Amitabh Bachchan and India's battle to preserve its film heritage

- Published

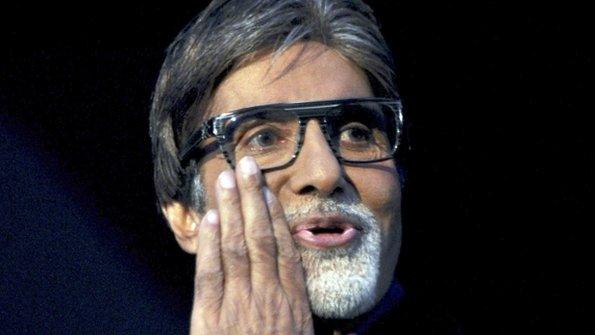

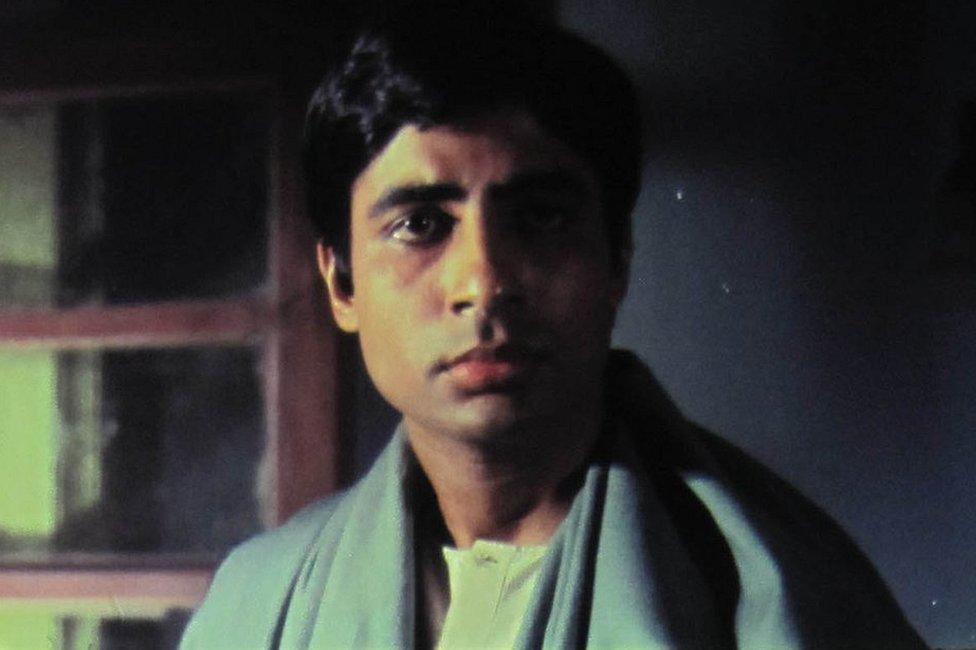

A release print of the 1971 Bollywood hit Anand, starring Amitabh Bachchan, has been preserved

For decades, Amitabh Bachchan preserved some 60 of his films in an air-conditioned room in his bungalow in the western city of Mumbai.

Five years ago, the Bollywood superstar handed over the prints to a temperature-controlled film archive run by a city-based non-profit, which had begun restoring and preserving Indian films. Led by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, an award-winning filmmaker, archivist and restorer, the Film Heritage Foundation, external has been at the forefront of these efforts. It has "built an international reputation for excellence", according to director Christopher Nolan, and Bachchan is its brand ambassador.

For years he has been tirelessly advocating and actively helping in trying to preserve India's fast-decaying film heritage.

And on Friday, Bachchan was feted, external for this little-known facet of his work. The 78-year-old actor was conferred this year's International Federation of Film Archives award, external. Nolan and fellow filmmaker Martin Scorsese gave away the award, whose stellar past recipients include the two acclaimed directors themselves and such auteurs as Ingmar Bergman, Agnes Varda and Jean-Luc-Godard.

Bachchan, Dungarpur says, has "always been deeply invested" in the idea of preserving and archiving cinema. During a conversation, the star once agonised over the fact that he couldn't watch some of the earlier films of the thespian Dilip Kumar because "they were simply lost".

Dungarpur found 200 films dumped in a warehouse in Mumbai

India has 10 major film industries - including Bollywood, the world's largest - and produces close to 2,000 films a year in some 36 languages.

But it has only two film archives - a state-run one in the western city of Pune and the non-profit, run by Dungarpur. "This is woefully inadequate given our rich and prolific film history," Dungarpur says.

Not surprisingly, much of India's storied film heritage has been lost and damaged because of spotty conservation and preservation of film.

India's first talkie Alam Ara, external (1931) and its first locally-made colour film Kisan Kanya, external (1937) are untraceable. Newer films have fared no better. Original footage of a documentary on freedom heroine Lakhshmi Sahgal made by Sai Paranjpye (1977) and Shyam Benegal's Bharat Ek Khoj (1988) no longer exists. The negative of a 2009 film called Magadheera, external made by SS Rajamouli "disappeared in just six years", according to the director.

As Dungarpur tells the grim story, only 29 of 1,138 silent films made in India survive. Some 80% of the more than 2,000 films made in Mumbai - then Bombay - between 1931 and 1950 are unavailable for viewing.

Last year, Dungarpur and his team found 200 films languishing in sacks in a warehouse in Mumbai. "They were prints and negatives, and someone had just dumped them," he says.

A still from the 1958 Bollywood drama Night Club, now preserved in the archive

That's not all. According to government auditors 31,000 reels of film held by the state-run film archives have been lost, external or destroyed.

In 2003, more than 600 films were reportedly damaged in a fire, external in the state-run archive - among them were original prints of the last few existing reels of the 1913 classic Raja Harishchandra, India's first silent film. "You have to respect your past. To respect your past you need to preserve and restore your films," says director Gautam Ghosh.

Before digital arrived, films were usually preserved as original negatives, duplicates of those negatives and prints that were released for viewing. After most Indian filmmakers stopped shooting on film in 2014, Dungarpur says, many film labs digitised their stock, and threw away the negatives, thinking that they had no use for them. "The original camera negative has a much higher resolution than digital today. That's what they didn't know."

Now, preservationists in India mainly work on prints.

"It's a complete disaster. We had to try create a completely new awareness about celluloid film and its history".

A preserved still of the 1954 film, Sher Dil

Over the last six years, Dungarpur and a faculty comprising of experts from leading film archives and museums around the world have held workshops all over India and trained over 300 people in restoration and preservation of film.

The foundation has collected and preserved more than 500 films of top Indian filmmakers, footage of the independence movement and Indian home movies in its facility in Mumbai. Its collection includes such rarities as two 16mm reels of Oscar-winning director Satyajit Ray in conversation with legendary Italian-American director Frank Capra. Dungarpur also has an impressive collection of Indian film memorabilia: tens of thousands of old photographs, photo negatives and film posters.

Bachchan has always been outspoken about the need to take charge of India's crumbling film heritage. Two years ago, at an international film festival in Kolkta, he said: "Our generation recognises the immense contribution of the legends of Indian cinema, but sadly most of their films have gone up in flames or have been discarded on the scrap heap".

"Very little of our film heritage survives and if we do not take urgent steps to save what remains, in another 100 years there will be no memory of all those who came before us and captured our lives through the moving image."

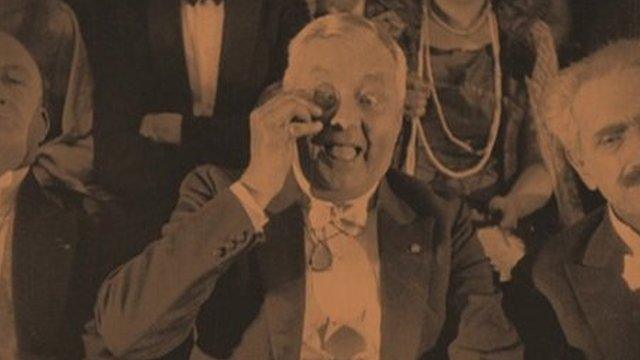

Raja Harishchandra, India's first silent film, was released on 3 May 1913

- Published2 May 2013

- Published24 May 2012

- Published11 October 2012