Marital rape: Delhi high court gives split verdict

- Published

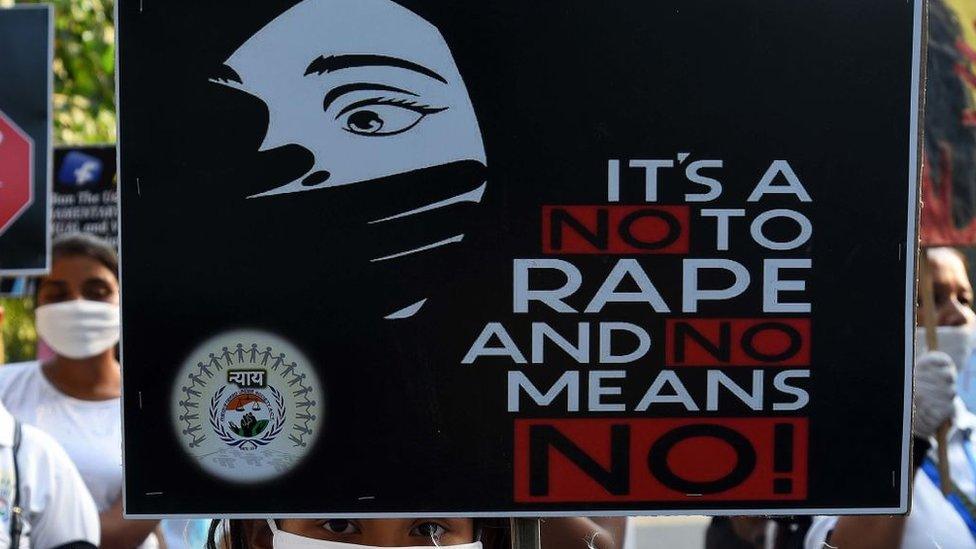

Many Indian women are still reluctant to complain about sexual violence

An Indian court failed to deliver a verdict in a case seeking to outlaw marital rape after two judges expressed opposing views.

One judge struck down an exception in a British-era law that says a man cannot be prosecuted for rape within marriage.

But the second judge refused to modify Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code which says sex "by a man with his own wife" who's not a minor is not rape.

The case is now expected to be appealed in the Supreme Court.

Wednesday's Delhi high court order comes as a setback for feminist advocates who have been campaigning for a change in the law, which has been in existence since 1860.

Over the years, more than 100 countries have outlawed marital rape - including Britain in 1991.

But the law remains on the statute books in India, with the idea for the exception rooted in the belief that consent for sex is "implied" in marriage and that a wife cannot retract it later.

Campaigners, however, say that forced sex is rape, regardless of who commits it.

But the Indian government and religious groups have opposed the petitions over the years, saying marriages are sacrosanct in India.

What did the judges say?

In his order on Wednesday, Justice Rajiv Shakdher said that an exemption to a man from the offence of rape for forcible sex with his wife is violative of article 14 and, therefore, unconstitutional. But Justice Hari Shankar disagreed with Justice Shakdher and said he believed an exception in the marital rape law did not violate the constitution and it was "reasonable".

In January, while hearing the case, the two-judge bench had asked how the dignity of a married woman could be differentiated from that of an unmarried woman.

"Whether she is married or not, she has a right to say 'no'. Have other countries [which criminalised marital rape] got it wrong?" asked the bench.

The justices said the exception under Section 375 had created a "firewall" and the court had to see if this violated other rights accorded under the constitution.

The law had been questioned by several judges in previous cases. In March, the Karnataka high court refused to dismiss rape charges filed by a woman against her husband.

"A brutal act of sexual assault on the wife, against her consent, albeit by the husband, cannot but be termed rape," the judge had said.

What did the petitioners say?

The petitioners had argued that the exception granted to husbands was unconstitutional because it violated several fundamental rights of a married woman such as the right to equality, the right to life with dignity and the right to self-expression.

They said it created a loophole in which instances of physical domestic abuse, including and up to murder, was criminal, but not rape - which in other circumstances was also a criminal act.

They also said that since instances of false reports were few compared with the scale of the problem, that should not stop the court from criminalising the act.

More than 100 countries have outlawed marital rape

Advocate Karuna Nundy, who appeared for the petitioners, argued that until marital rape was explicitly outlawed with consequences, the "bodily integrity of wives" would continue to be violated.

During the hearing, senior lawyer Rebecca John said the marital rape exception was based on archaic principles.

"There can be an expectation [regarding sex in a marriage] but expectation cannot lead to forcible sex with your wife," she said.

What did the government say?

In a 2017 affidavit in the court, the Indian government said that criminalising marital rape could have a "destabilising effect on the institution of marriage".

"What may appear to be marital rape to a wife may not appear so to others," the government said, adding that removing the exception may provide "an easy tool for harassing husbands".

The affidavit also asked the court to add states as parties for their opinion.

But in January this year, the government told the court it was holding consultations on the matter, leading to speculation that it could be rethinking its stance.

Religious groups, charities and men's rights activists have also opposed the petitions saying the law could be misused to harass men.

Related topics

- Published29 August 2021

- Published19 April 2019

- Published3 May 2022