Covid-19: Should India be bracing for a fourth wave?

- Published

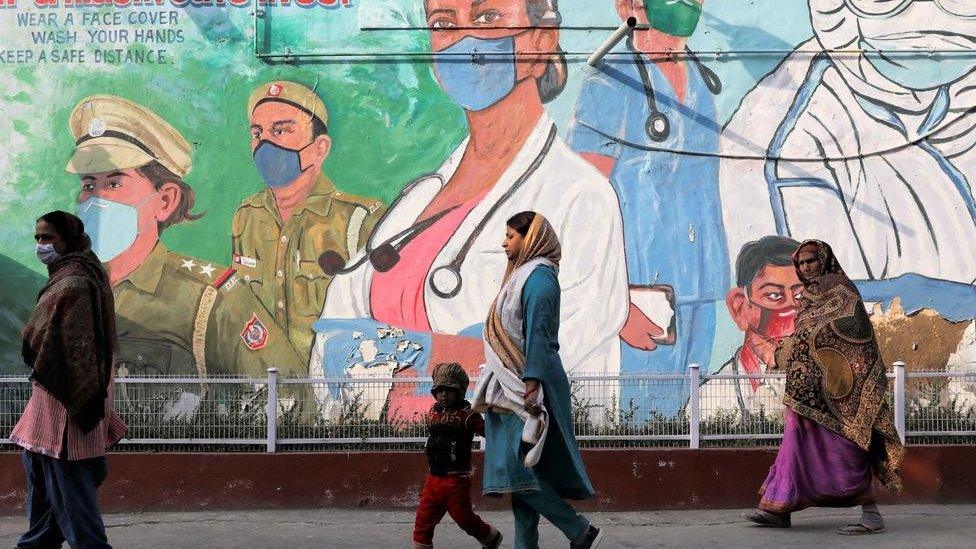

With more than 40 million confirmed cases, India has the world's second biggest caseload

There's a fresh surge in Covid cases around the world - infections are rising in the UK and parts of Europe. China and Hong Kong are seeing their largest spike in cases in more than two years.

With more than 40 million confirmed cases, India has the world's second biggest caseload, behind US. More than half a million deaths have been officially recorded - the third largest toll in the world.

Is there reason to believe the country should prepare for a fourth wave?

How is India doing now?

The good news is that daily new cases have fallen to their lowest in nearly two years.

The Omicron variant - which carries more than 50 genetic mutations and is now causing a fresh wave of infections in parts of the world - ripped through India in the winter. Cases have now receded.

India was hit by a brutal second wave of infections last year

On 21 March, India recorded 1,410 new cases, down from a surge peak of 347,000 cases on 21 January. Cases declined quickly, there were fewer severe cases than in previous waves and hospitals were not overwhelmed.

India has administered more than 1.8 billion doses of vaccine so far, fully vaccinating 80% of adults. Some 94% have received the first dose. So restrictions have been lifted, and much of life and business has returned to normalcy.

"India is breathing easy," says Dr K Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, a Delhi-based think tank.

Should India worry about a fresh wave?

A controversial modelling study by scientists at IIT, India's top technology school, has predicted a fourth wave beginning in June and peaking in August.

But many epidemiologists are deeply sceptical of the study and cautiously optimistic about the future.

One reason, they say, is that most Indians have acquired protective immunity to the virus by contracting the infection or by getting the vaccine. Also, a majority of Indians are vaccinated - and many have had breakthrough infections after being jabbed.

Indians play Holi, the festival of colours, earlier this month - life has largely returned to normal

"We are in a good place. We have a high level of vaccination and the government should be commended for that. We also have a high level of infection in the population which we acquired during several waves," says Dr Gagandeep Kang, one of India's top virologists.

Secondly, the uptick of cases in Europe and elsewhere is being caused by an easily spread sub-variant of Omicron called BA.2. In February, Indian scientists sampling sequences reported that BA.2 - a virus which is also better able to evade the vaccine - was already the dominant strain fuelling the country's Omicron surge.

In other words, India's BA.2-driven wave appears to be over. "The possibility of a large-scale nationwide wave of infections in India in the near future is very low," says Dr Chandrakant Lahariya, a physician epidemiologist.

But doesn't immunity wane over time?

It does. But some studies suggest three doses of a vaccine should help protect people from severe disease and death for a reasonably long time.

Booster shots help the body make more neutralising antibodies - a key part of our immune defences - to fight the virus. Since January, India has administered more than 20 million vaccine doses as boosters, curiously calling them "precaution doses".

Health and frontline workers and people above 60 years old with comorbidities are currently eligible to take the booster jab.

A policeman receives a booster dose of the vaccine in Mumbai

Yet India has still not announced a policy extending boosters to people below 60. This is not because it doesn't have enough doses.

Serum Institute of India, the world's largest vaccine maker, says it is sitting on a stock of 200 million doses of Covishield. This is the most used vaccine in India, accounting for more than 80% of administered doses.

Since the government has decided that the booster will be the same vaccine that was given to a person for their first and second doses, Covishield is mainly being given as a third dose.

Therein lies part of the problem. Virologist Shahid Jameel believes India is "ignoring the science behind booster doses".

mRNA vaccines - they use bits of genetic code to cause an immune response - such as Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna followed by a protein-based vaccine like Novavax are the best boosters available, he says.

mRnA vaccines are still not available in India. But Serum Institute is making a local version of Novavax called Covovax - it has already exported 40 million doses.

"Why is it not being approved as a booster in India? Should the best option not be available to Indians?" asks Dr Jameel.

India has begun giving the coronavirus vaccine to children aged between 12 and 14 years

A booster strategy needs to be driven by data which monitors precisely when vaccine protection begins to wane in different age groups. In the US, for example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has clear guidelines , externalon who can get a booster shot and when and which vaccine can be used.

India has approved nine Covid vaccines, five of which have been locally made. Only two have mainly been used.

"Rather than focusing on a programme that gives an additional dose of the same vaccine that people have got before, this is the time for India to research and figure out what is the right time to give the boosters and which vaccines would work as the best boosters," Dr Kang says.

A senior health ministry official told the BBC that the government was planning to expand the booster programme soon to include people under the age of 60.

Could a nasty new variant upend the return to normalcy?

Yes, say epidemiologists. But there are caveats.

"That variant must have characteristics that are very special. It needs to be able to infect and cause disease in those who have been previously vaccinated and infected," Dr Kang says.

"That's a high bar to set for a virus. But you can't rule it out. The more the virus continues to circulate and replicate, the more options it has to evolve in many different directions, one of which might be a virus which could be more infective and cause severe disease."

Dr Jeremy Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport, says that India - and indeed the world - needs to stay vigilant for new variants.

India has run a successful vaccination programme

With Omicron, he says, the world benefited from the South African scientists who sounded an alarm early.

"I am not convinced that we will be so lucky next time, and it's all but inevitable that we will see a new variant".

It is difficult, he adds, to predict when a variant as big as Delta or Omicron would emerge next, "but another three to nine months at the maximum seems like a reasonable guess".

So what about the near future?

In densely populated countries such as India, living with the virus is possible only when most people have some good protection against severe diseases through previous infection or immunisation - something Indians appear to already have.

"So we might expect to see sporadic outbreaks and local spikes in cases, not very large and concerning waves," says Dr Kamil.

The elderly and vulnerable - who can catch the infection many times despite vaccination and experience worse symptoms - have to be very careful as immunity wanes. India also has a younger demographic with a high burden of diabetes and cardio-respiratory diseases. They both need to get boosted.

Also, epidemiologists such as Dr Kang believe India needs to sequence more samples and sequence fast - "India is just not sequencing enough samples. It's a very big chink in our armour".

As Covid appears to transmit indoors more easily than outdoors, India's crowded and poorly ventilated workplaces need to adopt hybrid working, make sure that employees wear masks in office, and employers should pay for booster doses to employees when vaccines are sold privately, according to Dr Reddy.

"It should all be manageable. We should not freeze into immobility when spikes or waves happen. But we should take a few common-sensical precautions like wearing masks and avoiding unnecessary social activities," he adds.