Malkhan Singh: The surrender of India's bandit king

- Published

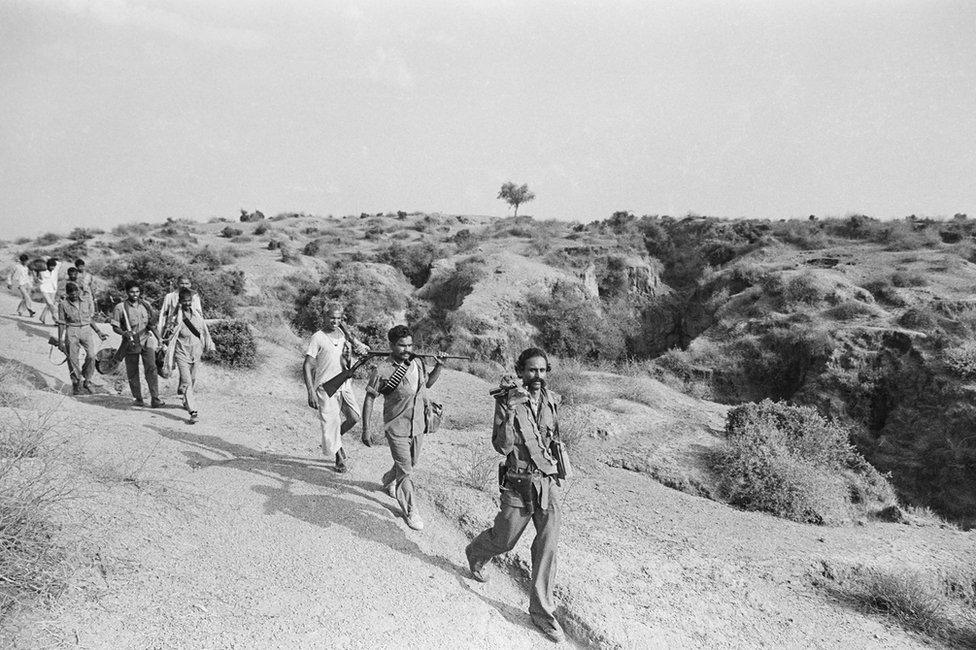

Malkhan Singh (sitting at front, centre) and his much-feared gang in his home village before surrendering

In the early 1980s, Indian photographer Prashant Panjiar trekked across the arid badlands of central India, chronicling the lives of the country's fabled bandits.

Most of the bandits lived and operated from Madhya Pradesh state's Chambal region, which Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Paul Salopek described as a "no-go zone of lumpy hills and silty rivers infested with thugs, robbers, murderers, gangsters - with infamous highwaymen called dacoits."

After months of trying, Panjiar and two fellow journalists managed to meet Malkhan Singh, popularly known as India's "bandit king", in Chambal in May 1982.

Bandits were also operating with impunity in the neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh: a year ago, Phoolan Devi, a female bandit, had risen to notoriety when she had 22 upper-caste Hindu men massacred on Valentine's Day to avenge her gang-rape.

But in Chambal, Malkhan Singh and his gang were the most feared. They travelled by foot and lived in makeshift camps in the ravines - deep and narrow gorges with steep sides.

At its peak during a 13-year-long reign, Singh's gang boasted up to 100 men - he had been crowned the "bandit king" by rivals. By 1982, police had registered 94 cases against the gang, including for dacoity (banditry), kidnapping and murder.

Singh himself, according to reports, had a reward of 70,000 rupees for his capture. Translated at today's rate, the reward was just over $900, but in the day it was worth almost $8,000 and a pretty big sum. The government also started sending out feelers to him to give up arms.

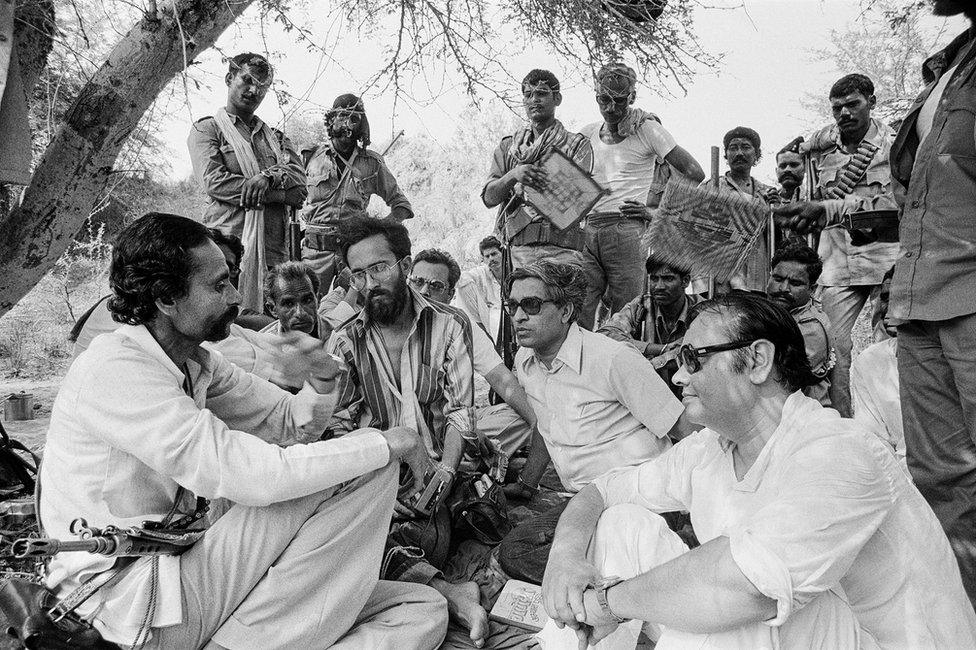

In the blistering summer of 1982, Panjiar and his colleagues Kalyan Mukherjee and Brijraj Singh found themselves at the centre of negotiations between the Congress-led government of Madhya Pradesh and Singh's gang for the latter's surrender. They developed a contact to meet Singh.

"I got to spend a few days with the gang. I was happy to be a 'hostage' - their guarantee against betrayal - as long as I was getting my pictures," Panjiar says.

Malkhan Singh's gang moves to the outskirts of a village that was declared a safe haven for surrender

He first met the gang on a moonless night in Chambal.

Panjiar remembers him as a tall and wiry man with a handlebar moustache, who was quite reserved. He carried a Belgian-made rifle.

"He was a man of few words, but an egotist and commanded respect."

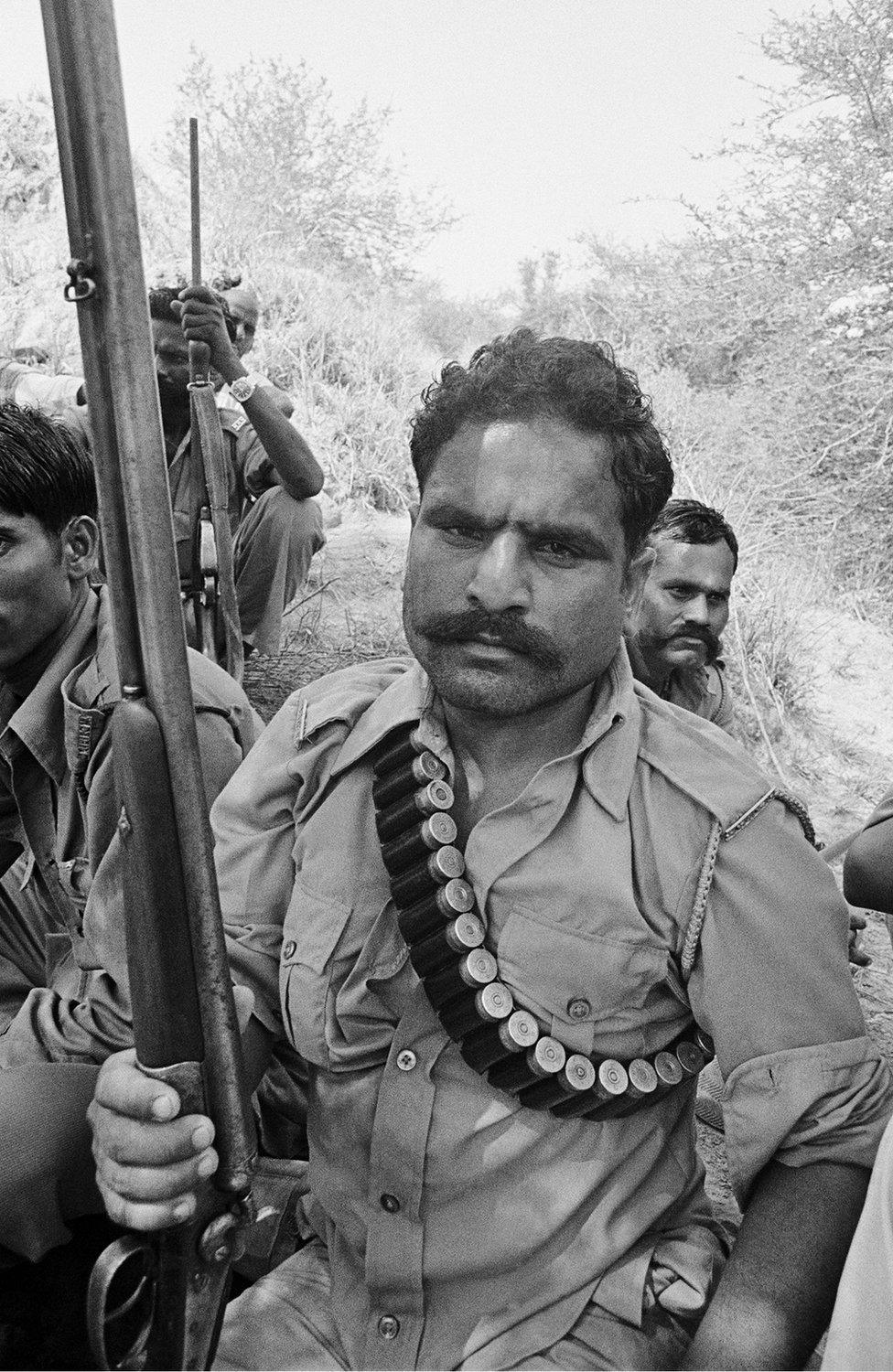

The gang, which was then about two-dozen-strong, moved from one location to another at night, carrying their sparse belongings - bedrolls, weapons, some tarp for protection from rain and simple rations. They slept in the open. One member, Panjiar remembers, carried an AK-47; others carried carbines and rifles.

Panjiar says Singh was a "classic Chambal story - a young lower-caste man who said he took up the gun for self-honour and self-protection and to seek vengeance against his tormentor, an upper-caste man."

Over nearly a week, Panjiar used his Pentax and a borrowed Nikon camera to shoot rolls of film of the gang. Some of these rare pictures appear in his new book, That Which Is Unseen.

The gang members at their camp

Malkhan Singh met government officials before his surrender

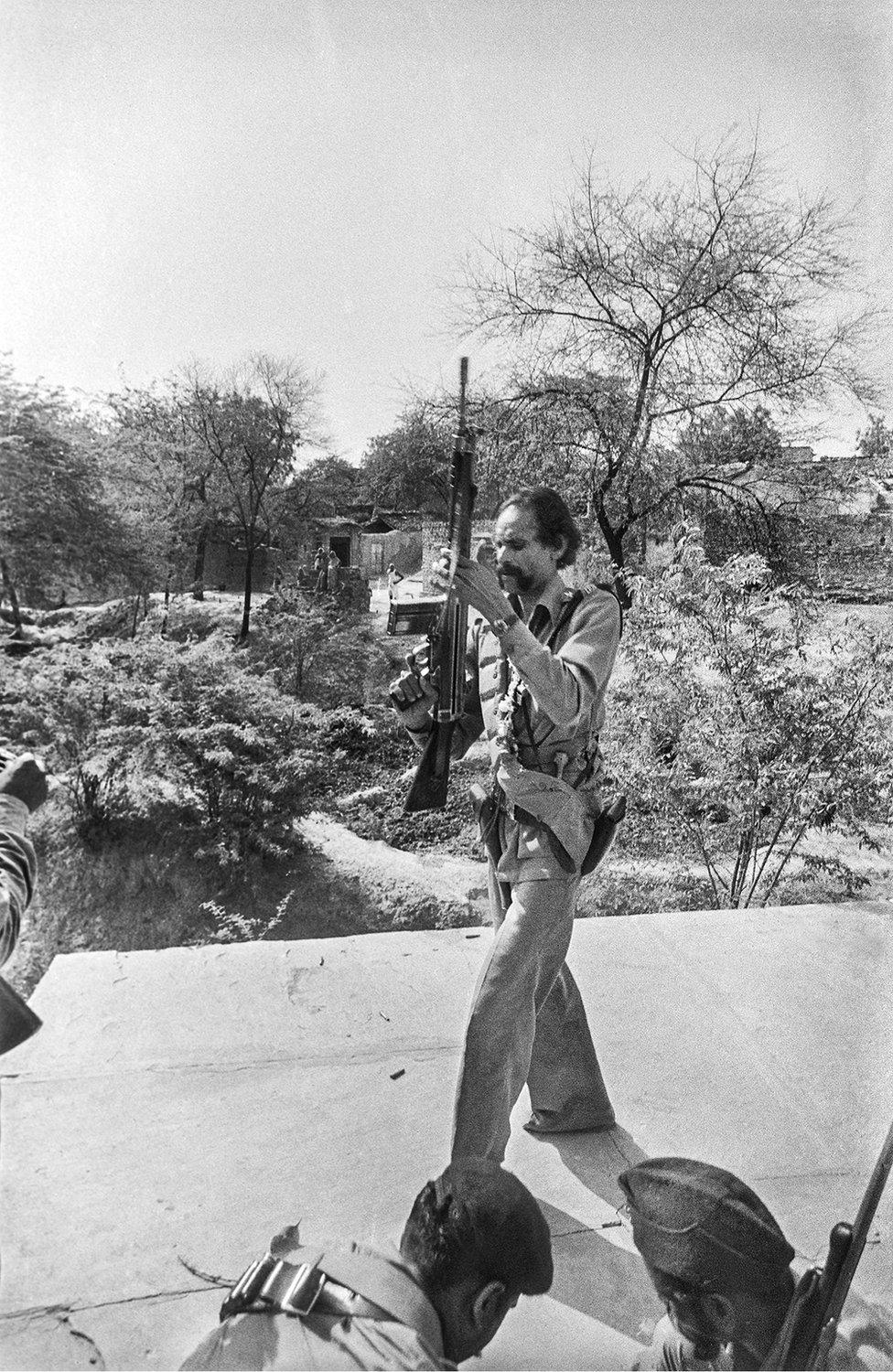

A gang member prays to his weapon and an image of a Hindu goddess before his surrender

Malkhan Singh before his surrender

The surrender finally happened in front of tens of thousands of people in June. Among other conditions, Singh had negotiated that none of his gang members could be handed the death penalty.

"He came like a conquering hero. Tall and lean, dressed in the uniform of the police he had fought hard in for years, dacoit king Malkhan Singh's farewell to arms in the town of Bhind in north Madhya Pradesh before an awed crowd of 30,000 had all the trappings of a Roman triumph," reported India Today, external magazine.

Singh had a dry sense of humour, Panjiar remembers. After his surrender, journalists pestered him with a stock question in Hindi: "Aap ko kaisa lag raha hai? (How are you feeling now?)" Singh would repeat the same line when he met Panjiar and his colleagues.

Eventually, Malkhan and his gang members were convicted for some of the crimes they'd been charged with, and were sent to an "open jail" in the state. Singh spent a few years in prison.

Now 78, he has pursued a career in politics, campaigning in recent years for the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

"I was not a dacoit. I was 'baagi' (rebel), who took up gun for self-honour and self-protection. I know who are real dacoits and also know how to deal with them," he said in 2019.

Prashant Panjiar is a leading Indian photographer and author, most recently, of That Which Is Unseen (Navajivan Trust)

- Published27 June 2021