India teachers’ fight for period leave gathers steam

- Published

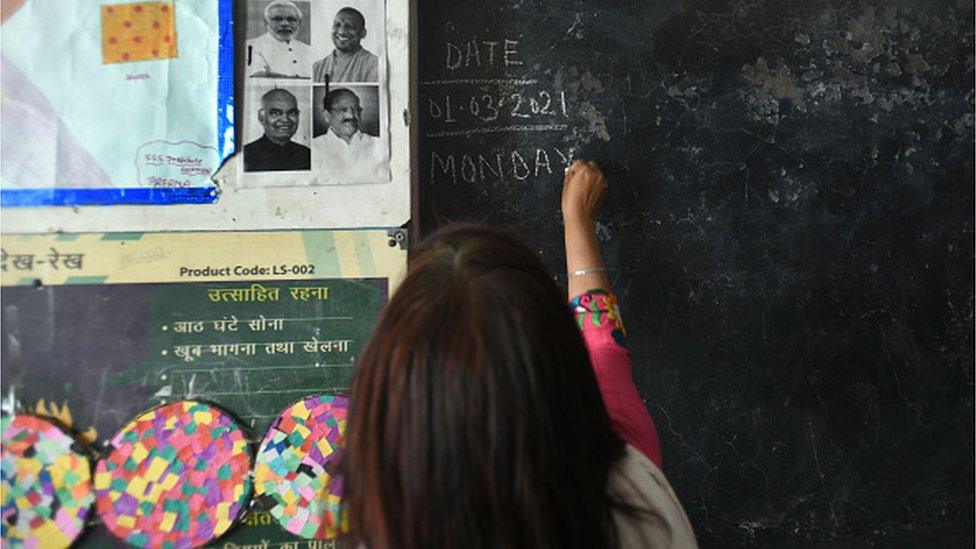

Government school teachers in Uttar Pradesh are demanding period leave

Female teachers in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh have started a campaign seeking three days of menstrual leave every month.

Many teachers say they have to travel long distances to areas that are not well connected by public transport and that filthy toilets at schools - which are generally unusable - add to their misery during periods.

The campaign was launched last month and has been gathering steam. It's led by the Uttar Pradesh Mahila Shikshak Sangh, an association of female teachers in the state that represents more than 200,000 female teaching staff working in the 168,000 government-run schools.

Sulochana Maurya, principal of a school in Barabanki district and president of the association, says more than 70% female staff are posted in villages.

"It's well known that menstruating women need rest as many experience physical discomfort and emotional agony and travelling 30-60kms to reach schools in remote rural areas can be especially taxing," Ms Maurya told the BBC.

"In some areas, unserviced by regular public transport, they have to hitch a ride, sometimes travel the last mile on tractors or bullock carts," she added.

A teacher - she does not want to be named - at a rural school, about 200km (124 miles) from the state capital, Lucknow, says teachers use school toilets only in an emergency.

"There are six toilets in our school but on most days all of them are dirty. They are not cleaned every day and with hundreds of students using them, they are unusable," she says.

"For the local teachers it's still okay, they can go home if they need to use the bathroom, but for those who come from other villages or distant places, it's a big problem."

Ms Maurya says many female students also don't come to school when they get periods. "At the moment, we are fighting for leave for teachers. Later, it can be extended to students too," she says.

More than 200,000 female teaching staff work in the 168,000 government-run schools in Uttar Pradesh

The concept of period leave is not new in India. Over the past few years, several private companies, such as digital entertainment firm Culture Machine, Tata Steel and food delivery app Zomato, have announced period leave for their female employees.

In the neighbouring state of Bihar, female government employees have been able to take "two days of special leave every month for biological reasons" for the past 30 years.

"So why can't Uttar Pradesh do it too?" asks Ms Maurya. "We are all citizens of one country so why have different rules for different states?"

Ms Maurya and members of the association have submitted their demand to the state women's commission, held a day-long Twitter campaign and are lobbying ministers, legislators and people's representatives. But a government spokesman told the BBC that they are yet to consider the demand.

The teachers' fight has once again put the spotlight on whether period leave helps.

It's a topic that has long polarised opinion and led to a passionate debate around whether it's a progressive move or just encourages stereotypes that women are weaker and unfit for the work space.

Many women say it helps them during painful periods, but others argue that it could actually be detrimental to women themselves as employers would use it as an excuse to hire fewer women.

Tanya Mahajan of the Menstrual Health Alliance of India (MHAI), a network of NGOs that works to create awareness about menstruation, says period leave makes it easier, especially for women who do have painful periods, as they can take a day off.

But in the workspace, she says, many women still hesitate to ask for period leave, especially if the boss happens to be male.

Many Indian women don't have access to sanitary pads or clean public toilets

That's because in India, periods have long been taboo and menstruating women are considered impure and face widespread discrimination.

Excluded from social and religious events, they are denied entry into temples and shrines and even kept out of kitchens. In some tribal communities in western India, they are banished to a period hut on the outskirts of the village on the edge of the forest.

Increasingly, urban, educated women are challenging these regressive ideas, but conversations around menstruation are still largely held in hushed tones.

According to one study, 23 million girls drop out from school annually as they hit puberty because of a lack of menstrual hygiene facilities, including access to sanitary napkins or clean toilets at school.

Ms Mahajan says giving period leave is, at best, a half measure. What is important is to have open conversations about menstruation.

"But are these conversation happening? Are offices and schools providing better wash facilities for women? Just changing policy doesn't make much difference unless it's followed up with action."

Using comics to combat India's menstruation taboos