Prashant Kishor: How to win elections and influence people

- Published

Mr Kishor helped political parties win eight of the nine elections he was hired for

Prashant Kishore is not an ordinary political consultant.

According to his telling, he rarely watches news on TV and he doesn't read newspapers. He doesn't write emails, or take notes, and he hasn't used a laptop in a decade. The only gadget he uses is his phone, he told me. Mr Kishor has posted 86 tweets in three years on Twitter, where he has half a million followers.

"I am not a believer in work-life balance and have literally no interests outside my work," he said.

Mr Kishor is India's best-known political consultant and strategist, though he dislikes the description. He is seen as a high-profile handler of politicians and an astute tactician who has perfected the art of winning elections and influencing people.

Since 2011, Mr Kishor and his political consultancy firm have struck success with eight of nine elections in which they have run campaigns for different parties. He has had offers from Disney, Netflix and even Bollywood's Shah Rukh Khan for biopics - all of which he has refused.

Mr Kishor has successfully advised politicians of all hues - from BJP's Narendra Modi in his sprint to power in 2014 to arch-rival Mamata Banerjee of regional Trinamul Congress party in her sensational third-term win in May against a resurgent BJP. His supporters call Mr Kishor a man with a Midas touch; his critics say he chooses his clients carefully, based on their chances of winning.

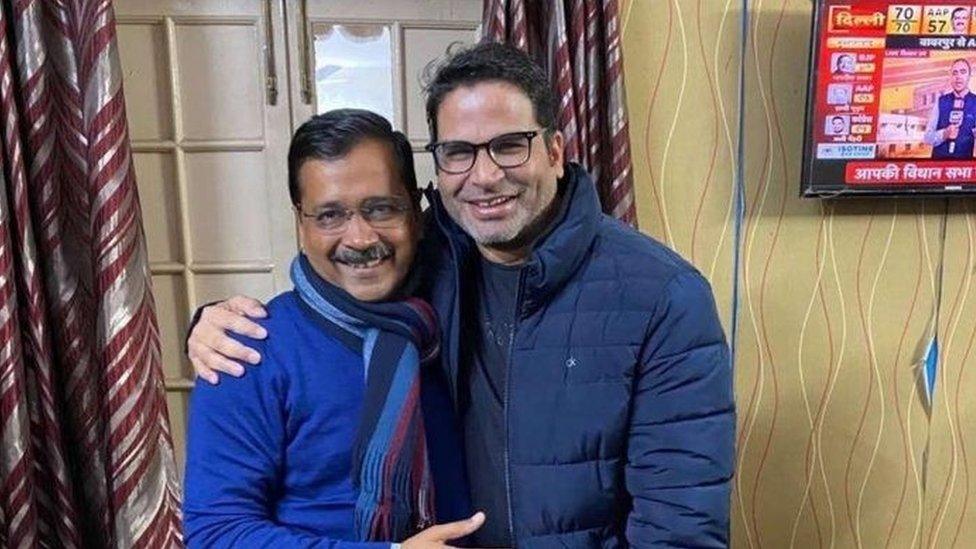

Mr Kishor helped run the campaign for Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal

In May, Mr Kishor, 44, announced he'd had enough with the job he was doing. "I am quitting this space," he said. "I want to do something else."

But in recent weeks, he has been in the headlines again. Meetings with key opposition politicians, including Congress party leader Rahul Gandhi, have sparked reports about the canny consultant trying to help cobble an alliance against Mr Modi's Bharatitya Janata Party (BJP); or even joining Mr Gandhi's party to shore up its flagging fortunes.

All this is speculation, Mr Kishor said.

"I am definitely not going to do what I was doing earlier. I have a few options but I haven't made a decision. It is quite possible that I end up doing something which has got nothing to do with politics. As soon as I take a decision I will formally share it," he said.

With general elections three years away, India's opposition parties appear to be struggling to mount a robust challenge to Mr Modi. Mr Kishor believes the BJP is not quite the supremely powerful party it's made out to be, and there is "always space for a party, existing or new, to mount a challenge on its own and in combination with other parties".

The Congress has seen a steep decline - it's share of votes and seats falling since the mid-1980s. In 2019, it picked up 20% of the popular vote, won a paltry 52 seats and lost its second consecutive election. But the party still has about 100 MPs in parliament and 880 state legislators. It remains the largest opposition bloc to take on BJP.

"I am nobody to comment about what is wrong with Congress. I can only say that the problems of the party are much deeper than what appears in their electoral performance of last decade. They are more structural," he said.

Mr Kishor has worked with politicians of all hues

Floating a new federal party is easier said than done. Cobbling together a third opposition alliance is neither "doable or sustainable" because a rag-tag coalition does not bring, which has not already been tested and rejected by voters, to the table," Mr Kishor said.

Yet he believes that the BJP - which will be seeking a third term in 2024 - is not invincible. "There are options and enough examples to show that with right strategy and efforts they could be defeated," he said.

Mr Kishor said winning parties in India, no matter how popular, usually don't win more than 40-45% of the popular vote. In 2019, BJP picked up 38% of the vote and won more than 300 seats.

The BJP, he says, has not be able to win more than a fifth of the 200-odd seats in seven states in eastern and southern India as regional parties have been able to effectively prevent the party from making inroads.

The remaining 340-odd seats are in the north and the west of the country, where the BJP is influential. A challenger to the BJP pick up around 150 seats in these parts, reducing BJP's margin, Mr Kishor said.

The way Mr Kishor works offers a glimpse into how political consultancy works in a country like India. His firm Indian Political Action Committee (IPAC) - which has up to 4,000 people working during campaigns - embeds itself in the party they are hired to work for.

Mr Kishor most recently helped West Bengal Mamata Banerjee win

"We act as a force multiplier helping the party to do whatever is required for them to do well in the elections," Mr Kishor said.

"We make some difference, but it is difficult to quantify how much exactly."

Mr Kishor's takeaways from a decade in Indian electoral politics: high turnouts at campaign meetings are insignificant to poll outcomes; entry barriers to politics are higher as elections become more expensive; and a politics and society that are getting increasingly polarised.

And what informs the voting choices of more than 800 million Indians?

"Delivery of welfare benefits, identity, empowerment, access, many intangibles. I could never hazard a guess," Mr Kishor said.

"I never try to second guess voters. I just try to develop systems to find out what people are saying. And we are always surprised and humbled by the new information that comes from listening."

In 2015, his team went to 40,000 villages in Bihar, India's poorest state and Mr Kishor's birthplace, to find out more about their problems.

"The number one issue was lack of drainage," he said. They found a fifth of the police complaints in police stations were related to fights over bad drainage.

In Bengal last year, Mr Kishor helped set up a helpline to record people's complaints. Seven million people dialled in. The majority of them complained of delayed delivery or corruption over caste or affirmative action certificates, Mr Kishor said. Acting on the complaints, the government issued 2.6 million such certificates in six weeks.

Despite his successes, he thinks - curiously - that politics is not his strong suit. "I don't really understand it very well," he said. He strength lay instead in common sense, he said, and listening carefully. "And I love to work under pressure".

If you haven’t been paying much attention, here’s what you've missed.