Is India seeing a decline in violence?

- Published

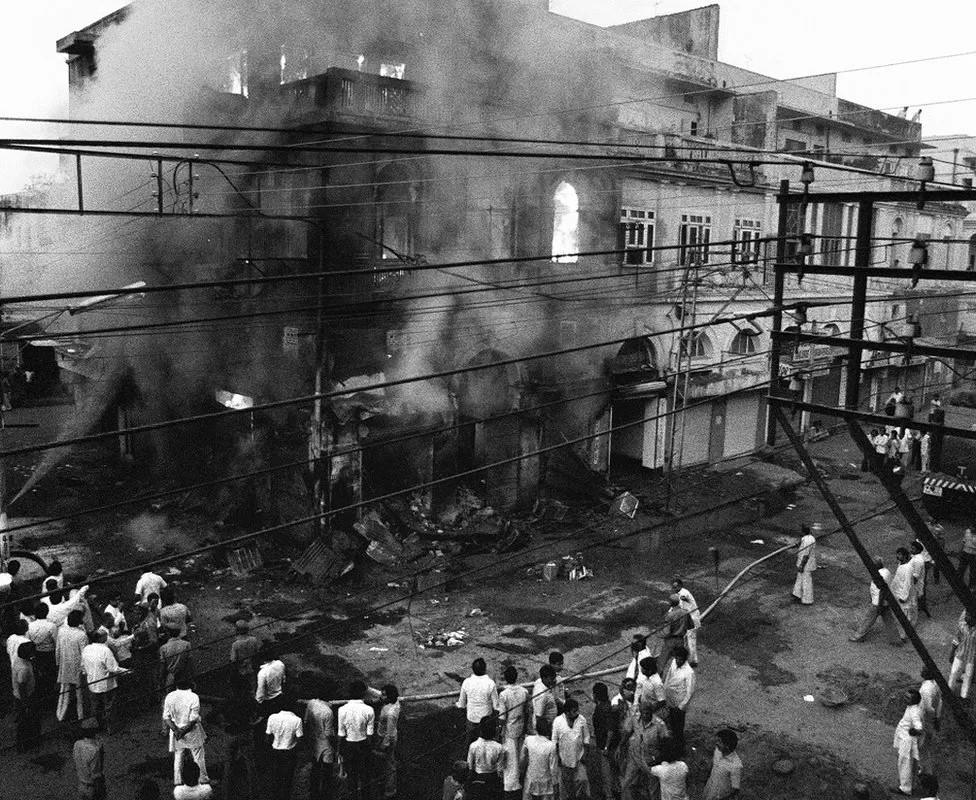

More than 1,000 people were killed in the riots in Gujarat in 2002

Violence has moved to the "centre stage of Indian public life", Thomas Blom Hansen, an anthropologist at Stanford University, argued two years ago.

He wondered why ordinary Indians seemed to either "tacitly endorse, or actively participate" in public violence. "This development signals a deep problem, a deformation and pathology that may present a danger to the future of democracy," Prof Hansen wrote in his 2021 book, The Law of Force: The Violent Heart of Indian Politics.

Amit Ahuja and Devesh Kapur, two US-based political scientists, differ. In their upcoming book, Internal Security in India: Violence, Order, and the State, they argue that large-scale violence has actually declined in the country. To put it more precisely, "aggregate levels of violence in India - public and private - have declined in the first two decades of this century compared to the previous two decades".

For their research, Prof Ahuja, of University of California, and Prof Kapur, of Johns Hopkins University, trawled through decades of official records of a swathe of violence in public life in India: from riots to election violence; from caste to religious and ethnic violence; from insurgencies to terrorism; and political assassinations to hijackings.

They found that violence in India has actually declined in many of these indicators - in some cases, substantially - during the "peak quarter century" from the late 1970s to early 2000s.

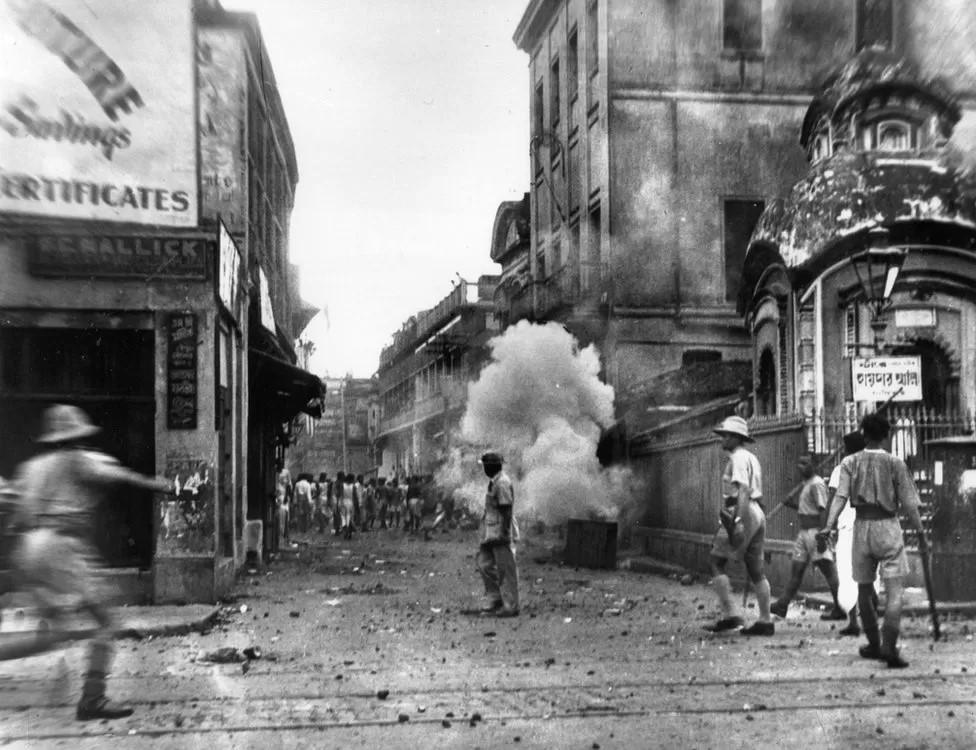

Some 2,000 people were killed in religious riots ahead of Partition in Kolkata (then Calcutta) in 1946

Some of their more striking findings:

Since 2002, India has not experienced any ethno-religious killings on the scale of the Gujarat riots in 2002, the 1984 riots in Delhi targeting the Sikh community or the 1983 killings of allegedly illegal immigrants from Bangladesh in Nellie, a small town in Assam. More than 6,000 people were killed in these riots alone. But Hindu-Muslim riots in the town of Muzaffarnagar in 2013 and in Delhi in 2020 - the two riots together claimed over 90 lives - are a warning that the "facilitators remain active, on tap, as it were", the authors suggest.

According to the Global Terrorism Index 2020, 8,749 people were killed in terror attacks in India since 2001. But such attacks seem to have declined since 2010. The number of terrorist incidents - excluding Kashmir - declined by 70% from 71 to 21 between 2000 and 2010 and the following decade.

Religious violence during the Partition of India claimed over a million lives and displaced an estimated 10 million. Hindu-Muslim violence was particularly deadly for about a quarter century from the late 1970s to 2002, when the Gujarat riots happened. Official data suggests that it has been relatively stable since. More than 2,900 cases of religious rioting were registered in the country between 2017 and 2021, the government told parliament in December.

From the 1970s to the end of the century, there was an almost fivefold increase in riots over the previous period. This began to decline by the late 1990s and saw an uptick between 2009 and 2017. When normalised by population, riots in India today are at a historic low, according to official data.

Electoral violence and high-profile political assassinations have declined. Two prime ministers, Indira Gandhi and her son Rajiv, were assassinated in 1984 and 1991 respectively. Violence at polling stations fell by a quarter and election violence-related deaths dropped by 70% between 1989 and 2019. This was despite elections becoming more competitive, a rise in the number of voters, and doubling in the number of polling stations.

Hewing to a worldwide trend, homicide deaths in India have declined over the past three decades. India's decline has been steeper - from 5.1 per 100,000 people in 1990 to 3.1 in 2018. Male homicide rates account for most of the decline; for women the decline was negligible.

There were 15 hijackings of Indian passenger planes in the three decades between 1970s and 1990s. There have been none since December 1999, when an Indian Airlines flight was hijacked on the way to Delhi from Kathmandu with 180 people on board.

Large parts of India were convulsed by four major insurgencies over the last four decades - Punjab during the 1980s and early 1990s, claiming more than 20,000 lives; and three other conflicts in north-eastern India, Kashmir and the Maoist violence in central and western India. The last three have simmered, but with a significant decline in violence beginning 2010. Incidents of left-wing extremism have declined by almost two-thirds between 2018 and 2020; and the number of civilian and security force deaths have declined by three-fourths during the same period.

Frequency of large-scale caste violence has diminished in the last couple of decades even though caste-based conflicts remain high.

Indira Gandhi's assassination triggered attacks on Sikhs and their properties across India

To be sure, there are different reasons for the decline in different kinds of violence.

Beefing up of state capacity has helped control insurgencies, riots and violence during elections. Increased use of paramilitary forces, using helicopters and drones for surveillance, installation of mobile phone towers, fortified police stations, new roads and increased health and education facilities in affected areas have helped stem the tide of this violence, Prof Ahuja and Kapur suggest.

"The decline of violence is more due to enhanced state capacity and less the sort of political settlements that would provide consent of the governed and ensure that new cycles of violence don't occur."

The decline in hijackings is generally attributed to the tightening of airport security around the world following 9/11. India's relatively strict gun laws seem to have helped to keep murders low. (60% of India's 3.6 million arms licences in 2018 were issued by just three states - Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir. Of course, there are illegal and smuggled weapons).

But there is a worrying outlier - the rising violence against women.

Although data is unreliable since much of it occurs in private spaces and goes unreported, reported violence against women has increased. About one in three women in India are subject to intimate partner violence, but only one in 10 of these women formally report the offence. There's growing harassment of women in digital spaces. Deaths over dowry continue to occur as do honour killings and acid attacks.

Prof Ahuja and Prof Kapur add some key caveats to their work.

For one, absence of evidence doesn't always imply evidence of absence. There is, for example, "violence and humiliation that curtail life opportunities of women and Dalits and religious minorities like Muslims".

Also, there has been a rise in new forms of public violence, stoked by communalism: intimidation and lynching to prevent interfaith marriages or cattle smuggling are the main concerns. "New forms of public violence such as vigilantism and lynch mobs seem to be sprouting like an ugly cancer across the country," say Prof Ahuja and Kapur.

What is worrying, they say, echoing Hansen, is why so many ordinary people support or participate in public violence. This "weakens a powerful check on the state" and also undermines the state's ability to control violence. "Online and street mobs are allowed to act with impunity. All this could easily spin out of control and significantly undermine state capacity to control violence."

Also, the decline in violence does not rule out its resurgence, they say. There could be an uptick in violence if social harmony is threatened, if joblessness and inequality worsen, and the ability to reach permanent settlements to political problems is delayed. "India has to do much more to reduce the threat of violence," they say.

Read more India stories from the BBC: