Viewpoint: When Hindus and Muslims joined hands to riot

- Published

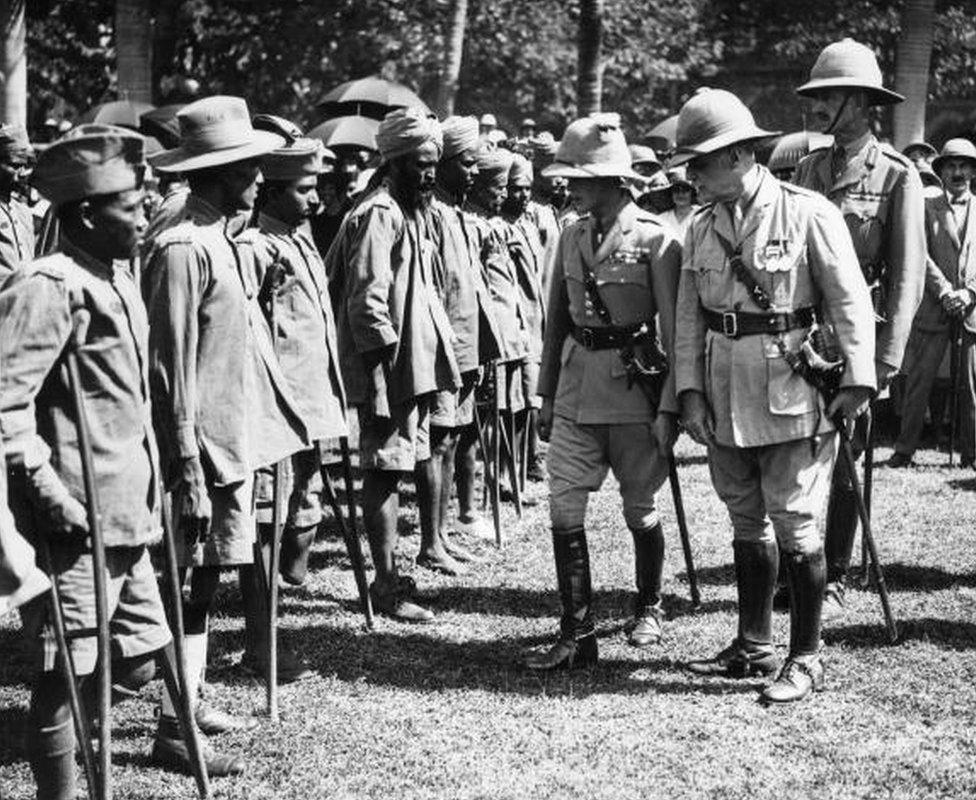

Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII, began a royal tour of the Indian empire in 1921

A hundred years ago, colonial Bombay (now Mumbai) was convulsed by one of the most unusual riots in Indian history. Hindus and Muslims fought together on one side, joining hands against other groups. Historian Dinyar Patel writes about the lessons that moment holds for today's India.

The riots of 1921 - or the so-called Prince of Wales Riots - are all but forgotten now in Mumbai. But, in these polarised times, history provides important lessons about religious intolerance and majoritarianism.

The violence that unfolded involved an Indian Independence hero, a future British monarch, and a tottering Ottoman sultan. It was fuelled by disparate ideologies and goals: swaraj (self-government), swadeshi (economic self-reliance), prohibition, and pan-Islamism.

In November 1921, the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII, began a spectacularly ill-timed royal tour of the Indian empire.

India was then in the grips of Mahatma Gandhi's non-cooperation movement, the biggest threat to British colonial rule since the rebellion in 1857, external.

Under the banner of "Hindu-Muslim unity", Gandhi had joined forces with the Khilafat movement, led by Indian Muslims. They worried that after the Ottoman Empire's defeat in World War One, Great Britain would depose its sultan, whom they regarded as the legitimate caliph of Islam.

While ushering in a remarkable moment of communal fraternity, Hindu-Muslim unity raised fears of majoritarianism among smaller minority groups: Christians, Sikhs, Parsis and Jews.

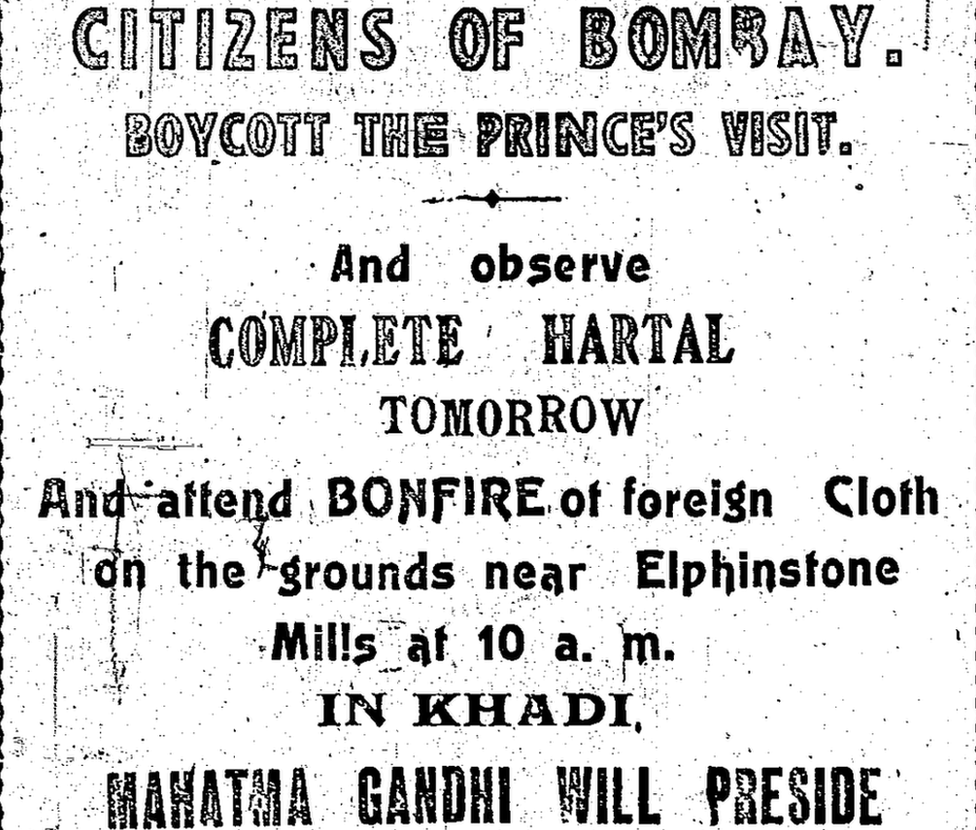

There were bonfires of foreign-made cloth, a symbol of Britain's economic imperialism in protest against the visit

Gandhi said they had nothing to fear. "The Hindu-Muslim entente does not mean that big communities should dominate small communities," he declared.

The Prince of Wales, for his part, naively hoped that his visit would rouse loyalist sentiments and take the steam out of Gandhi's movement. In response, the Indian National Congress resolved to welcome the prince to Bombay with a hartal or strike, and bonfires of foreign-made cloth, a symbol of Britain's economic imperialism.

On the morning of 17 November 1921, a significant number of Bombay's residents defied the strike and attended the prince's arrival by ship. Many of these well-wishers were Parsis, Jews and Anglo-Indians.

Despite Gandhi's directive to remain nonviolent, Congress and Khilafat volunteers reacted with rage. Homai Vyarawalla, who became India's first female photojournalist, was a young witness to these events.

When I interviewed her in 2008, she recalled Parsi schoolgirls staging garbas - a traditional dance - to welcome the Prince of Wales. But in the following days, Vyarawalla observed pitched battles on Bombay's streets. Rioters used the marble stops of soda bottles as lethal projectiles. They targeted Parsi-owned liquor stores, hurling stones and threatening to burn them down.

Gandhi had tried hard to include prohibition in the non-cooperation movement, urging Parsis, who had a disproportionately large stake in the liquor trade, to voluntarily close down these shops.

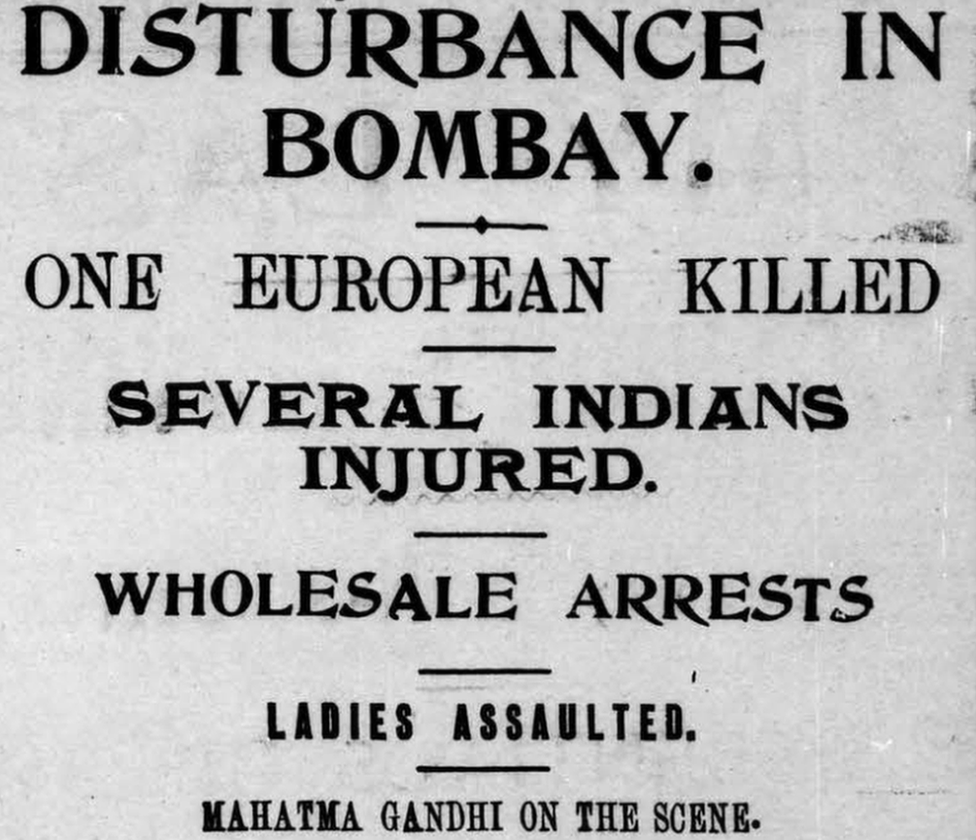

A newspaper headline of the riots in Bombay

As violence shook Bombay, Hindu and Muslim rioters singled out liquor stores as symbols of Parsi economic dominance and their resistance to nationalist politics. They threatened to burn down one Parsi residential building with a liquor store on its ground floor, relenting only when the store owner emptied his stock into the street gutter.

Parsis and Anglo-Indians were not simply innocent victims. Many of them joined the fracas, wielding lathis or bamboo sticks and guns. They assaulted individuals dressed in khadi, the homespun garb of Gandhians, and yelled "Down with the Gandhi caps". Congress-aligned Parsis or Christians could be targeted by both sides.

Gandhi swiftly reacted to the violence, bringing together leaders of various communities to broker peace.

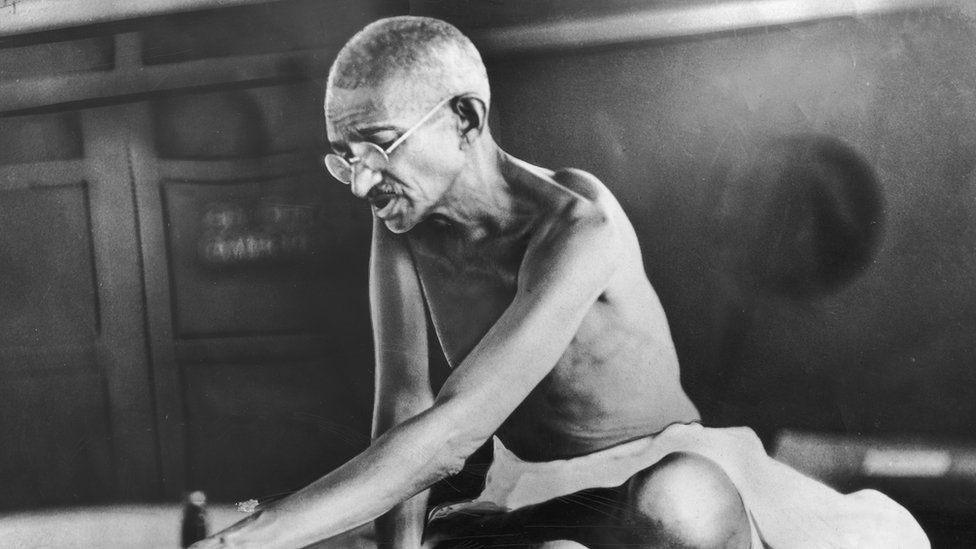

On 19 November, he launched his first-ever hunger strike against religious rioting, vowing to abstain from food or drink until the violence abated.

His tactics worked: by 22 November, Gandhi was able to break his fast, surrounded by Indians of various communities and political persuasions.

But the Prince of Wales Riots shook him to the core. "We have had a foretaste of swaraj," he declared with irony. He bitterly noted that the riots had validated smaller minorities' fears of violent majoritarianism.

And so, as Bombay recovered from the carnage, Gandhi feverishly worked to regain the trust of these minorities.

Gandhi launched his first-ever hunger strike against religious rioting in 1921

He instructed Congress and Khilafat volunteers on the importance of minority rights and worked out reparations. Majority communities, Gandhi declared, had a sworn responsibility to uphold minorities' welfare. At meetings and in Congress publications, he yielded significant political space to minority representatives, who voiced their misgivings about Gandhian tactics and their worries about majoritarian impulses.

Most remarkably, Gandhi steadily replaced the slogan of Hindu-Muslim unity with a new one: "Hindu-Muslim-Sikh-Parsi-Christian-Jew unity".

It was an unwieldy phrase, but it did the job, helping convince smaller minorities that they would have a place in independent India.

At least 58 people died in the riots, while over one in six liquor establishments in Bombay were attacked. For the Prince of Wales, the riots marked an ominous beginning to his tour. Elsewhere in India, he was greeted with strikes or threats of assassination.

But Gandhi's steadfast diplomacy is the reason the riots are now forgotten. He dissipated the spectre of majoritarianism, ensuring that the riots did not permanently scar Bombay.

Herein lie some lessons for today.

Communal violence, as the Prince of Wales Riots demonstrated, is largely a political construct.

It is not the product of ancient, unbridgeable religious differences. In 1921, the political mood impelled Hindus and Muslims to fight together against other communities. Only a few years later, after the collapse of the Congress-Khilafat alliance, Hindus and Muslims engaged in even bloodier skirmishes against one another.

There is another lesson. Majoritarianism is a fickle, unwieldy thing. Its underlying calculus can shift and fragment in unpredictable ways, just as it did on Bombay's streets in the 1920s.

Perhaps that is why Gandhi went to such lengths to foreswear majoritarianism, instead stressing tolerance of even the smallest of minorities.

A hundred years ago, he issued a prescient warning: if the majority unites today to oppress others, then "tomorrow the unity will break under the strain of cupidity or false religiosity".

Dinyar Patel is the author, most recently, of a biography of Dadabhai Naoroji