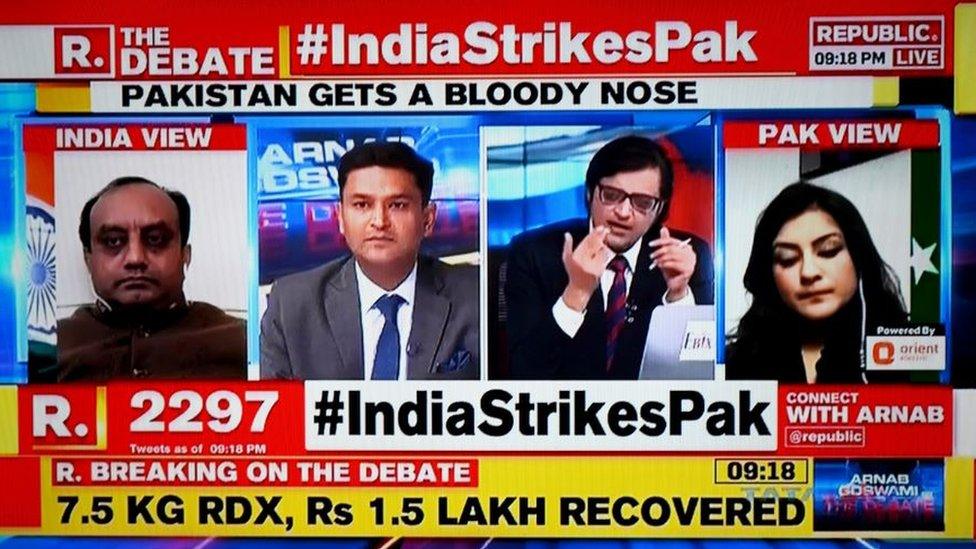

Mr Goswami's nightly broadcasts are hugely popular

"It's a kind of flashy journalism, but it's required to get the message across. It's kind of a show business as well. Ignore the flashiness and look at the information being given, which is different to what other channels are showing," says Lachman Adnani, an accountant.

Author Shobhaa De believes this kind of influence is dangerous. "We need better scrutiny, more checks and balances in place. We certainly can do without this brand of hectoring and untruth, trying to pass off as 'investigative journalism'," she says.

How it all began

Mr Goswami was born in the north-eastern state of Assam. The son of an army officer, he graduated from Delhi University and then earned a scholarship for a master's programme at Oxford University.

He started his career at The Telegraph newspaper in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), before joining NDTV, which was among the first private news channels in India. Former colleagues remember him as a balanced presenter who steered dignified debates.

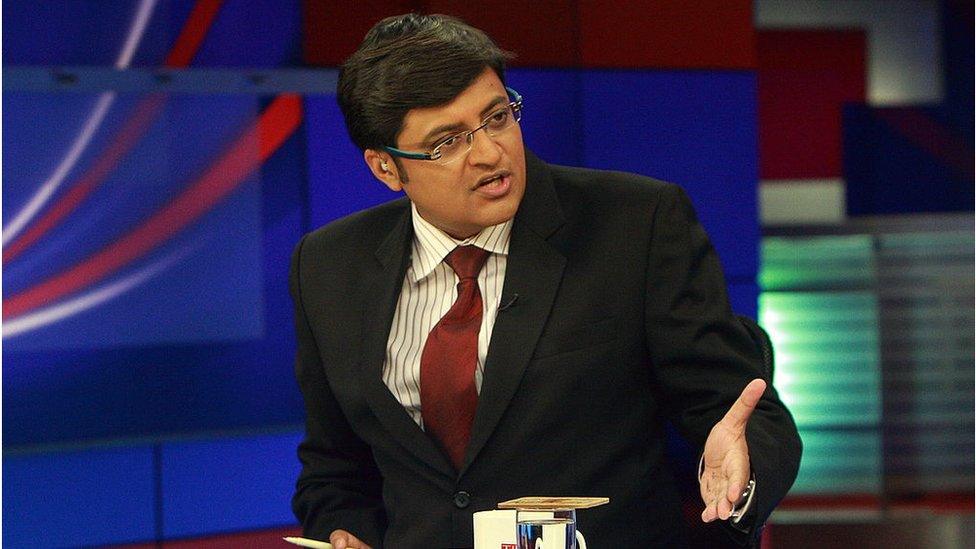

It was after he moved to the channel Times Now, which launched with him as its main face in 2006, that his on-screen persona evolved into what it is today. He tapped into the pulse of India's middle class, which was angry at the then Congress party-led government for security failures during the 2008 Mumbai attacks, and for corruption scandals. He quickly became a household name in urban India.

Mr Goswami's image transformed during his years at Times Now

At Republic, which he founded in 2017, Mr Goswami became even more strident and partisan. In 2019, he also launched a channel in the Hindi language, extending his popularity beyond cities.

Ms De used to participate in Mr Goswami's programmes. "I appeared frequently on his shows as a panellist at a time when he had credibility as a journalist," she says. "I stopped when I lost respect for him as an unbiased professional doing his job. He has been out of line on several fronts, and there are serious questions about his integrity these days."

Mr Goswami was recently arrested over the death of an architect who designed his studio. He and Republic TV network deny allegations that they owed money to the architect.

Many believe he was targeted because of his strident criticism of the Maharashtra government, led by the Shiv Sena, an estranged former ally of BJP.

Mr Goswami's political clout became evident when several BJP ministers came out in his support, calling his arrest an attack on press freedom in India.

It was a striking claim because dozens of journalists over the past few years have been arrested or detained in states governed by the BJP. Many have been slapped with charges such as terrorism and sedition. But party leaders and ministers have not spoken up on their behalf.

India now ranks 142 out of 180 countries on the press freedom index released by Reporters Without Borders - it dropped six places over the past five years.

Mr Goswami cheers after being released from jail on bail

In an interview to Gulf News in 2018, Mr Goswami was asked about bias towards the BJP. "This is an unverified complaint. In fact, we are the most robust in our criticism of the BJP on issues when it needs to be criticised," he said.

Last week, Mr Goswami was released after seven days in custody. His return to his newsroom was broadcast live on his network with the hashtag #Arnabisback prominently displayed.

His team greeted him with applause and cheering. "They are going after us for our journalism," Mr Goswami proclaimed in a dramatic speech. "I will decide the boundaries of our journalism."

"What Republic does cannot be called journalism," says Ms Pande. "It's just good reality TV. But he's successfully able to colour people's opinions. And that's troubling in a democracy."

Additional reporting by Aakriti Thapar

Read more stories by Yogita Limaye

- Published11 September 2020