India coronavirus: A tribal area had oxygen while cities gasped

- Published

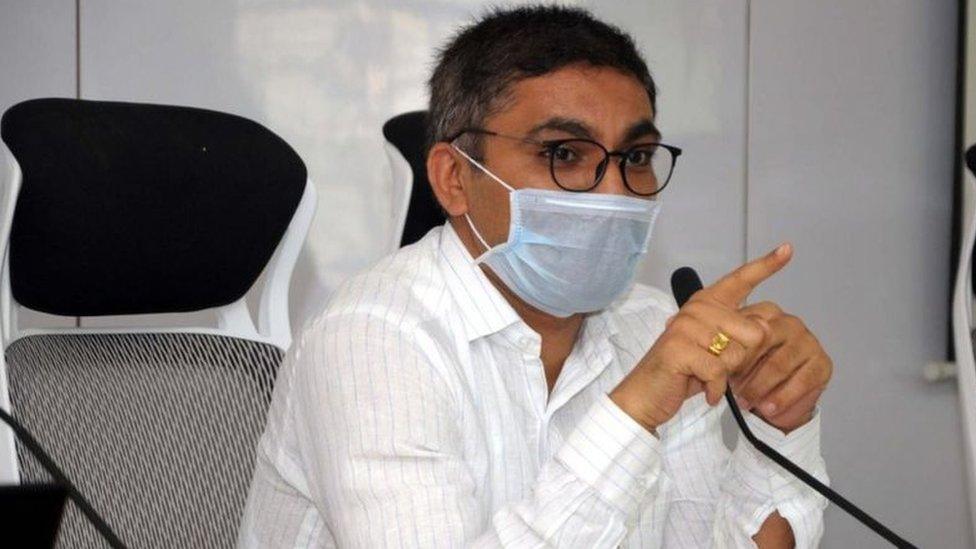

Dr Rajendra Bharud, district collector for Nandurbar, has been praised for his efforts in tacking the second wave

As India's cities and towns struggled to keep Covid patients breathing amid a severe oxygen shortage, one rural district managed to avoid the crisis, BBC Marathi's Mayank Bhagwat and Janhavee Moole report.

"There's a pattern in the pandemic and it's important to understand it," says Rajendra Bharud, the collector, or senior administrator, in Nandurbar district in India's western state of Maharashtra.

He says he realised early on that he needed to plan and prepare. And that decision certainly paid off: he has been making headlines in India for what is being called the "Nandurbar model". The remote, tribal district is being praised for ramping up resources and managing its caseload in a devastating second wave that has left even Mumbai, Maharashtra's capital and India's richest city, reeling.

How did that happen?

Anticipating a crisis

"We saw cases peaking in India after they peaked in Western countries. We had seen these countries being hit by a second wave and a third wave. So we realised it could happen here as well," Dr Bharud explains.

Maharashtra, one of India's largest states, had long been a Covid hotspot - it still accounts for about a fifth of India's Covid caseload overall, although official figures show its share of active cases dropping in recent weeks.

But in April, as the caseload mounted rapidly, Maharashtra presented an alarming scenario. It was adding more cases daily than any other state, partly given the size of its population. But it was also seeing a shortage of critical care beds and oxygen, and families found themselves travelling across districts in search of beds so they could save a loved one.

Dr Bharud, who studied to be a doctor, says his background in medicine came in handy, and he was able to see the writing on the wall.

At the height of the first wave in September last year, Nandurbar had around 1,000 active cases. But like everywhere in India, numbers dropped sharply in the following months - they fell below under 400 by the end of December.

But Dr Bharud says his administration did not let its guard down.

India's colonial-era epidemic diseases law gives district collectors a lot of powers to contain the spread of the virus - so he began preparing in September itself.

An acute oxygen shortage has gripped India in the second Covid wave

And even as cases dipped, his administration continued expanding or building infrastructure - from quarantine centres to oxygen plants - that would help fight the virus.

And they were ready when cases began to climb by the end of March - by 30 April, Nandurbar had some 7,000 active cases.

But they were not falling short of beds or running out of oxygen - a familiar sight across India's biggest cities.

Preparing for the shortage

Dr Bharud says the fact that Nandurbar was his home district helped. He personally knew the challenges that lay ahead.

One of the remotest districts in western India, Nandurbar is located amid hilly forests, bordering the states of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat. It's about 440km (270 miles) from Mumbai.

It's a relatively poor district largely populated by tribespeople with few healthcare facilities. Before the pandemic, it had just nine critical care beds and 80 oxygen beds for a population of nearly two million, says Dr Rajesh Valvi at the Nandurbar Civil Hospital.

Early in the second wave, some patients in border villages crossed into Gujarat when they found it difficult to find a hospital bed. But district officials soon converted schools and hostels into quarantine centres. And they were monitored by local primary healthcare centres - each village has one.

So patients with mild symptoms were treated quickly and only those with a serious infection went to hospital. This ensured that patients' condition did not deteriorate due to delayed care and it significantly reduced the burden on major hospitals.

They also added both critical care beds oxygen beds - now they have 148 of the former and 556 of the latter across the district. And with cases falling, some 200 beds are vacant.

The other thing the district did was increase its oxygen supply. It did not have a liquid oxygen plant because it was not an industrial district - unlike some others that were able to tap into nearby industrial resources to ramp up supply.

It also had no oxygen refill plant, which supplies the vital gas to portable cylinders. And none of the hospitals had a plant that could convert oxygen from air and directly supply it to beds via a pipeline.

"We realised we would not get enough oxygen if there is a second wave," Dr Bharud says.

So the district installed three such plants in September, February and March in two major government hospitals. And then two private hospitals in Nandurbar city followed suit.

One plant can also fill up to 125 jumbo-sized cylinders to supply air to patients in other hospitals. These plants are now producing 4.8 million litres of oxygen per day - and Nandurbar has surplus oxygen that it sends to other districts.

The district installed oxygen plants in three hospitals

They bought 30 oxygen concentrators, too, which help the breathless patients breathe more easily, for primary healthcare centres in remote villages to reduce the burden on hospitals.

They have also trained healthcare workers - including specialised "oxygen nurses" - and set up a centralised control room to monitor the situation.

Neelima Walvi, an "oxygen nurse" in Nandurbar's biggest public hospital says her sole task is to monitor the oxygen given to Covid patients to cut waste or leakage.

"If their oxygen level is over 95, I reduce the amount of oxygen given to them, say from five litres to one or two litres, depending on their condition," she says.

Every Covid hospital or centre was told to appoint such a nurse for every 50 beds. The model proved so successful that the state government has ordered other districts to do the same.

What comes next?

Since the start of the pandemic, the district has recorded 38,000 Covid cases and about 700 deaths. In the second wave, it reported its highest number of daily deaths on 4 May - 18.

Nandurbar is of course not an urban or densely populated district such as Mumbai, where the challenges are often greater. But its success, experts say, has show the value of India's vast decentralised bureaucracy that has not been harnessed enough to battle Covid.

But challenges do remain, officials and doctors say.

Inside India's rundown rural hospitals unable to cope with the Covid crisis

Dr Abhishek Payal, who has been treating Covid patients at a private hospital, says some of the shortages they faced in March and April have lessened as cases numbers appear to fall.

But, he adds, following up on patients, is an issue in such a remote district.

"A lot of the people we treat come from very far away. Once they are discharged, they cannot always return for a check-up for weeks or even months. So treating those facing long Covid is a big challenge."

He is also worried that the infection is now spreading in rural areas, where vaccine hesitancy is higher, especially among the tribal communities.

"It's not one man's job to fight Covid," Dr Bharud says. "We are focusing on how people can get treatment and vaccines in their villages so they don't have to travel far.

"We need to improve facilities further to ensure that we are ready to face the third wave."

Additional reporting by Nilesh Patil

Read more of our Covid coverage: