Fabindia: Why India's popular clothing brand irks the right-wing

- Published

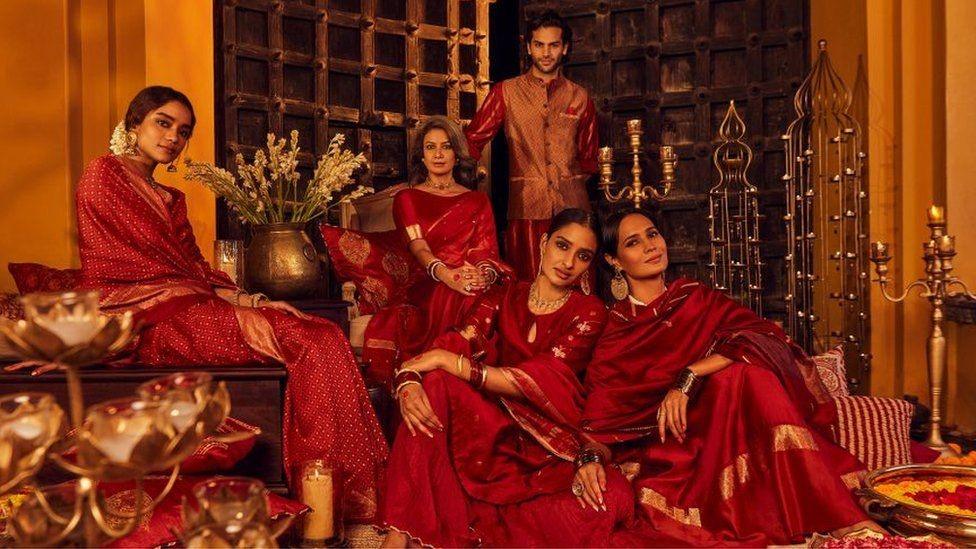

FabIndia's fashionably ethnic clothes makes it a big draw with India's middle-class

India's most well-known clothing retailer, Fabindia, known for its ethnic attires, has often found itself in the crosshairs of the country's right-wing. Why does a brand rooted in local traditions get a bad rap from the nationalists?

Last October, a Bollywood filmmaker fired off a missive against India's largest clothing brand.

Vivek Agnihotri is the maker of The Kashmir Files and is known to be a supporter of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). His ire was directed at Fabindia, India's biggest retailer for handloom and handcrafted products. The same month the retailer had withdrawn an advert about a new festive line after a backlash from right-wing Hindu groups.

In a five-tweet thread, Mr Agnihotri accused Fabindia of being the favourite of India's "uncultured" champagne-sipping liberals aligned to the main opposition Congress party. He also took a pot shot at the six-decade-old retailer's foreign roots: Fabindia was founded by John Bissell, an American businessman, in 1960, who arrived in India on a Ford Foundation grant.

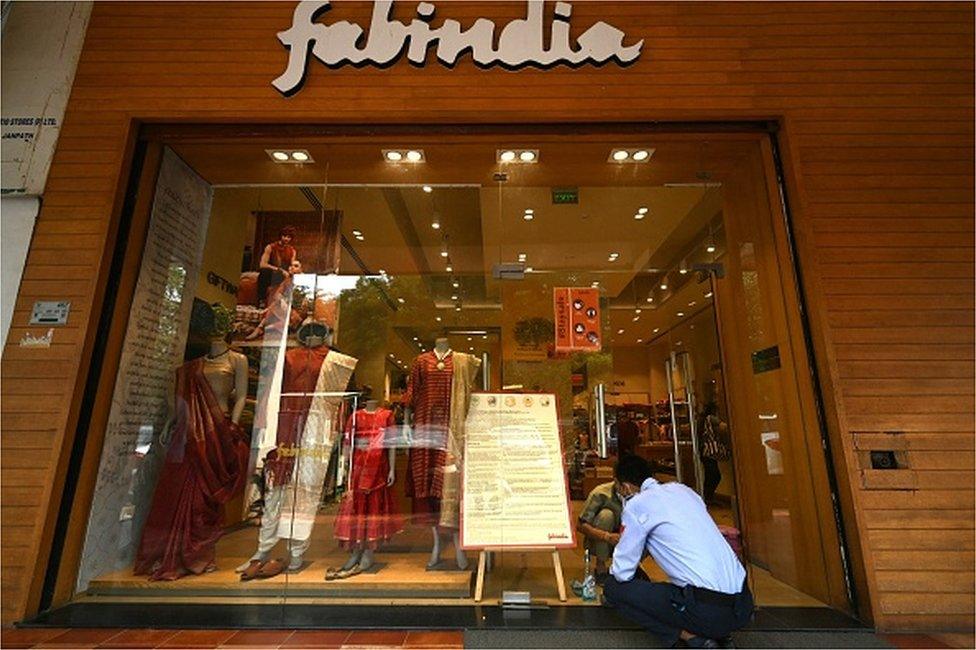

Mr Agnihotri's screed was not the first against the retailer, which runs more than 300 outlets in 123 Indian cities and 11 stores internationally.

In 2012, best-selling author Chetan Bhagat, tweeted that "wearing Fabindia", among other things, did not make you an intellectual.

India's liberals have been roasted on social media ever since Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu nationalist party swept to power in 2014. People wearing Fabindia's ethnic handwoven and handprinted clothes have provoked wide-ranging emotions - from gentle ribbing to outward scorn - in what is a manifestation of a divided country. Like elsewhere in the world, the right-wing in India is waging a war on liberalism - it believes the left-wingers lecture, mock and belittle them.

So Mr Agnihotri had pointedly tweeted that Fabindia's "target audience has always been pseudo people...who want to look Indian without anything to do with Indian culture".

This is a vexing argument. "Yes, when Fabindia began it was an elite brand," says Radhika Singh, author of The Fabric of Our Lives: The Story of Fabindia. It was launched as an export business in 1960, contracting villagers to make traditional rugs. Rejects were sold to well-to-do Indians from a warehouse in Delhi. The first store opened in Delhi in 1974.

By the end of the 1990s, Fabindia had grown into a household name and a thriving domestic retailer which in the words of Sunil Sethi, a journalist, had begun defining the "look of the Indian middle class".

FabIndia runs more than 300 outlets in 123 Indian cities

Its hand-woven and hand-printed clothes and designs were wedded in local crafts and tradition. The firm claims to support more than 55,000 artisans from across India.

In other words, the Fabindia look was created "in dialogue over decades together with designers, buyers and artisans", according to Jane Lynch, an anthropologist at Yale University who has researched the firm. "Fabindia clothes are made of cotton, easy to wear, light. They have a familiarity of tradition and a cool quotient," says Meeta Mastani, co-founder of Bindaas Collective, a social enterprise that sources directly from craftspeople.

In the public perception, the brand appears to be in some kind of a flux.

Today, it has expanded to also sell furniture, upholstery, rugs and organic food. Fabindia describes itself as "India's largest private platform for products that are made from traditional techniques, skills and hand-based processes". Indian publications now refer to it as a "lifestyle retail brand". The Economist magazine once called it a "purveyor of fancy clothes and crafts".

When she was doing her research on FabIndia, Jane Lynch found people would often "identify themselves as a Fabindia person or ask if I was one". Dr Lynch says this was a "cosmopolitan middle-class identification" rooted in concerns about the country's artisans and heritage.

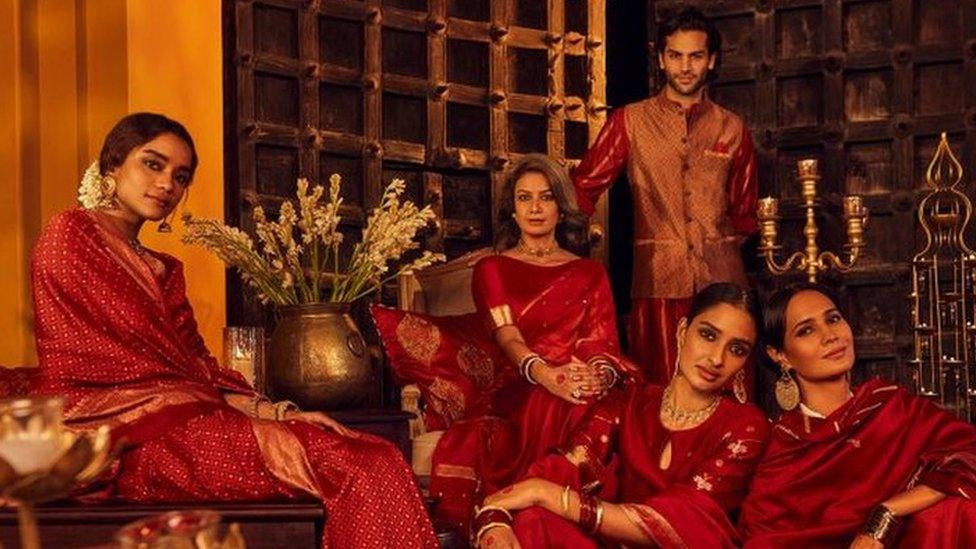

By 2000 FabIndia became a hugely popular retailer

To be sure, Fabindia's clothes have never really been identified with India's "protest fashion" - if anything that distinction belongs to khadi, the hand-spun fabric introduced during the freedom movement as a symbol that Indians could be self-reliant on cotton, free from the goods and clothes being sold to them by the British. In Mr Agnihotri's contested reading, the "genuine" people still wore khadi today, and "pseudos" wore Fabindia.

So how did Fabindia get associated with liberals in India? (The retailer declined to be interviewed for the piece.)

"Well, invoking the ire of the right-wing isn't tough at all. With Fabindia, the narrative is a little more complex given the elite tag. And the ownership issue, of course, plays a part. It is a brand created and driven by 'non-desis' [non-locals]. So does it really represents 'us'?," wonders Shobhaa De, one of India's most popular writers.

Ms De believes that Fabindia is a brand that caters to the "well-heeled jholawalas, who want to appear hip and cool in ethnic wear that's also pretty expensive". (Jholawala has been, for a long time, a disparaging reference to activists in India who carry cheap cloth-made sling bags.) "Fabindia is [about] reverse snobbery. Slumming it - but in style!" says Ms De.

To put it another way, says Santosh Desai, a columnist, Fabindia's clothes represent a "comfortable middle ground between the dowdy ideology of jholawallas and modern-day capitalism". That in turn gets decoded as a "kind of cocktail activism of people who are fundamentally disconnected with what they aspire to associate with," he says.

FabIndia says it supports more than 55,000 artisanal workers in India

Sanjay Srivastava, a professor of sociology at University College, London, says Fabindia is linked to a crafts movement which was patronised by the Congress party at the peak of its power and clothes worn by "certain kinds of academic, mainly social sciences and humanities, which have been critics of Mr Modi".

"So FabIndia has been about an older middle class which has a hybrid sense of Indian-ness and not so much about economic elites. Their products cater to the metropolitan cultural elite. The increasing prominence of non-metropolitan cities in India - larger numbers moving from there to the big metros for jobs and where a great deal of a recent BJP support base lies - might also make Fabindia an important symbolic target," says Prof Srivastava.

Yet to associate all Fabindia-wearing people as deracinated liberals opposed to Mr Modi's party and its ideology, may be well missing the point. Dr Lynch says the people who shop at its stores "do not represent a singular or coherent political and moral perspective". Fabindia, she says, is "in part so interesting because of how it brings together people across social locations".

Many say they are puzzled why Mr Modi's supporters would choose to lampoon a firm whose products are sourced from thousands of artisans in far-flung villages - the prime minister himself has made "Make in India" a cornerstone of his industrial programme. The retailer plans to gift more than 700,000 shares to artisans and farmers when it makes its stock market debut later this year.

"It's a mass brand. Its clothes have also become the non-conformist's uniform. It's become an easy symbol to bait liberals," says Mr Desai.

You may also be interested in:

India's fashion industry has been asked to help make khadi a little more trendy

Related topics

- Published19 October 2021

- Published6 December 2014

- Published6 April 2013