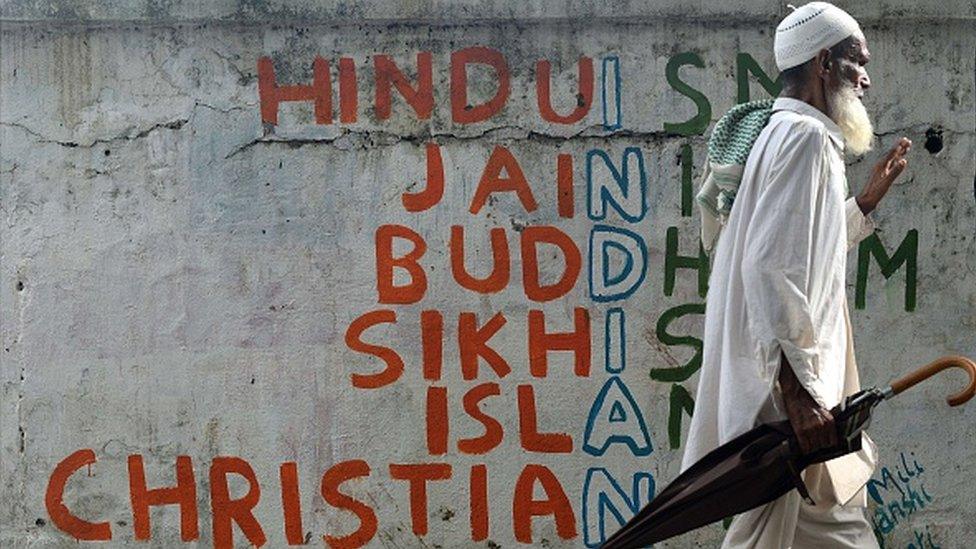

Pew survey: India is neither a melting pot nor a salad bowl

- Published

Hindus make up 80% of India's population

For long, societies have been described as melting pots and salad bowls.

The first encourage immigrants to fuse into a dominant culture; in the second, immigrants retain their own characteristics while integrating into a new society.

India is apparently neither, according to a new study, external by US-based Pew Research Center. The non-profit fact tank has released this comprehensive survey on religion in India after talking to some 30,000 people in 17 languages. Hindus make up 80% of the population, while Muslims comprise 14%.

When it comes to religion, the study finds that Indians of all faiths support, at once, religious tolerance and religious segregation.

The majority (84%) say that "respect" for other religions is an important part of their identity and to being truly Indian.

Yet a substantial number of them do not want neighbours who belong to another religion, and are opposed to interfaith and inter-caste marriages. They also prefer making friends within their own religious community.

"This points to a unique understanding of plurality of Indian society - it is more like a thali (an Indian meal comprising a selection of separate dishes served on a platter), rather than a melting pot," says Neha Sahgal, one of the lead authors of the study.

The religious life of Indians - key findings

64% Hindus say it is very important to be Hindu to be 'truly Indian'

Roughly two-thirds of Hindus want to prevent interfaith marriages of Hindu women or men; even larger shares of Muslims feel similarly

36% Hindus do not want a Muslim as a neighbour

53% of adults say religious diversity benefits India

97% Indians say they believe in God and roughly 80% people in most religious groups say they are absolutely certain that God exists

(Source: Religion in India, Pew Research Center)

Many scholars believe , externalIndia's founding fathers wanted a society which was more a salad bowl, where the national identity recognised and accommodated a diverse group of citizens.

So has this dream floundered and has India turned out to be a complex republic, a patchwork quilt of people, religions and cultures where people live together, but separately?

It is difficult to say. Despite the strongly held desire for religious segregation, Indians share a lot of beliefs. For instance, most Hindus (81%) believe the holy Ganges river has the power to purify. But so do 66% of Jains (66%), a quarter of Muslims and a third of Christians.

Muslims are also just as likely as Hindus to say they believe in karma (77% each) - a belief that says actions have consequences. Some 54% of India's Christians also share the view.

"It is not uncommon to see seemingly contradictory viewpoints in public opinion," Jonathan Evans, the second lead author of the study told me.

In West Europe, for example, a 2019 Pew study , externalfound that Christians - whether they attended church regularly or not - were more likely than people with no religious identity to have negative views of religious minorities and immigrants.

India is a deeply religious country

The results led many to wonder how this fitted the Christian doctrine of "to love thy neighbour" and actions of West European churches to actively resettle refugees from the Middle East. The survey outlined the strong connections between Christian identity and attitudes on religious minorities and immigrants.

At the same time, some of the findings in India are strikingly different too. For example, only 58% of the respondents said they would be willing to accept a Muslim neighbour.

A much larger majority of respondents in Italy (65%), UK (78%), France (85%) and US (89%) in a Pew study said they would be willing to accept Muslims as neighbours, external, although none of these countries were free of anti-Muslim sentiments. And across Western Europe, people were split on Islam's compatibility with their country's culture and values.

In India, scholars said, religious segregation was closely tied to the fault lines of national identity and politics.

Not surprisingly, the survey found that Hindus who voted for Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) said that being Hindu and speaking Hindi - one of the many main languages spoken in India - were important to be truly Indian. They were also more likely to be wary of people of other faiths as neighbours and interfaith marriages.

Is that leading to discrimination against the minorities?

More than 40 people died when clashes broke out between Hindus and Muslims in Delhi in 2019

According to the survey, about a quarter of followers of any of the major faiths said they had faced a lot of discrimination. Separately, one in five Muslims living in northern India - largely ruled by Mr Modi's Hindu nationalist party - said they had faced religious discrimination.

More worryingly, a majority (65%) of Indians - Hindus and Muslims almost equally - said religious violence was a "very big problem". Only corruption, crime and violence against women ranked higher as issues of concern.

Surprisingly, only 20% believed discrimination on the basis of caste was widespread. "It is quite possible for an exclusionary society to think it is not discriminating. We have not even progressed from exclusion to discrimination," noted Pratap Bhanu Mehta, external, a leading scholar.

So what does this survey - the largest conducted by Pew outside US - tell us about India?

Analysts like Prof Mehta believe it reveals a religious nation which is committed to diversity, but also an exclusionary one with dwindling support for individual freedom and an increasing commitment to Hindu politics.

More broadly, according to Hilal Ahmed, a scholar on political Islam, the survey reinforces the fact that India is a "conservative society in a democratic framework".

What happens when a Hindu and Muslim YouTuber meet?

Read more by Soutik Biswas