Childhood obesity: Why are Indian children getting fatter?

- Published

After weeks of treatment and a gastric bypass surgery in 2018, 14-year-old Mihir Jain's weight came down to 165kg from 237kg

India has long topped the list of countries with the highest number of malnourished children in the world. It's now increasingly also reporting alarming levels of childhood obesity which, experts say, could take on the form of an epidemic if not tackled urgently.

When 14-year-old Mihir Jain first rolled into Delhi's Max Hospital in 2017 in his wheelchair to consult Dr Pradeep Chowbey, the bariatric surgeon said he "couldn't believe my eyes".

"Mihir was super-super obese, he couldn't stand properly and he wasn't able to open his eyes as his face was fluffy. He weighed 237kg (523lbs) and his body mass index (BMI) was 92." According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a BMI of 25 or above is considered overweight.

After weeks of treatment and a gastric bypass surgery in the summer of 2018, Mihir's weight came down to 165kg.

At the time, Mihir was described as the "world's heaviest teen" - the label could be an exaggeration, but India is home to an estimated 18 million overweight and obese children and their number is rising daily.

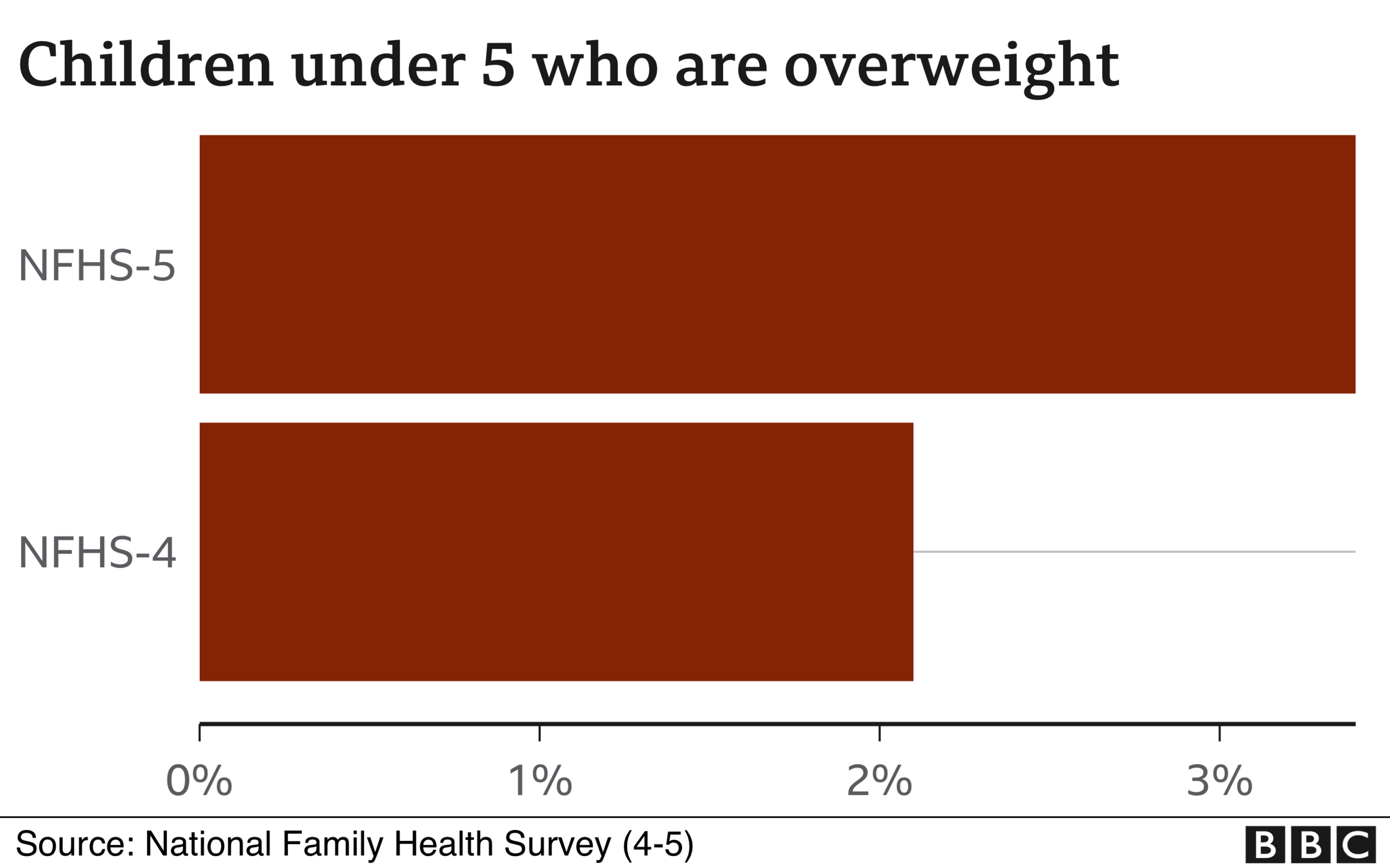

The latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5, conducted in 2019-21), the most comprehensive household survey of health and social indicators by the government, found that 3.4% of children under five are now overweight compared with 2.1% in 2015-16.

On the face of it, the numbers seem small, but Dr Arjan de Wagt, chief of nutrition at Unicef in India, says that "even a very small percentage can mean very large numbers" because of the size of the Indian population.

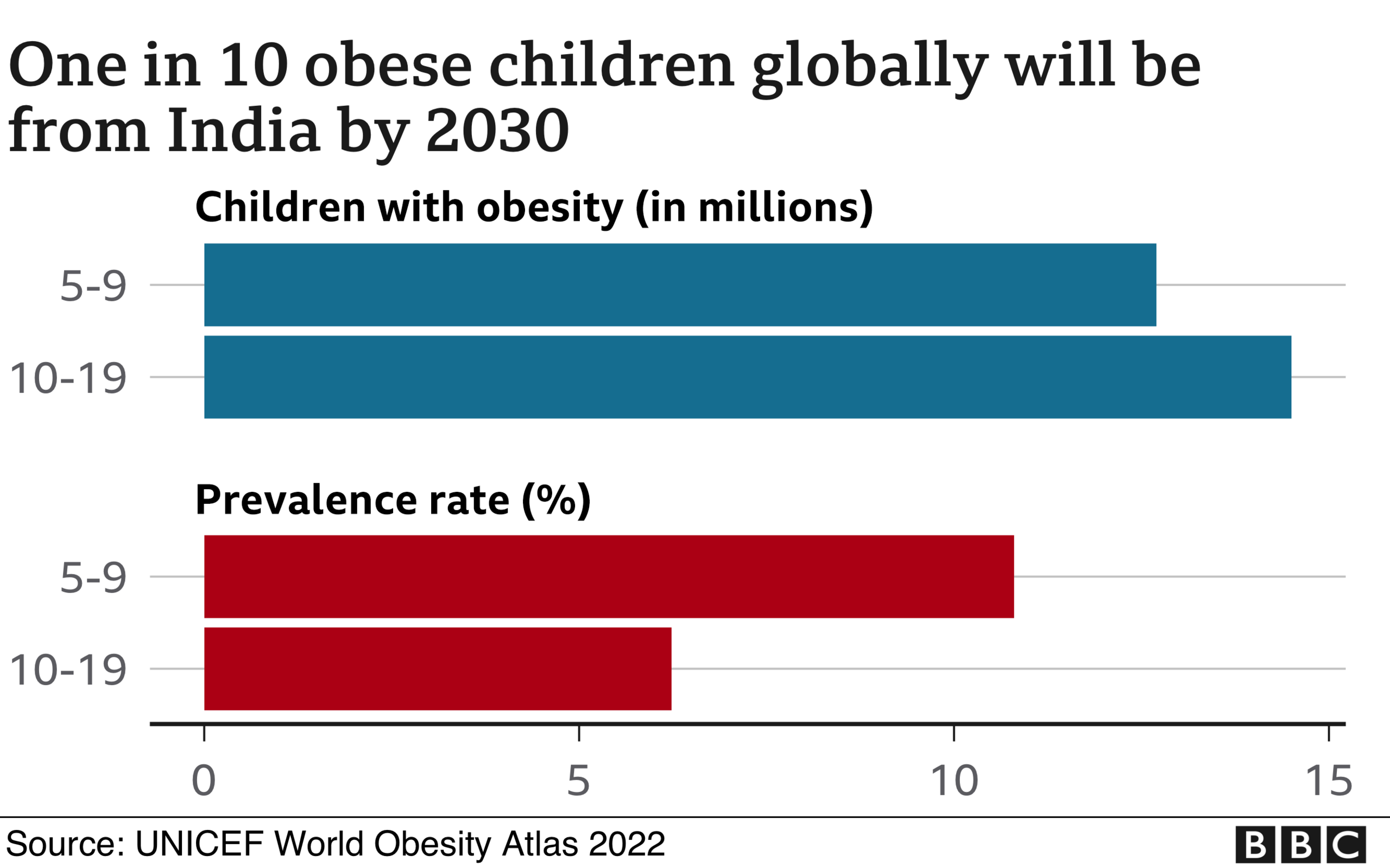

According to Unicef's World Obesity Atlas for 2022, India is predicted to have more than 27 million obese children, representing one in 10 children globally, by 2030. It ranks 99th on the list of 183 countries in terms of preparedness to deal with obesity and the economic impact of overweight and obesity is expected to rise from $23bn in 2109 to a whopping $479bn by 2060.

"We are staring at a massive problem of childhood obesity in India," says Dr de Wagt. "And because the behaviour that starts obesity generally starts in childhood, obese children grow up to be obese adults."

And that is a major worry for health experts. According to WHO, too much body fat increases the risk of non-communicable diseases, including 13 types of cancer, type-2 diabetes, heart problems and lung conditions, leading to premature deaths. Last year, obesity accounted for 2.8 million deaths globally, external.

India has already broken into the top five countries in terms of adult obesity in the past few years. One estimate in 2016 put 135 million Indians as overweight or obese and their numbers are growing.

Dr de Wagt says that in India - where 36% children under five years are still stunted - the gains we've been making in combating undernutrition are offset by over-nutrition.

"People are under-nutritioned and over-nutritioned at the same time. Overweight and obesity are results of overnutrition, but that doesn't mean that one's getting all the nutrition they need."

The biggest problem, he says, "is the nutritional illiteracy".

"If children are given balanced meals that include carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, fruits and vegetables, then it would prevent both undernutrition and overnutrition. But people don't know what is good food, they eat to fill their bellies. they're eating more carbs, more convenience food."

Dr de Wagt says data shows that although childhood obesity is a problem among all social classes, it is more common in urban richer families where children are being fed a diet of food and drinks high in fat, sugar and salt.

A 2019 survey by Max Healthcare in Delhi and its suburbs revealed that at least 40% children (5-9 year olds), teens (10-14 year olds) and adolescents (15-17 year olds) were overweight or obese.

"Youngsters sleep late and often resort to midnight binging, mostly on unhealthy snacks," says Dr Chowbey. "They do not burn any calories after eating late at night as they sleep after that and during the day, they are lethargic which means they burn few calories. Moreover, children are spending a lot more time on computers and phones instead of running around and playing."

"Obesity," he also warns, "impacts not just medical, but each and every aspect of life, including psychological and social. Obese children often face prejudice and social isolation."

Dr Ravindran Kumeran, a surgeon in the southern city of Chennai (Madras) and founder of the Obesity Foundation of India, says unless we intervene with children now, we will not be able to address the problem of obesity in the country.

"If you watch TV now for half an hour, you will see many advertisements about junk food and those glorifying soft drinks. This constant false messaging about benefits of unhealthy junk food must stop, and it can only be done by the government."

Also, he says, we need to get more children into the outdoors.

"As a country we don't invest in physical fitness. Our cities have no footpaths, there are no safe cycle tracks, and there are few playgrounds where children can play."

That's what Sportz Village, a youth sports organisation, is trying to change, its co-founder and CEO Saumil Majumdar told the BBC.

"In our country, schools are mostly the only places that offer a safe place for children to play, so schools must play their part in combating obesity," he says.

Their survey of more than 254,000 children showed that one in two children did not have healthy BMI; a large number of children lacked flexibility, had poor abdominal or core strength and fared poorly on upper and lower body strengths

It's not a problem of policy. All schools have physical education classes, but generally only children who are good get any attention. So it's not fun for children who don't enjoy playing," Mr Majumdar says.

"We believe that in schools just as children have to learn the basic level of any subject, in the same manner they must be taught the basic levels of fitness."

Over the years, he says, the schools they've worked with have shown improvements.

"In some cases we have seen fitness levels on some parameters improved from 5% to 17% and we've also managed to get more girls to play. I think play can solve all the world's problems," he adds.

Graphics by the BBC's Tazeen Pathan

Read more on India's family survey from the BBC: