Why Urdu language draws ire of India’s right-wing

- Published

Urdu is a hugely popular and widespread language in India but some want to disown it

Who does Urdu belong to?

India's right-wing seems to think it's a foreign import, forced upon by so-called Islamic invaders.

The latest fracas happened in April when a reporter from a far-right news channel barged into a popular fast-food chain and heckled its employees for labelling a bag of snacks in what she thought was Urdu. The label turned out to be in Arabic, which many say underlines the broad-brush attempt to classify anything that has roots in Islamic culture as the same.

Last year, clothing retailer Fabindia was forced to withdraw an advert whose campaign title was in Urdu after protests from ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leaders.

In the past, politicians elected to state assemblies have been barred, external from taking oath in Urdu; artists have been stopped from painting Urdu graffiti, external; and cities and neighbourhoods have been renamed. Petitions have been filed seeking the removal of Urdu words, external from school textbooks.

Such attacks on Urdu, many believe, is part of a larger push to marginalise India's Muslim population.

"It clearly shows that there is a pattern of attack on symbols associated with Muslims," says Rizwan Ahmad, professor of sociolinguistics at Qatar University.

Others say it also fits a broader right-wing agenda of the political rewriting of India's past.

"The only way that the political project of shackling Indian languages by religion can proceed is by cutting off modern Indians from a huge amount of their history," historian Audrey Truschke says.

"That severing may serve the current government's interests, but it is a cruel denial of heritage for everyone else."

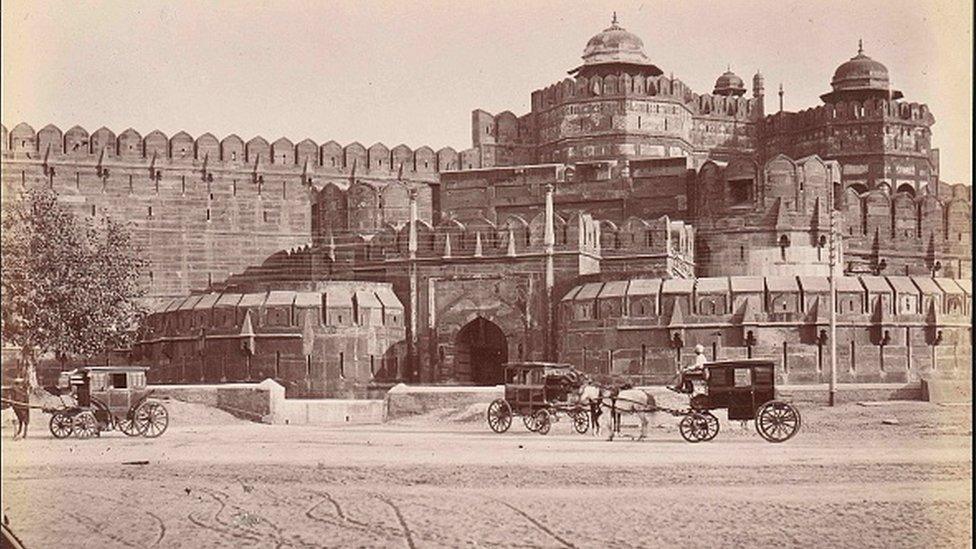

The birth of Urdu can be traced to the late 18th Century

The BBC tried to reach out to three BJP leaders in connection with this story but met with no response.

A supple and expressive language, Urdu has been the preferred choice for some of India's most famous poets and writers. Some of India's most acclaimed writing has come from Urdu writers like Saadat Hassan Manto and Ismat Chughtai.

Urdu's elegance and emphasis on smooth diction have inspired both fiery nationalist poetry and romantic ghazals (semi-classical songs). It has also been the beating heart of Bollywood songs.

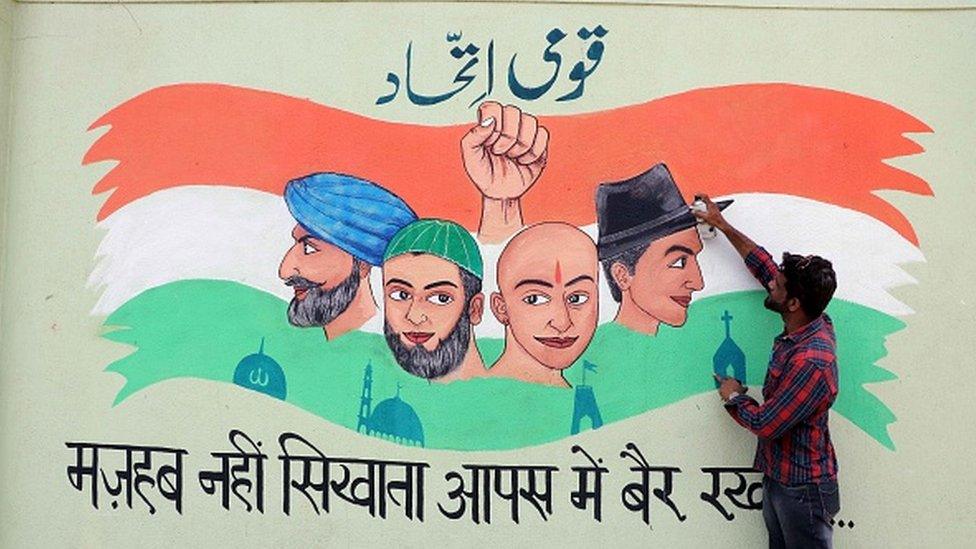

Opponents of the language say that Urdu belongs to Muslims whereas Hindus only speak Hindi. But history and lived experiences show quite the opposite.

What we know as Urdu today can be traced back to Turkish, Arabic, and Persian, all of which arrived in India through waves of trade and conquests.

"This common tongue was born out of the cultural hybridisation that happened in the Indian subcontinent," historian Alok Rai says.

"And it acquired different names over its evolution: Hindavi, Hindustani, Hindi, Urdu or Rekhta."

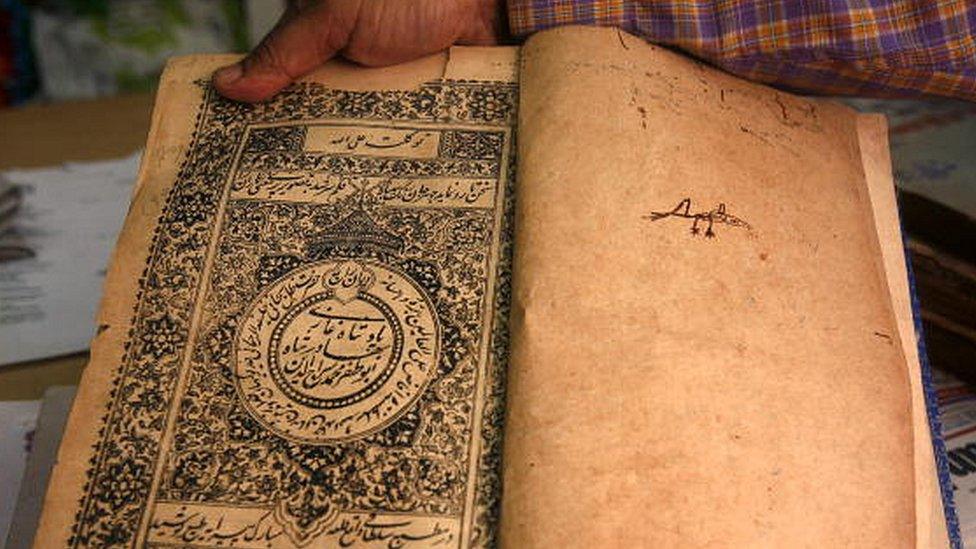

A rare Urdu book in a worn out state at a public library in Delhi

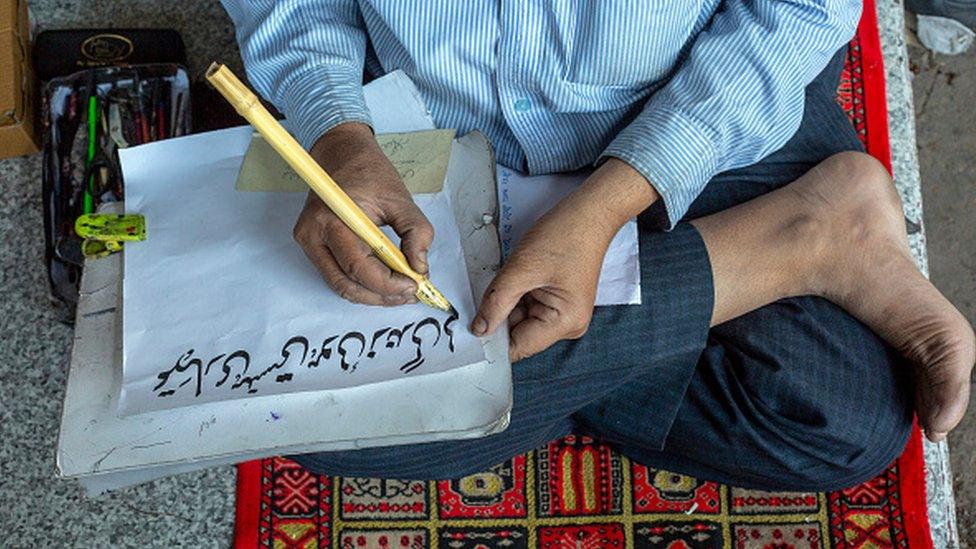

Dr Rai says that 'Urdu' - using quotes to differentiate it from its spoken forms - was the literary style invented in the last years of the Mughal dynasty in the late 18th Century by the aristocracy that clustered around the courts in Delhi.

This 'Urdu' was not seen as a Muslim language, as it is today, but had a class element - it was the tongue spoken by the elite of north India, which included Hindus as well.

'Hindi', on the other hand, was the literary style that developed in the late 19-20th Century in present-day Uttar Pradesh state, drawing from the same common base "but seeking to mark a difference".

While 'Urdu' borrowed words mostly from Persian - the elite lingua franca of medieval India - 'Hindi' took them from Sanskrit, the language of ancient Hindu texts.

"So both the languages rest on a shared grammatical base," Dr Rai explains, "but both Hindi and Urdu have also for political reasons developed myths of origin" .

What Dr Rai says is that speakers of both communities laid claim to what was a common language but ended up dividing it out of their anxiety of maintaining a separate identity.

"The whole situation would be slightly farcical if it didn't have such tragic consequences," he says.

The right-wing thinks Urdu belongs to Muslims whereas Hindus only speak Hindi - but that is far from the truth

The division was strengthened under the rule of the British, who began to identify Hindi with Hindus, and Urdu with Muslims. But the portrayal of Urdu as foreign is also not new in right-wing discourse.

Mr Ahmad says Hindu nationalists in the late 19th Century claimed legitimacy for Hindi as the official language of courts in north India. The British had changed the official language from Persian to Urdu in 1837.

The division reached its peak in the years leading to 1947 when India was partitioned into two separate states. "Urdu became one of the causes pursued by the Muslim League [which endorsed the idea of separate state for India's Muslims] and "an access to mobilisation for the demand of Pakistan", Dr Rai says.

Not surprisingly Urdu became an easy target - Uttar Pradesh banned it in schools and Dr Ahmad says that a lot of Hindus also abandoned the language at the time.

Dr Truschke says that with Urdu, the right-wing has tried to create a past which doesn't exist: "If Urdu is suddenly supposed to be an exclusively Muslim language, are we never to speak again of the many Hindus who have written in Urdu or that some of our earliest Hindi manuscripts are in Perso-Arabic script?"

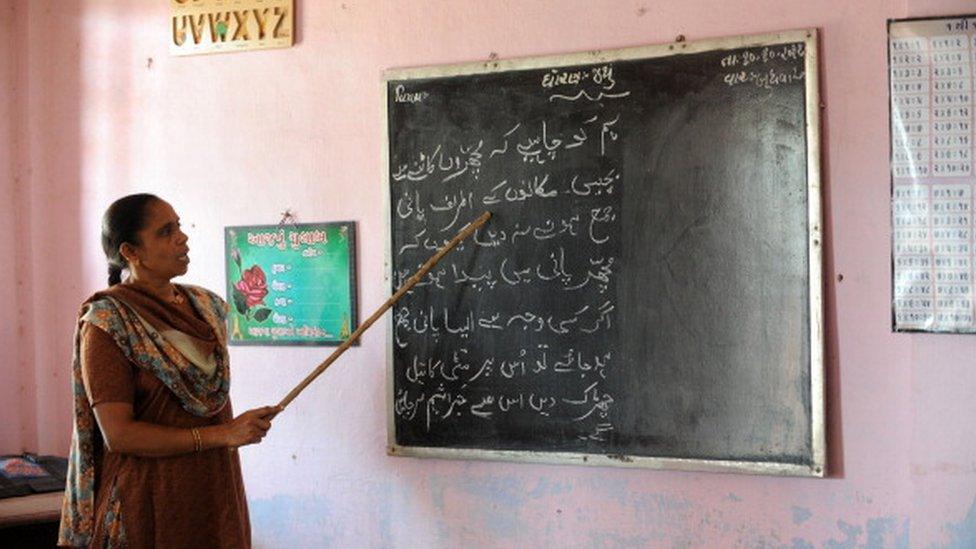

Schools in Uttar Pradesh state had banned Urdu in schools after Partition

Also, what about Urdu words which are liberally used in Hindi speech?

"The word jeb or pocket comes from Arabic via Persian. What is the Hindi equivalent? Probably none. And what about the timeless words like mohabbat (love) or dil (heart)?," Dr Ahmad says.

At the same time, languages are also markers of a faith, he adds.

"Urdu-speaking Muslims are more likely to use the word maghrib for sunset than Hindus. This is not different from how the language of upper caste Hindus shows difference from that of the lower caste in the same village - each language exists on a continuum."

Mr Rai says that attempts to remove Urdu from Hindi has "degraded" the latter.

"This Hindi is not the language of popular speech, it is sterile and devoid of emotional resonance."

- Published2 September 2021

- Published13 October 2020