The 'daughter of Bengal' taking on India's PM

- Published

Mamata Banerjee is the leader of the regional Trinamool Congress party

The most high-profile contest in India's ongoing state elections is under way in West Bengal. Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee of the regional Trinamool Congress party is taking on a former aide, Suvendu Adhikari, in the Nandigram constituency. Mr Adhikari, a powerful local leader, switched allegiance and defected to the BJP before the polls. Will he be able to take on the redoubtable Ms Banerjee in his own fief? Last week, I had travelled to West Bengal to find how Ms Banerjee, seeking a third consecutive term in power, is fighting the battle of her life against a resurgent BJP.

On a sweltering afternoon, India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi is working the crowd at a campaign meeting, some 160km (99 miles) south of the eastern city of Kolkata in West Bengal state.

"You gave her an opportunity to work for 10 years. Now give us a chance," Mr Modi says. The woman in question is Mamata Banerjee, the firebrand leader of Trinamool Congress (TMC), a regional party that has been ruling the state for a decade.

Now Mr Modi, a folksy orator, slips into thickly accented Bengali, much of the amusement of many in the crowd. He launches into a broadside against Ms Banerjee, who is better known in Bengal as "didi" or elder sister, a moniker invented by her supporters.

"Didi, o Mamata didi. You say we are outsiders. But the land of Bengal doesn't regard anyone as an outsider," says Mr Modi. "Nobody is an outsider here."

Ms Banerjee has framed the challenge from Mr Modi's Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as one between the insiders (Bengalis) and the outsiders (the largely Hindi-speaking BJP, which runs the federal government).

Mr Modi is the face of BJP's campaign in Bengal

The 66-year-old leader is tapping into, at once, nativist and federalist sentiments. The "othering" of a powerful federal party is grounded in India's contested politics of federalism, says Dwaipayan Bhattacharya, a professor of political science at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Ms Banerjee has also accused the Hindu nationalist party of trying to bring "narrow, discriminatory and divisive politics in Bengal".

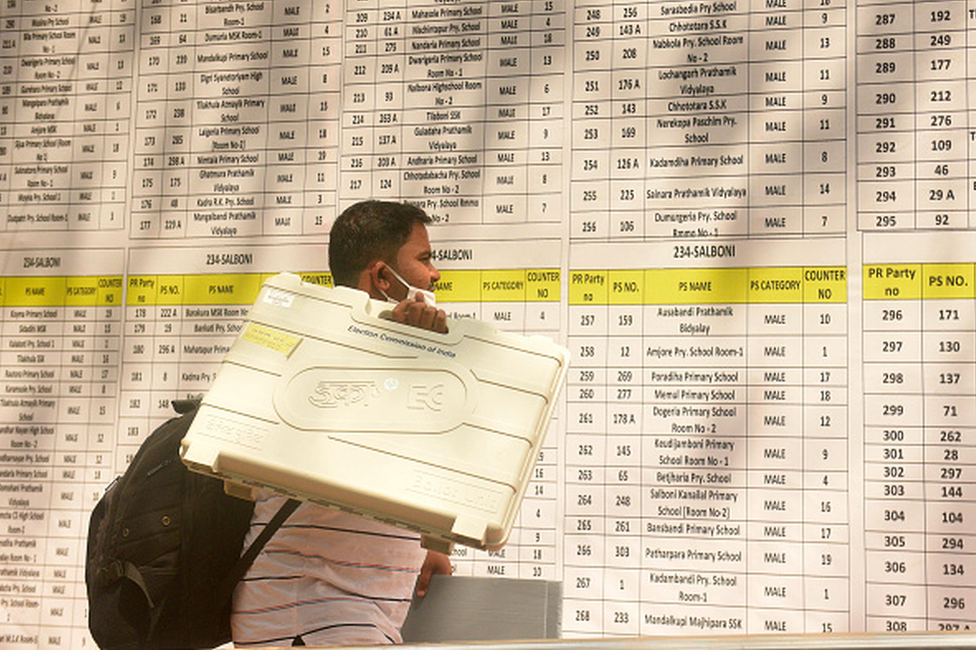

Rhetoric aside, the battle for West Bengal - where voting is staggered over eight phases and four weeks - promises to be intense. (The results of voting will not be announced until 2 May, along with four other states, including neighbouring Assam.) It is also the most significant state election in India in recent years.

West Bengal, a state of 92 million people, has never been ruled by Mr Modi's party.

The feisty Ms Banerjee stormed to power in 2011 after dislodging a Communist-led government that ruled the state for 34 years. Since then she has ruled without a break, and her party currently holds 211 of 295 seats in the outgoing state assembly. The TMC is a loosely structured, and not a particularly disciplined party. It has no ideological underpinnings. Like most of India's regional parties, it relies on the cult of personality of a charismatic leader, whose supporters also call her the "fire goddess".

Ms Banerjee is described as a 'daughter of Bengal' in the campaign

During the last assembly election in 2016, the BJP won a paltry three seats. In the parliamentary poll in 2019, it threw down the gauntlet, picking up 18 of the state's 42 parliamentary seats and 40% of the popular vote. Ms Banerjee's party won 22 seats, down a dozen seats from the 2014 ballot, and was badly bruised.

"It was a wake up call for Ms Banerjee," says Rajat Ray, a political commentator. "2021 is her existential battle".

A win for the BJP in West Bengal will be a major boost to the party. Although Mr Modi continues to be India's most popular leader, his party has been struggling to win state elections. Also, a win for a Hindu nationalist party in a state where a third of the voters are Muslims will be hugely symbolic. It will almost also extinguish any hope that India's largely rag-tag opposition harbours to take on Mr Modi's well-oiled and richly funded party in 2024 general elections.

"This election is a war for Indian democracy. If the BJP wins, Hindu majoritarian politics will have finally arrived in Bengal, a veritable last bastion," says Prashant Kishore, a political strategist, who is helping Ms Banerjee's campaign.

If Ms Banerjee wins, she is likely to emerge as a national leader because she would have defeated a powerful incumbent national party. She is also likely to emerge as a consensus opposition leader in their fight against the BJP. No other opposition leader has been able to mount a successful narrative against Mr Modi, and if she wins, Ms Banerjee could be the answer, according to Neelanjan Sircar, a senior visiting fellow at the Centre for Policy Research in Delhi.

The Communists are struggling to regain political relevance in Bengal

It may not be easy. Everywhere you travel in West Bengal, people complain that they have to pay bribes to local TMC leaders and workers to access welfare schemes - one person said party workers even wait outside banks to demand a bribe from people withdrawing welfare money transfers. The problem in West Bengal, one commentator told me, was the "politicisation of the government".

People also talk about violence against political rivals - and the arrogance of TMC workers. Dhanpat Ram Agarwal, who heads the BJP's economic cell in the state, said the more crippling malaise was the "criminalisation of politics", where opponents are "attacked and persecuted".

Yet most people don't appear to hold grudges against Ms Banerjee, who is perceived to be a personally clean and empathetic leader. Ten years of rule may have ended the euphoria around her, but her larger-than-life image remains intact, and public anger against her is muted. One commentator calls it the "paradox of anti-incumbency", external.

Mr Kishore admits that "there is anger against the local leadership, and the party". But, he says, Ms Banerjee is "holding on to her image as the girl next door, the didi".

"Her image will help mitigate the anti-incumbency. She is not hated. And her party has not imploded despite the BJP's attempts."

Also in the past 18 months, Ms Banerjee has tried to reclaim some lost ground.

Ms Banerjee has a larger than life image in Bengal

More than seven million people have reportedly called a helpline she set up to record people's complaints. Nearly 30 million people have availed of an initiative called "government at the doorstep" since December to ease delivery of a dozen welfare schemes. Public grievances over 10,000 community related schemes were sorted out through a neighbourhood' programme, the government claims.. Rural roads are being repaired on a war footing.

A slew of welfare schemes - bicycles and scholarships for students, cash transfers for girl students to continue education and health insurance - has ensured that Ms Banerjee's populist appeal is unblemished. She remains popular with women voters: some 17% of her candidates in this election are women.

In its bid to grow exponentially and take on Ms Banerjee, the BJP has poached freely from its rivals in West Bengal. More than 45 of the 282 candidates it has put up in the polls are defectors. Thirty four of them are from Ms Banerjee's party alone, mostly disgruntled local leaders who have been refused tickets. The BJP's organisation remains creaky, and it lacks a compelling local leader to take on Ms Banerjee. Many say the party doesn't have a cohesive narrative, beyond the criticism of the TMC, and promises of a "golden Bengal". It is, they reckon, mostly drawing on support from voters angry with the TMC, including those belonging to a clutch of lower castes.

Bengal is India's most significant state election in recent years

Despite the ailing Communists stitching up an alliance with a Muslim cleric and the enfeebled Congress to swing votes away from the main contestants, the battle for West Bengal is singularly bipolar. To win the state, a party has to pick up 45% of the popular votes in such a contest.

Most believe it will be a closely fought election. Even "didi", the protective elder sister, has been forced into a change of image. Kolkata's skyline is emblazoned with billboards of Ms Banerjee's smiling face, describing her as "Banglar meye" or daughter of Bengal. It's an appeal from a woman who says she is under siege from outsiders.

"It is about telling the voters that she needs your support in this crucial battle," says Mr Kishore.

This piece was originally published on 27th March and has been updated to reflect the latest news developments

Related topics

- Published15 April 2011

- Published13 May 2011

- Published19 April 2012