Sidhique Kappan: Jailed and 'tortured' for trying to report a rape

- Published

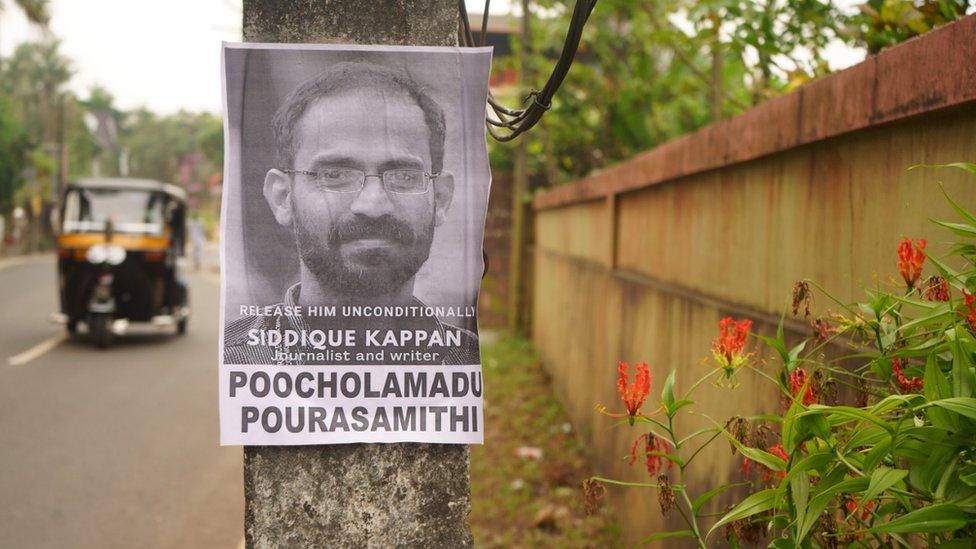

Posters have come up in Kerala calling for journalist Sidhique Kappan's release

On the morning of 5 October last year, I headed to a village in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh to cover what had come to be known as "the Hathras case".

A few days earlier, a 19-year-old Dalit woman had died after she was allegedly gang-raped by four of her upper-caste neighbours in the village of Bhulgarhi in Hathras.

The story of the brutal assault, the woman's death and a forced cremation in the middle of the night by the police without her family's consent had made headlines around the world.

At around 10 in the morning, I reached the young woman's home and met her grieving family - relatives and neighbours who told me about a pretty teenager with a shy smile and long dark hair.

They told me about the wounds inflicted on her body and the callous manner in which the police and the government had treated her in life and death.

On the same morning, Sidhique Kappan, a 41-year-old journalist for the Malayalam-language news portal Azhimukham, also set out for Bhulgarhi, travelling from Delhi where he had been based for nine years.

But his journey turned out to be very different to mine.

Mr Kappan was arrested with three other men in a car about 42km (26 miles) short of Hathras. Last week, he completed his 150th day in jail.

In October, I met the family of the 19-year-old woman who had died after alleging gangrape

In the police lockup that night - according to an account he gave his family and lawyer - Mr Kappan was "dragged and beaten with sticks on thighs, slapped on face, forced to stay awake from 6pm to 6am on the pretext of questioning and subjected to serious mental torture".

A diabetic, he was also denied his medication, he said.

The police have denied his allegations. They say they arrested Mr Kappan because he was going to Hathras as part of a conspiracy to create law and order trouble and foment caste riots. The other three men in the car have been accused of similar offences.

Police said Mr Kappan's fellow passengers were from the Popular Front of India (PFI) - a Kerala-based hardline Muslim organisation that authorities often accuse of having links with extremist groups and the Uttar Pradesh government wants it outlawed.

They said that Mr Kappan was pretending to be a journalist from a defunct newspaper while in reality he too was a member of the PFI - a claim denied by the Kerala Union of Working Journalists, Mr Kappan's lawyer, and the PFI.

The journalists' union, of which Mr Kappan is an office bearer, has accused the Uttar Pradesh police of making an "absolutely false and incorrect statement" and called his detention "illegal".

The union insists that Mr Kappan is "only a journalist" and "attempted to visit Hathras in discharge of his journalistic duty". The union has filed a petition in the Supreme Court seeking his release. His employer, Azhimukham, also issued a statement saying he was on their payroll and was going to Hathras on assignment.

Raihanath Sidhiqui says her husband is innocent

Lawyer Wills Mathews, who is representing both Mr Kappan and the journalists' union, told the BBC that initially his client was charged with minor bailable offences. But two days later, police accused Mr Kappan of sedition and invoked the dreaded Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) - an anti-terrorism law that makes bail almost impossible.

Mr Mathews said his client was a "100% neutral, independent journalist".

"Sharing a taxi with some people doesn't make him guilty," he said.

"A journalist has to meet people from different walks of life, including those accused of crimes, and just being in the company of other accused can't be a reason for arrest," Mr Matthews added.

For weeks after his arrest, according to court documents, Mr Kappan was allowed no contact with the outside world.

He was allowed to make the first phone call to his family on 2 November - 29 days after his arrest - and spoke to his wife eight days after that. Mr Mathews was allowed to meet him only after 47 days, after he had petitioned the Supreme Court.

Raihanath, Mr Kappan's wife, told me on the phone from her home in her village in Kerala's Malappuram district that until his phone call on 2 November, she was "not even sure that he was alive".

Then last month, the Supreme Court granted him a five-day interim bail to visit his 90-year-old mother, who was bedridden and ailing. For the four days he was there, six policemen from Uttar Pradesh and two dozen from the state stood guard outside.

In February, Sidhique Kappan was granted bail for five-days to visit his ailing mother

It was a fraught visit, Raihanath said. "He was tense about his mother's poor health, he was worried about our finances and the future of our three children," she said. She insists her husband has done nothing wrong and says he has been targeted because he is a Muslim.

According to Raihanath, the police repeatedly asked her husband if he ate beef (many Hindus revere cows, and in recent years Muslims have been targeted for eating beef or transporting cattle). She said they questioned him about how many times he had met Dr Zakir Naik, a controversial Islamic preacher charged with hate speech and money laundering and living in exile in Malaysia (Mr Naik denies the allegations) and asked him why Muslims have an affinity to Dalits - formerly known as "untouchables".

Abhilash MR, a Senior Supreme Court lawyer, told me: "If someone were to say Sidhique Kappan's arrest is Islamophobic, I would endorse that opinion".

Mr Abhilash, who said he had been following the case closely, called it a "political witch-hunt" and a "case of political persecution". Mr Kappan's "fundamental rights are being trampled upon", he said.

Critics have accused the present government in Uttar Pradesh, led by the controversial saffron-robed Hindu monk Yogi Adityanath, of unfairly targeting Muslims. Yogi Adityanath has been described as India's most divisive and abusive politician and accused of using his election rallies to whip up anti-Muslim hysteria.

His government and the police force attracted global condemnation for the way it responded to the young woman's gang-rape and death in Hathras, especially after the authorities cremated her body in the middle of the night - keeping her family and media away from her funeral pyre.

Police in Uttar Pradesh were criticised for attacking opposition activists protesting against the Hathras rape case

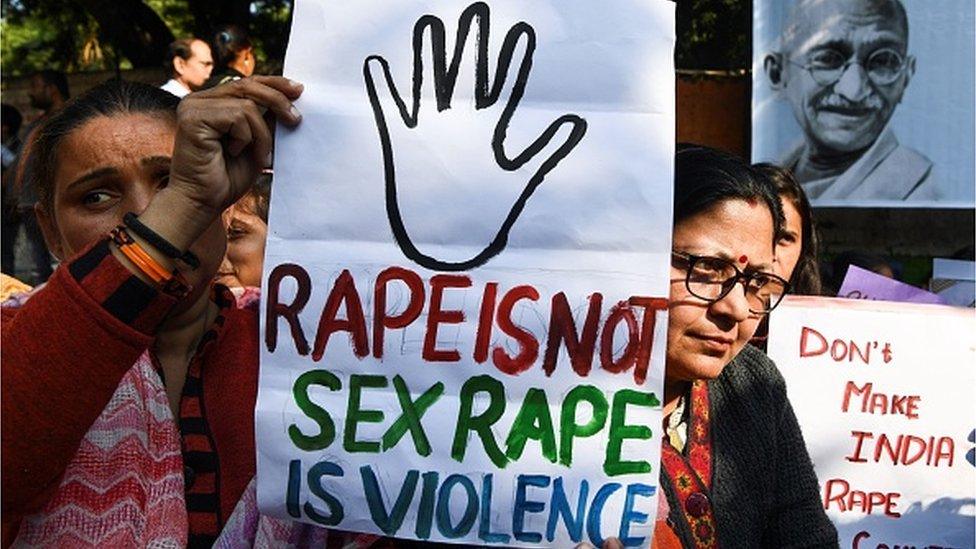

In the days after the death of the young Dalit woman, protests were held across India. In Uttar Pradesh, officers were heavily criticised for beating protesters with sticks in an attempt to stop them from visiting the victim's family. Opposition leaders who had joined the protest were shoved around.

On 4 October, a day before Mr Kappan and I had headed separately for Hathras, Mr Adityanath claimed, external that there was "an international conspiracy" to tarnish the image of the state and that "the incident was being exploited by those who were upset at his government's progress".

The incident has worried press freedom activists, who say they fear India is becoming increasingly unsafe for journalists. Last year, the country was ranked 142 on the 180-country World Press Freedom Index, compiled annually by Reporters Without Borders - a fall of two places from the previous year.

In February, police filed criminal charges against eight journalists who covered the farmers' protests in Delhi. Female journalists and those from the Muslim community are especially picked on for trolling on social media.

The police had not been able to produce a single piece of incriminating evidence against Mr Kappan, said Mr Abhilash, the Supreme Court lawyer. They had succeeded in one thing however, he said: sending a warning to reporters not to head for Hathras.

Mr Kappan's arrest was "different from arresting a regular person", said his lawyer Mr Matthews. "Silencing media is the end of democracy," he said.

Read more on our coverage of the Hathras rape case:

Delhi Nirbhaya rape death penalty: How the case galvanised India

Related topics

- Published10 October 2020

- Published8 October 2020

- Published4 March 2021