Covid-19: The Indian children who have forgotten how to read and write

- Published

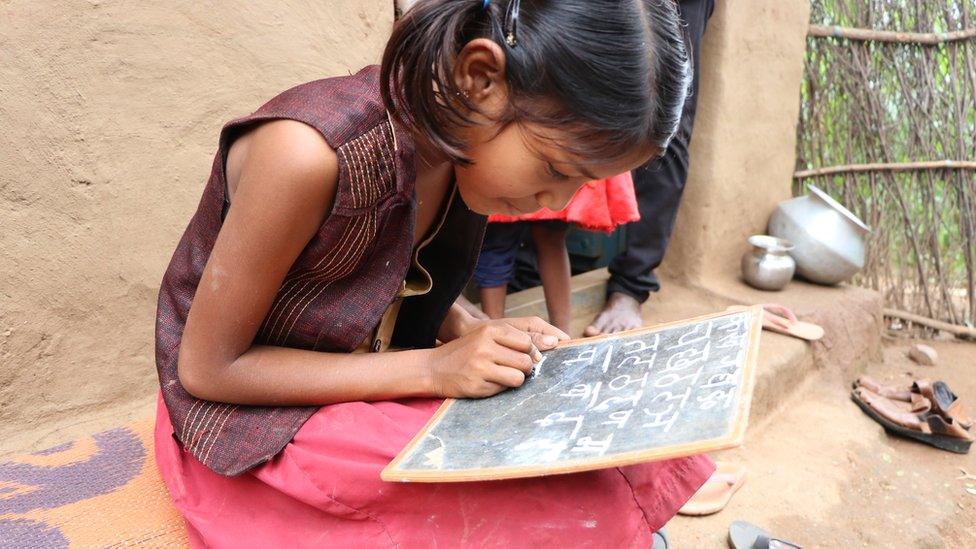

Radhika, 10, struggles to write the alphabet after 17 months of being out of school

Radhika Kumari holds her chalk with determination, almost willing the letters out of her mind onto the black slate.

But they tumble out slowly and she misidentifies many of them.

Radhika is trying to write the Hindi alphabet, a simple task for most 10-year olds. But, she says, she is struggling because it has been 17 months since she attended a class, online or offline.

Like everywhere else in India, schools have remained shut since March last year when the country went into lockdown to curb the spread of Covid-19.

Affluent private schools and their students switched to online classes seamlessly, but government-run schools have struggled. And their students - often with no laptops or smartphones and patchy access to the internet - have fallen behind.

In Jharkhand, a largely tribal, poor state where Radhika lives, this digital divide is stark. Her family is Dalit (formerly untouchable) and at the bottom of a deeply discriminatory Hindu caste system - as is most of the village.

There is no internet in her tiny village in Latehar district. Government or state-owned broadcasters have been running educational shows in some states but that's still inaccessible for many communities.

As schools started reopening in some states, economist Jean Dreze met Radhika and 35 other children in her village to assess learning loss in underprivileged communities. The survey took into account learning materials and extra classes, teacher visits, online learning and parents' education level among other things.

Radhika's primary school has offered no offline classes through the pandemic year

"It was really shocking to find that out of 36 children enrolled at the primary level, 30 were not able to read a single word," Mr Dreze said.

He added that the survey found that most primary schoolchildren had started to fall behind in reading and writing and had almost no access to learning materials.

"Hindi and English were my favourite subjects in school," Radhika says. There is little she remembers of either language now.

She was finishing class two at the local government-run primary school when Covid struck. She has now progressed to class four despite not having access to learning tools throughout the pandemic year.

It's compulsory under India's education laws for schools to keep passing enrolled children until class five. The aim was to relieve pressure on children while providing a supportive learning environment. Schools have followed the rule this year despite the disruption in learning for so many students.

Radhika's neighbour, seven-year-old Vinita Kumari, is equally impacted. Her father Madan Singh gets angry when she is unable to read or write, but with no formal training in the past year, she is struggling.

Pointing to her brand new books, he says he has no time to help her as he has to go out to earn a living. In this tribal village, most parents are unlettered and unable to help their young children study at home. So no school amounts to no learning at all.

Non-profits have sponsored open-air classes in some places to bring children back to school

Mr Dreze fears this can lead to younger children dropping out of school.

"Once you are able to read and write and you have reached higher levels, then you could fall behind a little bit but you'd still be able to continue progressing, and once you are able to read and write you can educate yourself quite a lot," he said.

"But if you've not learnt the basics and you are now left behind because you have been promoted to the next class, and you are actually below that, then it is as good as dropping out."

Mr Dreze and the three other economists he is working with plan to survey some 1,500 children in eight other states - Assam, Maharashtra, Odisha (formerly Orissa), Delhi, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. Volunteers will go door-to-door interviewing children between five and 14 years to assess their literacy rates compared to the 2011 census.

The pandemic has also widened the gender gap in learning. Some families can afford to pay for after-school classes, but most choose to send only their sons.

Radhika's brother, Vishnu, is a year younger but thanks to after-school classes he is far ahead of her in reading, writing and comprehension. Radhika is the youngest of five sisters, and none of them have attended any classes - online, offline or after school - in the past year.

"Vishnu's extra classes cost 250 rupees ($3.4; £2.4) every month," said the children's mother, Kunti Devi. "We do not have enough money to pay for his six sisters too."

Vishnu is younger than Radhika but often reads to her

This isn't unique. Many Indian parents choose to invest in their son's education because they hope to be supported by him when they grow old - daughters, on the other hand, are wedded into another family and leave home.

Data shows that poor parents are more likely to enrol their daughters in government-run free schools, while saving up to send their sons to cheap private schools.

"Almost unconsciously, girls like Radhika will start believing that there are things that she may want but her younger brother will get - she internalises it, her confidence levels, her sense of self-worth, all get impacted," said Samyukta Subramanian, who leads the early education programme at Pratham, one of India's biggest education non-profits.

Pratham's last Annual State of Education Report (ASER) found that during the week they did the survey by phone - in October 2020 - two-thirds of the children surveyed had received no learning materials or activities.

Ms Subramanian suggested that as schools reopen, teachers should spend time with children in fun group activities to assess their learning levels without putting additional pressure on them.

"Classroom education will have to be tailored to where the child is on their learning curve, else many of these children will just not be able to cope," she added.

Radhika's eyes light up at the thought of going back to school.

She said she has missed "playing and studying" the most - in that order.

"I will open the locked door and finally sit at my desk."

'I don't want to spend my life on the streets' - Asma Shaikh, 17, has big dreams. But the pandemic has brought new challenges.