India farm law: Seven months after repeal, farmers are ready for new protests

- Published

Farmers say they might renew their protests

Fear, anger and lots of uncertainty.

That's what Bachittar Kaur and other women from her village in the northern Indian state of Punjab said they felt when they first began protesting.

They were among thousands of farmers who demonstrated on the borders of the capital, Delhi, against the agricultural reforms passed by the government in 2020. The protesters hunkered down on the edges of the city for over a year and stayed there against all odds - braving scorching heat, a bitter winter and even a deadly second wave of Covid.

"I had told my friends and relatives that I would die protesting but won't let these farm laws be implemented," Ms Kaur says.

A retired school teacher, she says it wasn't easy to leave her comfortable home and live on the streets in a tractor trolley. "But we had no choice - these farm laws were death warrants for us."

For months, the government insisted that the laws were good for farmers and there was no question of taking them back - several rounds of talks between officials and farm leaders failed to end the deadlock. Several farmers died and many were arrested as the government clamped down on demonstrations.

But the tides turned on 19 November when Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a historic U-turn announced a repeal of the laws. A bill was officially passed in the parliament on 30 November.

The farmers didn't leave immediately though - they said they would continue to demonstrate until the government agreed to their other demands, including guaranteed prices for key crops.

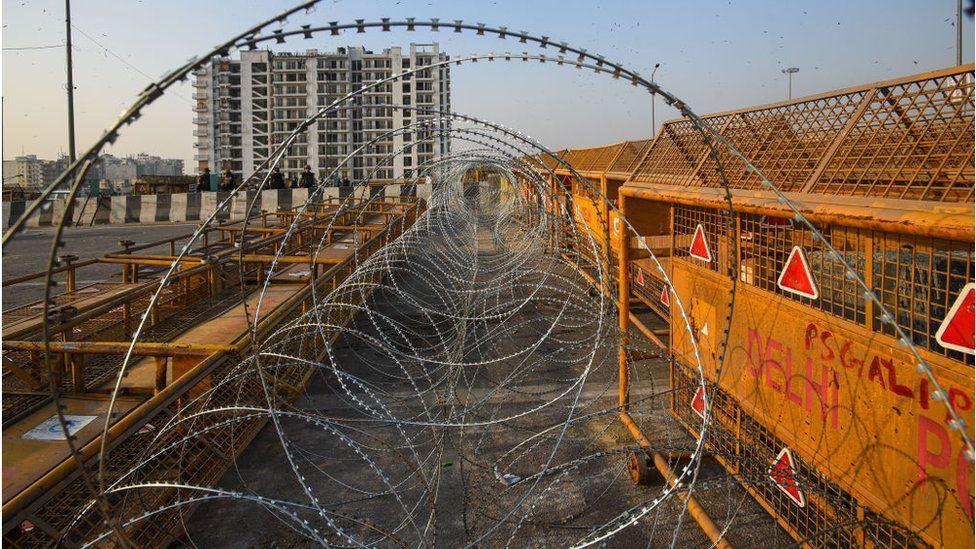

Tens of thousands of farmers had camped on Delhi's borders for over a year

Days later, the government accepted this too, bringing an end to the year-long protests.

Ms Kaur remembers it to be a "very special" moment of her life.

But seven months after farmers went back home, the government is yet to fulfil their demands.

Farm leaders have now called a meeting on 3 July to decide the next course of action. The meeting is to be held in Ghaziabad city near Delhi and will be attended by prominent farm leaders, including Rakesh Tikait, who spearheaded the protests.

Farmers ended their protests after the government repealed the agriculture laws

And farmers are not ruling out the possibility of another agitation.

"We are just waiting for leaders to decide the time and place," Ms Kaur says. "We are prepared for what comes next."

The protests first began in November 2020, when hundreds of thousands of farmers marched towards Delhi after the government introduced three laws that loosened rules around sale, pricing and storage of farm produce - rules which have protected them from the free market for decades.

One of the biggest concerns of the protesters was that the new laws allowed farmers to sell their produce at a market price directly to private players - agricultural businesses, supermarket chains and online grocers. Most Indian farmers currently sell their produce at government-controlled wholesale markets or mandis at assured floor prices (also known as minimum support price or MSP).

The government argued that the laws would make farming more profitable but the farmers disagreed. They said the laws would leave them at the mercy of big corporations who would dictate prices.

When the government finally announced that it would rollback the laws, it promised to form a committee, including representatives from the federal and state governments, agriculture scientists and farmer groups to look into the matter of MSP.

Union Agriculture Minister Narendra Singh Tomar told the Lok Sabha two months ago that the government was in the process of setting up the panel.

But sources in the federal government told the BBC that this has not happened. They said the government had asked farm leaders to name their members for the panel, but farmers refused to do so, saying the government's "intent was not clear".

"The government has announced MSP on some crops, but it also remains to be seen whether it will be available in all the states. They also need to first tell us the agenda of the meeting and how they plan to formulate the policy around MSP," says Joginder Singh Ugrahan, president of Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU) Ugrahan, one of the biggest farmer unions in Punjab.

Prominent farm leaders like Rakesh Tikait (Centre) will meet on 3 July to decide their next step

Besides MSP, farm leaders had put forth several other demands, which included compensation to the kin of farmers who died during the agitation, dropping criminal proceedings against them for burning paddy straw, and withdrawal of criminal cases registered against them for protesting.

Mr Ugrahan says that in November, after the laws were scrapped, the agriculture secretary had written to Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) - the umbrella body of farmer unions that led the protests - assuring them that they would comply with these demands.

While some of the conditions have been met - several states have given monetary compensation to farmers - criminal cases against protesters continue to be a contentious issue, he says.

Most cases were registered in the state of Haryana as the protest sites mainly fell in its jurisdiction.

The state's Home Minister Anil Vij told the BBC that the government had withdrawn most of the cases. "A total of 272 cases were registered during the agitation, out of which 82 have been withdrawn," he said

But the farmers are not convinced.

"This is just one state. We are still awaiting details [from the federal government] on the number of cases registered by different states and how many of those have been withdrawn," Mr Ugrahan says.

The government had clamped down on the protests, arresting several farmers

But even as farmers gear up for what could be potentially another protest, they worry if their movement has lost some steam in the meantime.

There has been disaffection within farm groups ever since some of its leaders contested the state elections in Punjab but failed to win a single seat. Following the results in February, the SKM expelled 22 of the 32 farm unions whose members had fought the election.

"This has definitely dealt a serious blow to the farmers' unity," Mr Ugrahan says.

But he says he hasn't lost hope: "One phone call, and I am sure all of us will come together," he says.

"It's a half-won battle, and the fight is very much on."

Related topics

- Published19 November 2021

- Published2 December 2020