Rohingya and CAA: What is India's refugee policy?

- Published

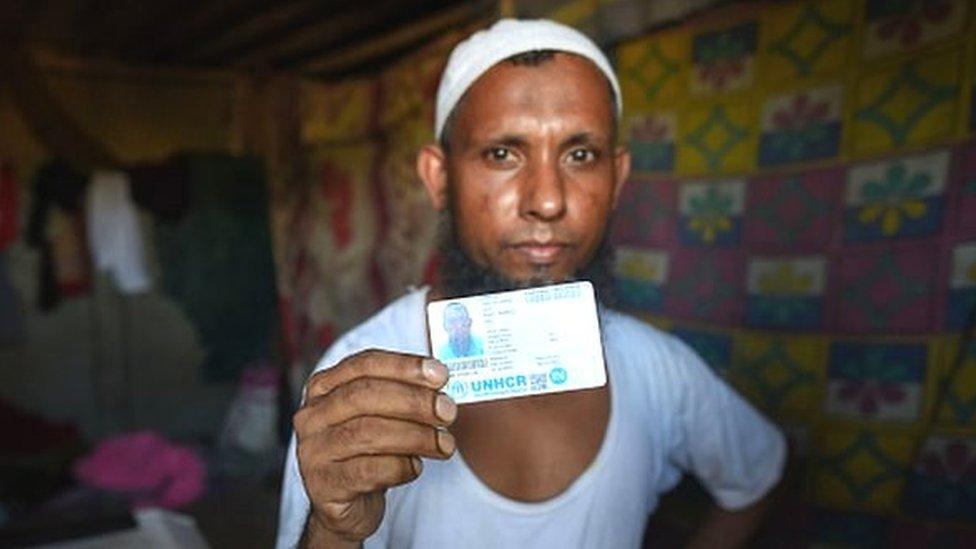

Rights groups have criticised India for its attempts to deport Rohingya refugees instead of offering them asylum

India's refugee policy is back in the spotlight after the government contradicted a minister's announcement that there are plans to provide housing and security to the Rohingya community in the capital.

Hours after Housing and Urban Affairs Minister Hardeep Singh Puri's tweet on Wednesday, the government said the refugees would be held in detention centres until they were deported.

The Rohingya Muslims are seen by many of Myanmar's Buddhist majority as illegal migrants from Bangladesh. Fleeing persecution at home, they began arriving in India during the 1970s and are now scattered all over the country, with many living in squalid camps.

In August 2017, a deadly crackdown by Myanmar's army sent hundreds of thousands of them fleeing across the border.

According to Human Rights Watch, an estimated 40,000 Rohingyas are in India - at least 20,000 of them are registered with the UN Human Rights Commission.

Rights groups have criticised India for its attempts to deport the refugees instead of offering them asylum.

Mr Puri's proposal to provide housing for the Rohingya was "perfectly correct", senior lawyer Colin Gonsalves told the BBC.

"The Rohingya cannot be put into detention camps as they have not committed any crime," he said. "They come here because they are forced to flee persecution."

How does India deal with refugees? What impact does it have?

India does not have a national policy or a law to deal with refugees. In his now-deleted tweet, Mr Puri wrote, "India respects and follows UN Refugee Convention 1951 and provides refuge to all, regardless of their race, religion or creed."

The country is, however, not a signatory to international laws such as the 1951 UN Convention and the 1967 Protocol, which secure the rights of refugees to seek asylum and protect them from being sent back to life-threatening places.

Experts say this leads to an "ad-hoc and arbitrary" manner of dealing with refugees irrespective of the party in power.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), refugees and asylum-seekers primarily live in urban India - 46% are women and girls, and 36% are children.

Refugees not recognised by the Indian government find it difficult to access housing and healthcare

An absence of documents can mean that refugees coming to India "have no access to basic facilities like healthcare, education and employment", says Suhas Chakma, director of think-tank Rights and Risks Analysis Group.

Refugees recognised by the Indian government can get access to education, healthcare, jobs and housing in camps.

But those registered with UNHRC get little protection in their daily lives and often do not get residential permits from the government, human rights lawyer Nandita Haksar said earlier this year, external.

What does law say about dealing with refugees?

Mr Chakma says India doesn't have a procedure that allows refugees to seek asylum and those entering the country without a visa are treated as illegal immigrants under the Foreigners Act or the Indian Passport Act.

The only protection they have is the right to life under Article 21 and protection against arbitrary abuse of power under Article 14 of the constitution.

In 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) which offers amnesty and expedites the path to Indian citizenship for non-Muslim "illegal immigrants" from the neighbouring countries, such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan.

But the law was widely criticised and triggered protests across the country. Political parties, civil society and Muslim groups said the law went against secular values enshrined in the constitution.

How are refugees treated in India?

The country's ad-hoc policy means all refugees do not get the same treatment.

"[Such] decisions are taken based on geopolitical and political considerations of the state and national governments," Mr Chakma says.

India supported Bangladesh's 1971 war of independence from Pakistan and took in tens of thousands of refugees from there.

The Tamil Nadu government provided Sri Lankan refugees with an allowance

Journalist Nirupama Subramanian pointed out, external that in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, Sri Lankan Tamil refugees were provided an allowance by the state government and allowed to seek jobs. After the end of the civil war in 2009, Tamil refugees could consult an agency like the UNHCR and decide whether they wanted to return.

India has for years supported the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees who followed him into exile and sought asylum in the country after a failed anti-China uprising in 1959. In 2018, after PM Modi's summit with Chinese President XI Jinping in Wuhan, India's foreign ministry discouraged government officials from attending events where the Dalai Lama or Tibetan officials were present.

But the relationship between the two countries worsened after a 2021 face-off along their disputed border in the Himalayan region.

In January, when China expressed concern over Indian lawmakers attending an event hosted by the Tibetan Parliament-in-exile, Delhi called their comment "inappropriate", external.

In the case of the Rohingya refugees, the country's decision to deport some men in 2017 sparked an international outcry.

Rajnath Singh, then federal home minister, insisted they were not refugees or asylum-seekers but "illegal immigrants.

Analyst Subir Bhaumik had told the BBC then that the community had become "a favourite whipping boy for the Hindu right-wing to energise their base".

The UN special rapporteur on racism, Tendayi Achiume, said later that India risked breaching its international legal obligations by returning the men to possible harm and that it was "a flagrant denial of the refugees' right to protection".

What does India need to do to have a fair policy?

"Successive governments have often said it's an issue of national security," Mr Chakma says.

In some cases, the Supreme Court stepped in to stop deportations if it found that they did not pose any threat or if sending them back could put their lives at risk.

Mr Chakma says India needs a legal framework so that refugees who enter the country are able to register themselves and access protections against arbitrary detentions.

But Mr Gonsalves, who is also founder of the Human Rights Law Networks, says the legal basis already exists - the constitution protects the rights of refugees.

Pushing Rohingya back across the border to Myanmar where their lives will be in danger will be in breach of the right to life under the constitution, he adds.

"The reason a lot of Rohingya refugees are not being deported at the moment is because there are a series of cases in the Supreme Court where the court has told the government not to take any precipitous steps," he told the BBC.

In 1996, the top court had ruled that the principle of non-return of a refugee is part of the right to life under Article 21 of the constitution.

This covers everyone within the territory of India - "citizens and non-citizens alike", Mr Gonsalves explained.

The government simply needs to implement it, he said.

You may also be interested in:

Rohingya crisis: Growing up in the world's largest refugee camp

Related topics

- Published10 April 2021

- Published23 January 2020

- Published4 October 2018