Bihar railways exam violence: 'We are graduates, we are hungry'

- Published

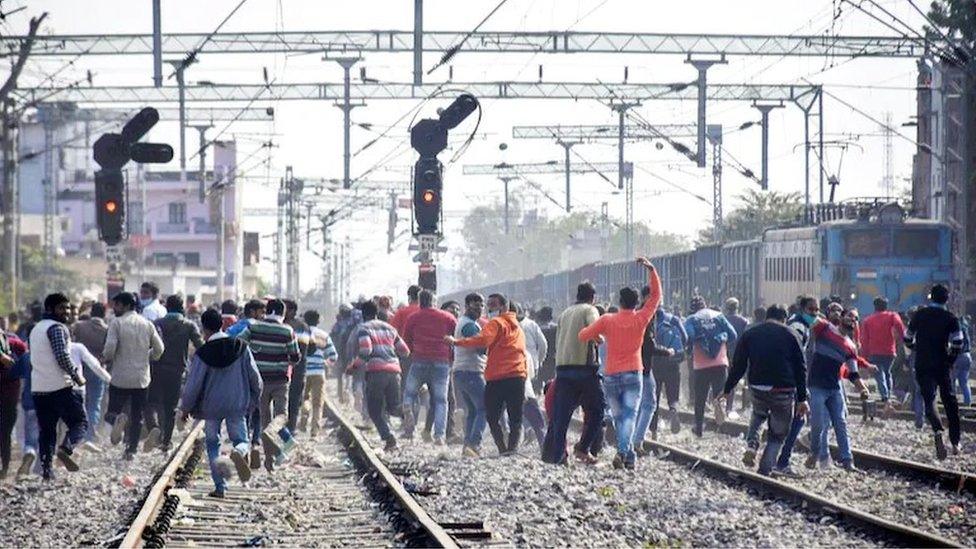

Protesters torched trains during this week's protests in Bihar

"We are graduates, we are jobless, we are hungry. Don't kick us in our stomachs," a young man in India's eastern state of Bihar told a colleague this week.

His anguish followed three days of rioting over jobs spread over a dozen districts in one of India's most backward states. More than 10 million aspirants had signed up for 35,000 jobs with the railways, India's largest employer.

Aspirants alleged that the hiring process was non-transparent and riddled with problems, including allowing those with higher qualifications to compete for jobs for less qualified candidates. Frustration led to anger and escalated to violence. Students allegedly stopped trains and set fire to coaches. Police fired in the air and baton-charged protesters. The railways suspended the hiring, and threatened aspirants with barring them from all railway exams in the future.

One newspaper said the protests were not merely about a lack of jobs, but the "toll that they were taking on the young". The protester who spoke to my colleague said he was the son of a farmer who had sold his land to get him educated. His mother would not buy medicines when she fell ill so that they had enough money to pay for his rent and private coaching classes in the city. He mocked Prime Minister Narendra Modi's remark in 2018 on how opening a small pakoda (a spiced fritter snack) kiosk also counted as a job. "Why are you asking graduates to fry pakodas?," he said.

In many ways, the young man's outburst - and the violent protests - shone a harsh spotlight on India's worsening job crisis. This week's job riots in Bihar and neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, many believe, should be a wake-up call for authorities - the two populous states account for a quarter of the jobless in India.

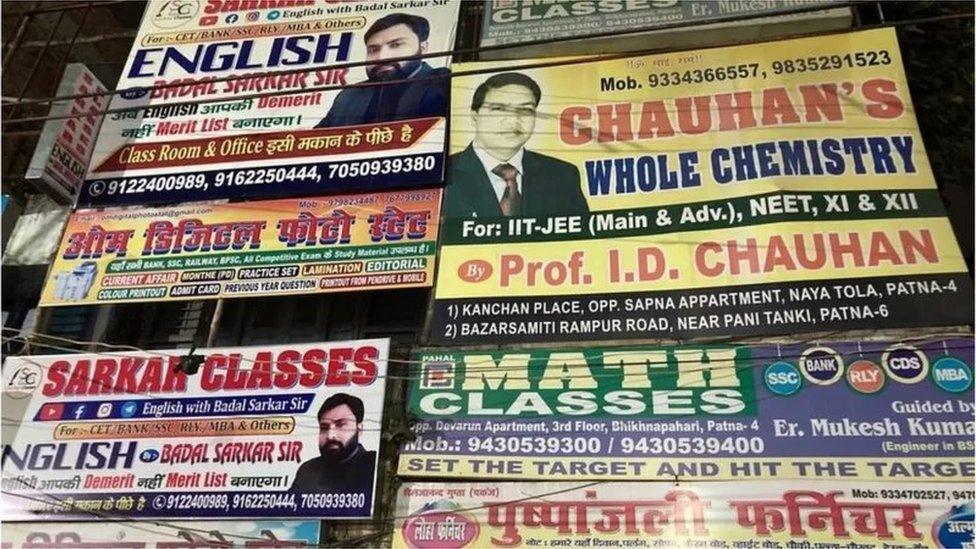

Patna's skyline is cluttered with coaching class adverts

Not that there are jobs elsewhere. India's unemployment rate crept up to nearly 8% in December, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), an independent think tank. It was more than 7% in 2020 and for most of 2021. Economists say this is way higher than anything seen in India, at least over the last three decades.

The number of active job seekers in the working age population has fallen: only 27% of people aged 15-24 are either working or looking for a job. The more educated the person is, the more likely it is they'll remain jobless and unwilling to take up low-paying and precarious informal jobs. The proportion of women, aged 15 and older, in the workforce is among the lowest in the world.

The youth - 18 to 29 years - have traditionally borne the brunt of joblessness in India. And as more of the young go to schools and colleges, the educated youth have the highest unemployment rate in India, according to Radhicka Kapoor, a labour economist. "This is not a new problem and has been brewing for a long time," she told me.

India is simply not producing enough jobs - and quality jobs - for its youth. Labour surveys have shown a quarter of the youth are sitting at home doing "unpaid family work", essentially lending a helping hand to family members and preparing for exams. Only a third had regular jobs, but 75% of them had no written contracts and 60% were not eligible for social security.

The scramble for government jobs - in the railways, for example - also showed that young Indians preferred those steady, protected jobs over the much vaunted gig economy work, says Dr Kapoor. "Gig economy work is precarious and volatile with no steady career path. That's not what an educated young person wants. Glamorising gig economy work as a solution is not an answer to the jobs crisis".

The protests spread to neighbouring Uttar Pradesh

In places like Bihar, the jobs crisis has been exacerbated by the growing crisis in the farms. Land holdings are small, farming is becoming unremunerative. Farming families are selling land and borrowing money to send their children to the cities to take up private coaching. Many of them are first-generation literates, aspiring for white-collar jobs in a jobs-scarce economy.

The abysmal standards of state-run schools and colleges do not inspire confidence. The skyline of Bihar's capital, Patna, is cluttered with adverts of private coaching schools that promise to help aspirants pass tests for government jobs. Now the teachers are telling their students there are no jobs in sight: six coaching school teachers have been named in police complaints for instigating the riots.

This week's largely leaderless and spontaneous riots also tell you how India's political parties are failing to grapple with the crisis of jobs. Bihar's agitating students say they took to the streets after nobody paid heed to their protests on social media.

Studies in Indian cities have shown that lack of jobs in households leads to high levels of domestic violence. Other studies, external show that "there are no grounds empirically for the commonly made claims that there is a strong, automatic causal connection from unemployment, underemployment, or low productivity employment to violence and war" .

But it would be wise to bear in mind that much of the civic unrest that sparked the Emergency - when then prime minister Indira Gandhi suspended civil liberties and jailed thousands of people - in 1975 began with unrest over lack of jobs and high prices.

A survey early in the Emergency showed some 24% of young Indians between 18-24 were out of work. Some of the biggest protests in the run-up to the darkest chapter in Indian democracy then took place in Bihar.

You might also like:

Modi's India: Is Modi failing the jobless?

Read more by Soutik Biswas