AI shows Bollywood obsession with fair skin and sons

- Published

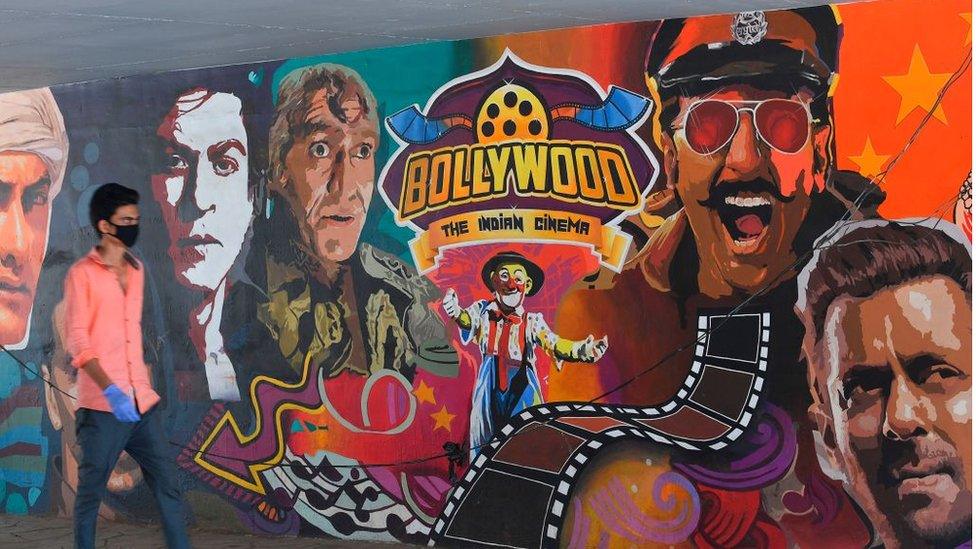

The effects of the pandemic could have a profound effect on Bollywood films

Has Bollywood - India's hugely popular Hindi film industry - become more progressive over the years?

Yes - and no - says an artificial intelligence (AI) driven study of dialogues from hundreds of films over the past 70 years.

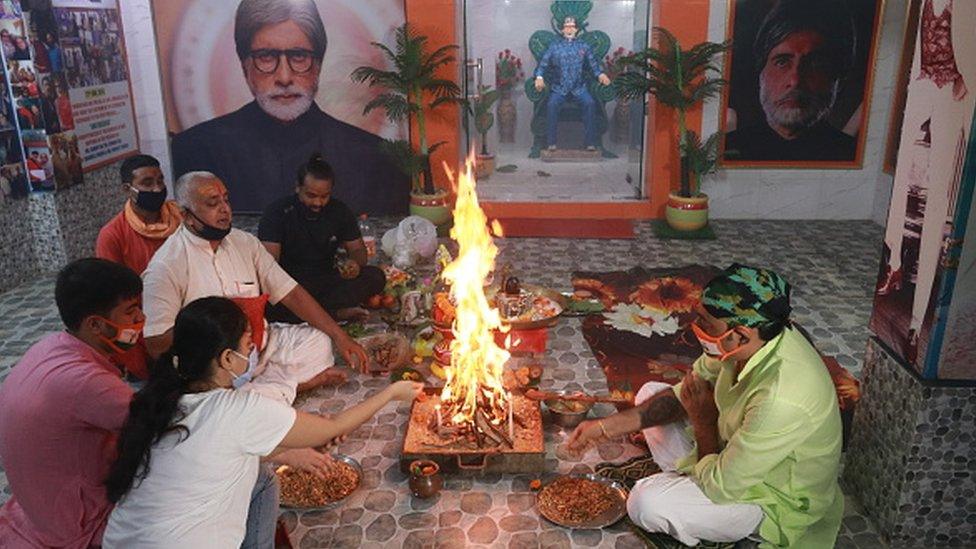

The $2.1bn (£1.5bn) industry churns out hundreds of films every year and has a massive following among Indians globally. Fans revere stars, pray for their wellbeing, even build temples to them and donate blood in their name.

Over the years, Bollywood films have also been criticised for being regressive, promoting misogyny, colourism and gender biases, but there has been no broad study into its social biases.

With the aim to fill that gap, researchers, led by Kunal Khadilkar and Ashiqur KhudaBukhsh of Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) in the US, picked 100 of the biggest commercial hits from each of the seven decades from 1950 to 2020.

The co-authors - self-confessed "huge Bollywood fans" - then fed the subtitles into automated language-processing tools to find out if - and how - Bollywood's biases have evolved over the years.

"Films act as a mirror of social biases and also have a huge impact on people's lives. Our study allowed us to see through the lens of entertainment how India has evolved in the past seven decades," Mr KhudaBukhsh told the BBC from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

To see how Bollywood compared with other major film industries in the world, the researchers also chose 700 films from Hollywood and 200 critically acclaimed films nominated in the foreign film category at the Oscars.

The study threw up some interesting results, external - Bollywood is biased, but so is Hollywood, although on most counts, a little less. And that in both the industries, social biases have reduced steadily over the past seven decades.

"We have come a long way in 70 years, but we still have a long way to go," Mr Khadilkar told the BBC.

Actress Vidya Balan has often spoken out about sexism in Bollywood

Among the questions the researchers asked were whether Bollywood reflected India's well-documented preference for sons and if the sentiment around a social evil like dowry had changed. The results showed a huge decline.

"In the 1950s and 60s, 74% of babies born in films were boys - in the 2000s, that number had come down to 54%. It was a huge jump, but the gender ratio was still skewed," Mr KhudaBukhsh said.

He blamed "India's son preference" on dowry - a practice that was outlawed in 1961. But in most arranged marriages - and nine out of 10 are still arranged - families of brides are expected to pay cash, jewellery and gifts, and thousands of brides are killed annually for bringing insufficient dowries.

"When we searched the database, we found that in older films, words such as money, debt, jewellery, fees, and loan were used alongside dowry, indicating compliance to the practice. But modern films exhibited non-compliance through words like guts and refused and indicated some of the consequences of such non-compliance with words like divorce and trouble," Mr KhudaBuksh said.

The study found that some of the biases remained unchanged - such as India's age-old affinity for lighter skin.

Mr Khadilkar told the BBC that when the researchers used a fill-in-the blank exercise to ask: "A beautiful woman should have [BLANK] skin," the predictive text was consistently 'fair'. Hollywood subtitles returned similar results, though the bias was less pronounced.

"The study shows that beauty is a close neighbour of fairness in Bollywood at all times".

Fans revere stars, pray for their wellbeing, even build temples to them and donate blood in their name

The research also revealed a subtle caste bias - an analysis of surnames of doctors showed "a visible upper-caste Hindu bias" - and showed that representation of other religions had increased in recent years but that of Muslims - India's largest minority - remained less than the community's population share.

Shubhra Gupta, film critic and author of Fifty Films That Changed Bollywood, says that's because "most creators are catering to the upper caste, upper class and dominant religion because they are from the same group".

Ms Gupta, who routinely takes apart "regressive, misogynistic and patriarchal films" in her columns in the Indian Express newspaper, says the big hero in Bollywood almost always has a Hindu name and the portrayal of Muslims is limited and full of clichés.

In India, audiences go to the cinema to watch spectacles, song and dance entertainments, so filmmakers stick to the tried and tested template.

BBC News's two minute guide to 100 years of Indian cinema

Every once in a while, she says, there's one significant film that would surprise you, but then there would be 10 others that would go back to the cliché.

"The industry," she says, "is most risk-averse. The filmmakers say we are giving what the audiences want, they are worried what would happen if the fans turn their back on them?"

But Ms Gupta says "real change is possible" if we consider the popularity of the content that is being released on OTT platforms during the pandemic.

"It has taken a pandemic to show that the audiences are willing to look beyond stereotypes. And when the audiences say we have the power, we demand more, the filmmakers will have to make better films. Then Bollywood will have to change."

- Published22 September 2020

- Published8 August 2020

- Published29 September 2020

- Published20 August 2020