Haryana: India's 'most wanted' who acted in 28 films and hid for 30 years

- Published

Om Prakash is in custody and has not commented on the accusations against him

Om Prakash - also known as Pasha - figured on the list of "most wanted criminals" of police in the northern Indian state of Haryana.

For 30 years, the former Indian army employee - wanted in connection with an alleged robbery and murder - hid in plain sight in the neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh. There, he acquired a brand-new life with official documents, married a local woman and raised three children with her.

But earlier this week, his luck finally ran out when police arrested the frail 65-year-old from his home in a slum in Ghaziabad city.

Until his arrest, police say, Om Prakash wore several hats - driving a truck, touring nearby villages as part of a group to sing devotional songs on religious occasions, even acting in 28 low-budget local films.

Om Prakash is in custody and has not commented on the accusations against him, but Sub-Inspector Vivek Kumar of Haryana's Special Task Force (STF), who was part of the team that arrested him, told the BBC that he blames an alleged accomplice for the 1992 murder.

Two days after Om Prakash's arrest made headlines, I went in search of his family to hear their side of the story - and what they would say in his defence.

Om Prakash acted in 28 films and even played a policeman in one

In the sprawling Harbans Nagar slum where narrow labyrinthine bylanes are unmarked and house numbers are not sequential, it took me three-and-a-half hours to track them down.

I met Rajkumari, his wife of 25 years, and two of his three children - a 21-year-old son and 14-year-old daughter.

From under the bedroom mattress, Rajkumari pulls out a Hindi newspaper with details of the accusations against her husband and says they are still in shock, that they had no idea about his "alleged criminal past" and that they are trying to wrap their heads around the revelations.

But if I had gone looking for the family to defend Om Prakash, it was a futile exercise - they do not have anything charitable to say about him.

They also accuse him of betrayal. "I married him in 1997, not knowing that he was already married and had a family in Haryana," Rajkumari alleges.

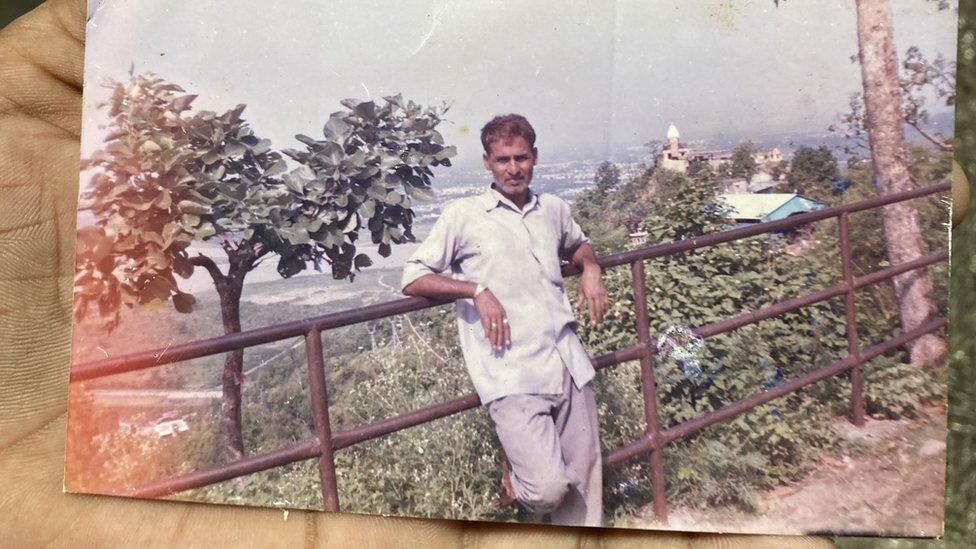

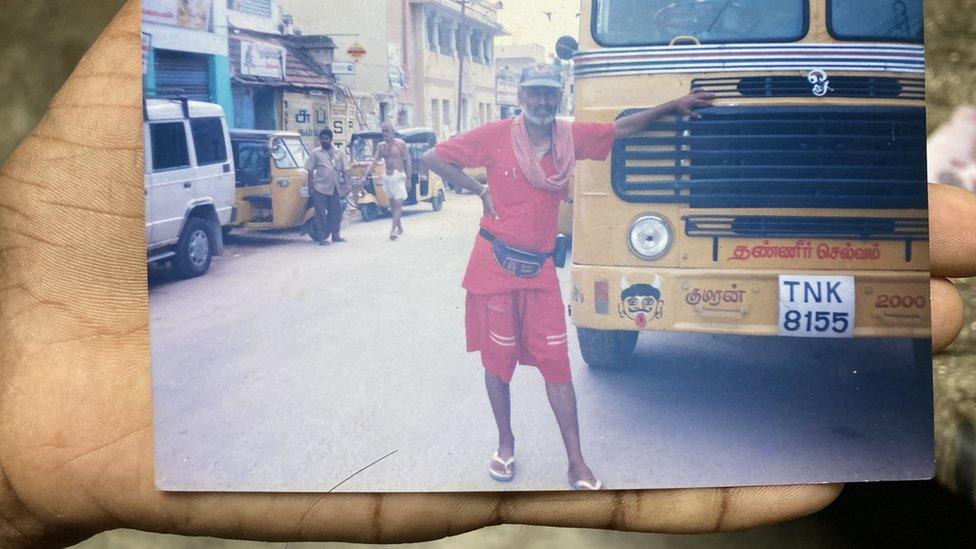

Om Prakash's son holds up a photo of his father from the family album

Who is Om Prakash - and what is he accused of?

A resident of Naraina village in Haryana's Panipat district, "Om Prakash worked as a truck driver for 12 years in the Signal Corps of the Indian army, before being dismissed in 1988 for being absent from duty for four years", Mr Kumar says.

Mr Kumar says Om Prakash had several brushes with the law even before the alleged murder - he allegedly stole a car in 1986 and, four years later, a motorbike, a sewing machine and a scooter. The crimes took place in different districts and in some of them, police say, he was arrested and later freed on bail.

In January 1992, Mr Kumar says that Om Prakash and another man tried to rob a man travelling on a bike.

"When the man resisted, they stabbed him. When they saw a group of villagers running towards them, they abandoned their scooter and ran away," he alleges.

The second man, Mr Kumar said, was caught and spent "seven-eight years in jail" before he was released on bail.

But Om Prakash vanished and soon the trail went cold. Police declared him a "proclaimed offender", and his file lay gathering dust.

Since his arrest, police say he's told them that he spent the first year after the alleged murder taking shelter in temples in the southern states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

A year later, he returned to northern India, but instead of going home, he established himself 180km (112 miles) away in Ghaziabad, where he found work driving trucks.

Rajkumari, who married him in 1997, says locally he's known as Bajrang Bali or Bajrangi, after a shop he ran in the 1990s, selling and lending video cassette recorders (VCRs) of films. He's also known as "Fauji Tau" - soldier uncle - a reference to his army years.

From 2007, he has also been doing small roles in local Hindi-language films, playing a village head, a villain, even a police constable, mouthing dialogues and jiving to songs. One of the movies - Takrav - has been watched 7.6 million times on YouTube. Clips from the film have notched up several more million views.

"He acquired a brand-new set of official documents such as a voter card and an Aadhaar card," Mr Kumar says.

But Om Prakash, police say, made one fatal error - all of his new documents contained his and his father's real names, which led to his undoing.

Rajkumari's story

Police agree that Om Prakash's new family or his neighbours had no idea about his alleged "criminal past".

Rajkumari says after their marriage, she did realise that Om Prakash was hiding something.

He took her to the Naraina village where he introduced her to his brother and his family, telling her that they were his friends.

A few years later, she says, she "found out about his earlier marriage when one day his first wife turned up and created a ruckus outside our home".

"That's when I, and all our neighbours, found out that he had another life - a wife and a son he had kept hidden away. We felt betrayed."

Their marriage, she says, was marked by his long absences, which she put down to his work as a long-distance truck driver - but now she insists that it was because he was visiting the other family.

Their relationship deteriorated, the couple fought regularly and in 2007, he disappeared again.

"I was so fed up that I cut him off, I went to a local government office and gave an undertaking in writing that I have nothing to do with him anymore. But he returned seven years later and has been visiting off and on," she says.

"He calls us names, but whenever he comes, we give him some food out of pity because he's our father and an old man," adds his 14-year-old daughter.

Rajkumari says that once previously, Haryana police took him away for a suspected case of theft.

"He spent six-seven months in jail then, but he returned and told us that he had been cleared of all charges," she says.

Despite the arrest, he had remained on the list of absconders in the murder case because police records are mostly not digitised and it's not common for police in different districts to talk to each other or share intel.

Om Prakash with the police after his arrest

How was he traced?

In 2020 - a year after Haryana formed the Special Task Force to mainly look at cases of organised crimes, narcotic seizures, terrorism and those that would involve crossing state boundaries - Om Prakash's file was reopened.

The force put him on their list of "most wanted" and announced a reward of 25,000 rupees ($315; £261) for information leading to his capture.

In the past too, there have been cases where criminals who have been on the run for a very long time, sometimes decades, have been arrested. But senior Indian Express journalist Amil Bhatnagar, who spent years in Ghaziabad tracking crime stories, says "police generally reopen cold cases only when they involve terrorism or serial murders or if they've received a tipoff". It's not entirely clear why the force decided to reinvestigate this case.

But two months back, police visited Naraina village and "spoke to people who were in their 50s and 60s, who would have some memory of Om Prakash".

That's where they got their first clues - that Om Prakash had visited the village about two decades back and that he could be living somewhere in Uttar Pradesh.

On their second trip, they found a phone number registered in Om Prakash's name and were finally able to trace his new address.

"The police staked the area for a week and identified his home. They say they also struggled with identification since they only had a 30-year-old picture and now he looks very different.

"We wanted to make sure we got the right man," Mr Kumar said.

"The operation was carried out with utmost secrecy because we were worried that one false move and he'd run away for another 30 years," he added.

What happens next?

The arrest of a man on the run for such a long time is being seen as a triumph for the Special Task Force, but Mr Bhatnagar says the real hard work for the police begins now.

"They have to prove in the court that they have got the right man. And the courts will have to examine in great depth whether he is the right man and whether he committed the crime he stands accused of."

Considering the crime took place decades ago, Mr Bhatnagar says, the quality of the evidence would also be in focus.

"The wear and tear of evidence is a very tangible aspect of crime cases. It'll be an uphill task for the police and prosecution to build a water-tight case."

Before I leave his home, I ask Rajkumari if she's tried to meet him since his arrest.

"The police say we have to submit our identity cards if we want to meet him, but I don't want to do that. What good could come out of that?"

Read more from the BBC's Geeta Pandey