1991 reforms: 'A long distance call was like an endurance sport'

- Published

India has more than a billion telephone subscribers

In the summer of 1981, a man who called himself a consultant turned up at a young woman's home in India's western city of Mumbai.

She was starting a small business and he said he could help her secure a new telephone connection for a bribe.

The process usually took up to two decades back then - a government-owned monopoly was the sole source of phone connections. By the mid-1980s, nearly a million people were waiting for a phone.

Before July 1991 - when historic reforms threw open the door to India's economy - such "consultants" roamed outside offices in the country, offering out-of-turn phone connections, driving licences and passports for a hefty premium.

Otherwise, Indians queued up for everything. They waited 10 years for a scooter and seven years for a car. A columnist wrote of how he had to "pull strings" to get milk powder for his first child.

In the case of the Mumbai woman, the consultant's fee was 15,000 rupees ($201; £145), nearly 15 times her monthly pay. He said it was so expensive because a part of this money would go to a federal minister's family.

"They will get you the connection and take a bribe," he said. The woman, who did not want to be identified, dipped into her savings and paid up. She got a new connection in two weeks.

Indians waited up to 10 years to buy a car

The reforms in 1991 liberated consumers from "shoddy goods and services, unaffordable prices, unaccountable suppliers and trying shopping environments," said Rama Bijapurkar, a management consultant.

A crisis triggered the sweeping changes: foreign exchange reserves had dwindled, public debt had ballooned and inflation was in double digits. India, in other words, was nearly bankrupt.

So, the government reversed decades of socialism overnight: it got rid of crippling licenses, allowed private companies and foreign investors into the market, devalued the rupee and reduced import duties.

India's economy - now $2.66tn - has since grown by over 10 times. At $2,097, annual average incomes are up by nearly seven times. More than 270 million Indians were lifted out of extreme poverty between 2005 and 2016, according to the United Nations Development Programme.

Here are four ways in which the reforms transformed India.

'A long distance call was like an endurance sport'

Of 840 million Indians in 1991, only some five million had telephones.

Many telephone exchanges were half-a-century old. So, even if you were fortunate to own a phone, it often didn't work. Angry subscribers put out adverts in papers announcing funeral services for their "dead" phones.

When "lines crossed", people spent hours eavesdropping on others' conversations.

Indian author Shobha De speaks on the phone in her home in 1993

Making long distance calls was like an "endurance sport," said Santosh Desai, a columnist.

You booked a call in the morning, which sometimes got connected in the evening - even when it did, you could barely hear anything. "There was so much screaming and shouting that half of the conversation was incomprehensible," Mr Desai said.

I knew by heart the portfolio of a neighbour who bellowed out to a broker what stocks he would buy and sell on a long-distance call every morning.

Overbilling was rife: one minister complained that he had been billed 18,000 rupees when he was out of the country.

Today India has more than a billion mobile phone subscribers alone.

Local calls, text messages and internet data are among the cheapest in the world; and incoming calls are free. Smartphones are available for as cheap as 5,000 rupees.

'A visit to the bank was like going to the dentist'

Economist Omkar Goswami recalled the "sheer tedium" of banking in the early 1990s.

Stern-looking clerks sat behind steel grills and entered transactions in fat ledgers.

When you deposited a cheque, they gave you a brass token with a number.

1991 reforms: The year that transformed India

Then you waited and waited for your grubby, stapled wad of notes. "The cashier would then holler your number, and you would rush to get the money and escape," Dr Goswami recounted.

A visit to the bank in the 1990s was "like going to the dentist," Mr Desai said.

Today, Indians use more than 820 million debit cards and 57 million credit cards to withdraw cash from more than 200,000 ATMs across the country.

Cashless payments have soared too: in 2019, mobile payments rose 163% to $286bn, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The number of bank branches has grown more than two-fold in 30 years - banks are friendlier places now.

'How flights become a health hazard'

This was the headline of an irate magazine piece on flying in India in 1988.

It wasn't easy to get a seat on the government-owned Indian Airlines, the only domestic carrier at the time.

Airports were shabby, queues long and check-in staff gruff. Flights were often cancelled or delayed because of flash strikes. Fights broke out and passengers sometimes ran to the tarmac and staged protests under an aircraft.

Indian Airlines was the only domestic carrier for decades

In-flight meals were paltry and boring. "I am sick of eating idlis [a steamed rice cake] on every early morning flight," a newspaper quoted a businessman as saying in the 1980s.

But the reforms prised open the door for private players.

By 2015, India's domestic aviation market had grown more than ten-fold with 13 private airlines. Some 125 million passengers flew within India in 2018; another 47 million flew abroad.

'A choice between news and animal husbandry'

TV came to India in 1959 with one-hour programmes on education twice a week. Daily transmissions began six years later with four hours of programming, mostly made up of news bulletins. All of this was broadcast on a single state-owned channel.

For more than three decades, Indians endured Doordarshan. The choice, according to a leading businessman, was between the news and a "stimulating programme on animal husbandry".

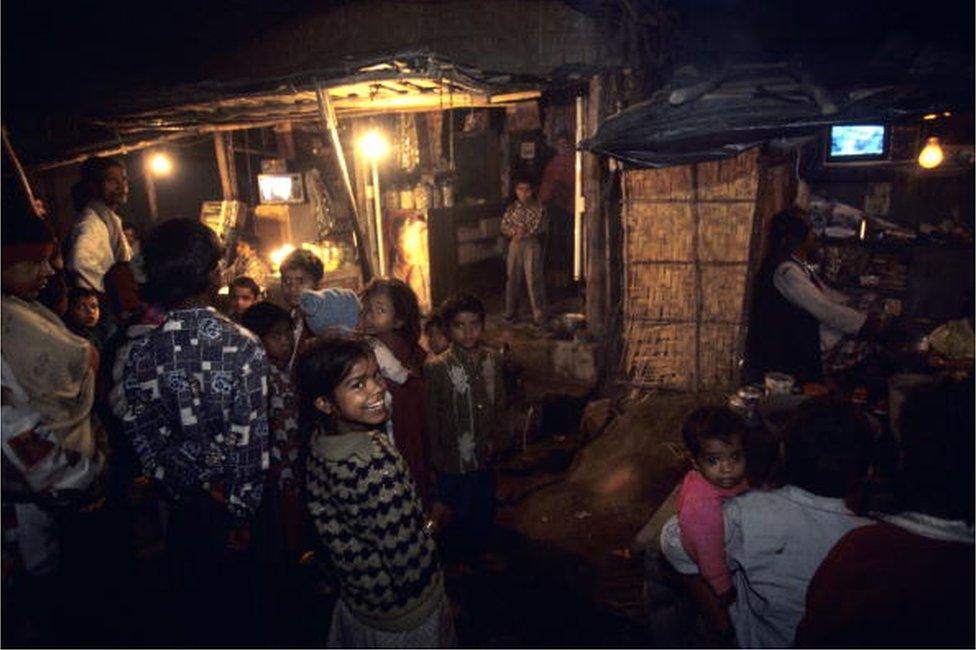

People in the streets watch TV in a Delhi slum in 1999

When Doordarshan made an exception and broadcast live bits of the Live Aid charity concert in 1985, there was a prolonged power outage in my city and I missed the show. In an economy of all-round scarcity, entertainment, even when available, was elusive.

Indian TV subscriptions now offer 926 private channels, including more than 400 news channels in 15 languages, to more than hundreds of millions of households.

Thirty years of reform, according to business tycoon Mukesh Ambani, has transformed India from "an economy of scarcity to an economy of sufficiency". India is now the world's fifth largest economy.

But grave challenges remain. Growth has slowed sharply in the last few years, and the pandemic has battered an already ailing economy. India still ranks low on global ease of doing business indexes.

Manufacturing has stagnated and major reforms are pending in land, power and labour. State-owned companies continue to burn taxpayers' money. Bank deposits have swelled, but debt-ridden banks are loathe to lend, leading to low private investment .And there aren't enough jobs for the tens of millions of youngsters entering the workforce every year.

Consumers, Ms Bijapurkar said, have been on a "winning spree" since 1991.

"The pandemic has put the breaks on incomes and consumption. But the desire to consume has spread and increased. There is no going back."

- Published22 June 2021

- Published10 August 2020