India budget focuses on tax relief and spending boost

- Published

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the budget in parliament on Wednesday

A sharp jump in capital spending, income tax relief to the middle class and efforts at financial discipline marked India's last full budget before the general election next year.

The BBC's Nikhil Inamdar on five key takeaways from the budget:

Infrastructure gets a spending boost

In line with the government's ramped up focus on building roads, highways and power plants since 2014, India's overall capital expenditure saw a sharp jump of 33%, which was marginally lower than the 35.4% increase budgeted last year.

But at $122bn, it marks a three-time increase over capital expenditure in 2019.

Money for railway projects saw the highest ever outlay of $24bn.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman also announced money for the construction of 50 new airports, aerodromes and heliports to improve regional connectivity, and increased spending on affordable housing projects by 66% to approximately $10bn.

Government reins in its fiscal deficit

The government has said it is targeting a half percent reduction in its fiscal deficit - the gap between what it earns and spends - from 6.4% in 2022-23 to 5.9% this year.

This will be done by increasing total spending at a moderate 7%, which analysts say could be challenging in a pre-election year.

But the finance minister reiterated her commitment to meet a medium-term goal of reducing the deficit further to under 4.5% by 2025-26.

India's fiscal deficit had swollen to a record 9.3% in 2020-21 as the government boosted spending on free vaccines and relief measures for the poor during the Covid-19 pandemic.

"The wriggle room for fiscal adventurism was always limited, so it is a matter of macroeconomic relief that the government has continued to opt for fiscal consolidation, while ramping up public capex, and still playing to the electorate gallery, particularly the middle class," says Aurodeep Nandi, India economist and vice president at Nomura.

Relief for the middle classes

Ahead of crucial elections in several states this year and the general elections of 2024, the government has announced tax relief measures for India's middle class.

This includes an increased threshold for personal income taxes for citizens who have opted for a new tax regime introduced in 2020.

Indians who earn under 700,000 rupees ($8,500, £6,900) will not have to pay income tax anymore if they migrate to the new regime.

India's maximum tax on personal income has also been effectively reduced from 42% to 39%.

The move is expected to boost consumption, as it will put money into the hands of people at a time when inflation has been eating into disposable incomes.

The finance minister said the new tax regime - where individuals cannot claim deductions on their investments - will be the default one, even though people could continue to use the old system.

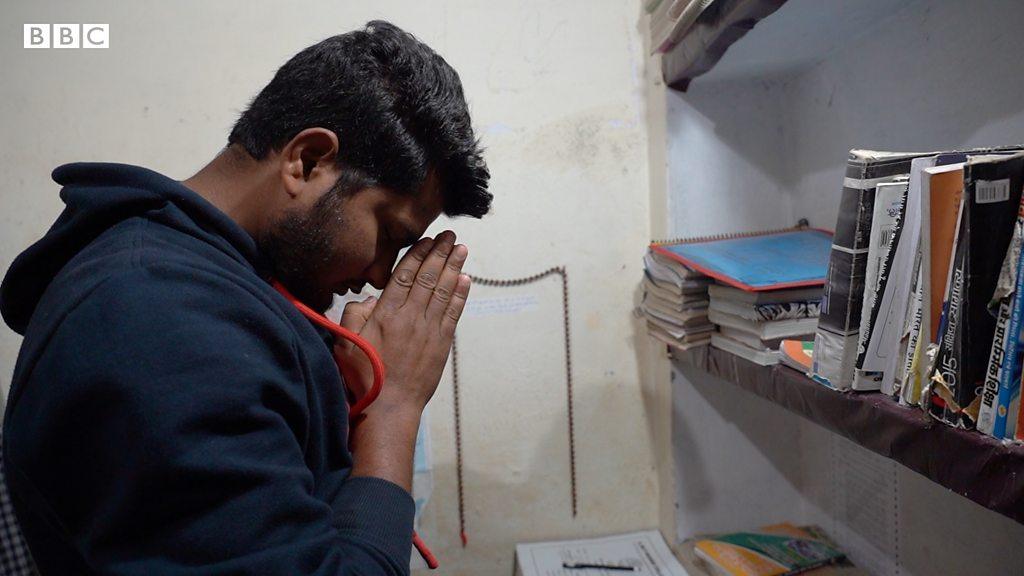

This is the government's last full budget ahead of the general elections in 2024

Reduced spending on welfare and subsidies to the poor

While there's relief for the middle class, the budget doesn't do much to improve the living standards of the country's most vulnerable. Spending on India's rural jobs programme, a crucial social buffer, has been slashed by over 30% at a time of high unemployment and delays in wage payments to workers.

The government has also discontinued a Covid-era free food programme, saving close to 30% on its overall food subsidy bill in comparison with last year's revised estimates.

Outlays for fertiliser subsidies to farmers are also down over 20%

Easing up the climate for doing business

But there's welcome news for small industries. The finance minister said the government has reduced 39,000 compliances for companies and decriminalised over 3,400 legal provisions.

A report last year, external had pointed out that India suffers from 'regulatory cholesterol' with over half the 1,536 laws that govern doing business in India carrying imprisonment clauses.

India has seen gradual improvements in the World Bank's ease of doing business rankings and is currently on the 63rd spot among 190 economies.

With a third of the world hovering on the brink of a recession after two pandemic years, India's economy remains a comparative bright spot in 2023.

GDP targets for the year have been moderated slightly, but India is expected to remain the fastest growing major economy in the world for a second year running.

Growth is likely to be in the range of 6-6.8%, according to the government's economic survey.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

Related topics

- Published7 January 2022

- Published24 February 2022