Chandrayaan-3: The race to unravel the mysteries of Moon's south pole

- Published

A passenger plane flying over the full Moon before landing in California in early August

The sun lingers slightly above or just below the horizon, while towering mountains project dark shadows.

Deep craters provide a haven for unending darkness. Some of these areas have been shielded from sunlight for billions of years. In these regions, temperatures plummet to astonishing lows of -414F (-248C) - because the Moon has no atmosphere to warm up the surface. No human has set foot in this completely unexplored world.

The Moon's south pole, according to Nasa, is full of "mystery, science and intrigue".

No wonder then that there's a so-called space race to reach the south pole of the Moon, far away from the Apollo landing sites clustered around the equator.

On Wednesday, India landed a robotic probe - Chandrayaan-3 - near the south pole. Three days earlier, Russia's Luna-25 crashed into the Moon while attempting the same feat.

India is also planning a joint Lunar Polar Exploration, external (Lupex) mission with Japan to explore the shadowed regions or the "dark side of the Moon" by 2026.

Why is the south pole emerging as a compelling scientific destination? Scientists say a key reason is water.

An image sent by Chandrayaan-3 show the craters on the lunar surface

Data gathered by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, external, a Nasa spacecraft that has been orbiting the Moon for 14 years, suggests water ice is present in some of the large, permanently shadowed craters that could potentially sustain humanity.

Water exists as a solid or vapour on the Moon because of the vacuum - the Moon doesn't have enough gravity to hold an atmosphere. India's Chandrayaan-1 lunar mission was the first to find evidence of water on the Moon in 2008.

"It is yet to be proven that the water ice is accessible or mineable. In other words, are there reserves of water that can be extracted economically?" Clive Neal, a professor of planetary geology at the US University of Notre Dame, told me.

The prospect of finding water on the Moon is exciting in many ways, scientists say.

The frozen water untainted by the Sun's radiation might have accumulated in cold polar regions over millions of years, leading to the accumulation of ice on or near the surface. This provides a unique sample for scientists to analyse and understand the history of water in our solar system.

"We can address questions such as where did the water come from and when, and what are the implications for the evolution on life on Earth," says Simeon Barber, a planetary scientist at UK's The Open University, who also works with the European Space Agency.

There are other "pragmatic" reasons for accessing water on or just below the Moon's surface, says Prof Barber.

A rocket carrying the lunar landing spacecraft Luna-25 blasts off from a launchpad in Russia on 11 August

Many countries are planning new human missions to the Moon, and the astronauts will need water for drinking and sanitation.

Transporting equipment from Earth to the Moon involves overcoming the Earth's gravitational pull. The larger the equipment, the more rocket and fuel load would be needed to achieve a successful landing on the Moon. The new commercial space companies charge around $1m to take a kilogram of payload to the Moon.

"That's $1m per litre of drinking water! Space entrepreneurs no doubt see lunar ice as an opportunity to supply astronauts with locally sourced water," says Prof Barber.

That's not all. Water molecules can be broken apart into hydrogen and oxygen atoms, and both can be used as propellants to fire rockets. But first scientists need to know how much ice is there on the Moon, in what forms, and whether it can be extracted efficiently and purified to make it safe to drink.

Also, some extremes at the south pole are bathed in sunlight for extended periods of time, up to 200 Earth days of constant illumination. "Solar power is another resource [to set up a lunar base and power equipment] potential that the pole has," says Noah Petro, a project scientist at Nasa.

The lunar south pole also sits on the rim of a massive impact crater of the solar system. Spanning a diameter of 2,500km (1,600 miles) and reaching depths of up to 8km, this crater is one of the most ancient features within the solar system. "By landing on the pole you can begin to understand what is going on with this large crater," says Dr Petro.

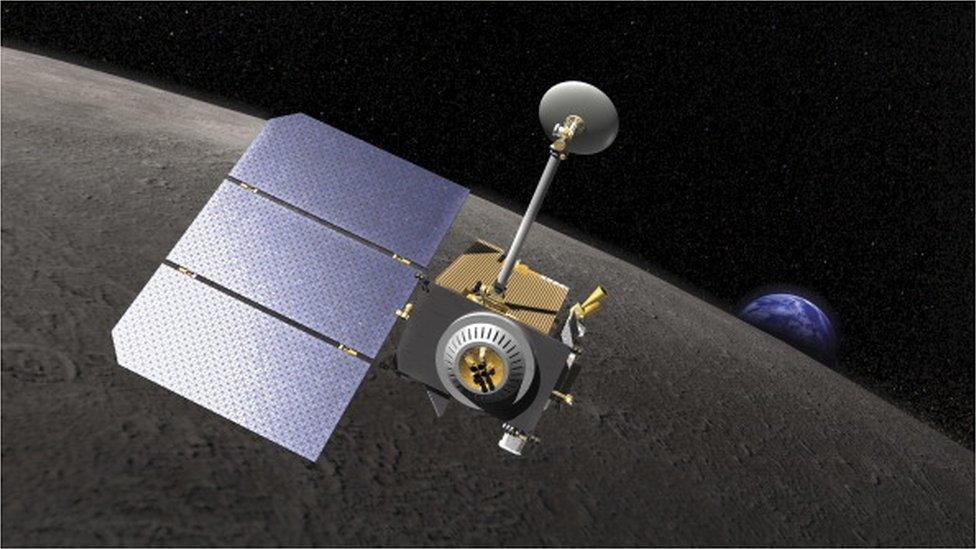

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a Nasa spacecraft, has been orbiting the Moon for 14 years

Navigating the lunar pole with rovers, space suits and sampling tools in a distinctly different light and thermal environment in contrast to previously explored equatorial sites also promises to yield valuable insights.

But scientists are chary of calling this a race to the south pole.

"These missions have been planned for decades and got delayed so many times. Race is not critical to our understanding of the Moon. The last time there was a real space race, we ended up losing interest in the Moon after three years and haven't returned to its surface in 50 years," says Vishnu Reddy, a professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona.

The Indian and Russian missions also had some common objectives, scientists point out.

Both aimed to land with similarly sized spacecraft in the south polar region, further south of the equator than any previous lunar mission.

Following an unsuccessful landing attempt in 2019, India wanted to showcase its capability for precise lunar touchdown near the pole. It also aims to examine the Moon's exosphere - an extremely sparse atmosphere - and analysing the polar regolith, an accumulation of loose particles and dust amassed over billions of years that rest above a bedrock.

Luna-25's objectives included the analysis of the polar regolith's composition, as well as an examination of plasma and dust elements of the lunar pole exosphere.

Nasa's Artemis programme aims to put astronauts back on the Moon, more than half a century after the last Apollo mission

To be sure, the landing site of the Indian orbiter is a "bit away from the actual pole". "But the data [it provides] will be fascinating," says Prof Neal.

Russia and China have plans to build a lunar space station to develop research facilities on the surface of the Moon, in orbit or both. Russia is planning more Luna missions. Nasa is sending instruments on commercial landers to go to places across the Moon. Japan is preparing to send a smart lander, external (the SLIM mission) on 26 August - a small-scale mission to demonstrate accurate lunar landing techniques by a small explorer.

And, of course, Nasa's Artemis programme aims to put astronauts back on the Moon in a series of spaceflights, more than half a century after the last Apollo mission.

"The Moon is like a giant puzzle. We have some of the pieces, the corners and edges based on samples and lunar meteorite data. We have a picture of what the Moon is like, but it is incomplete," says Dr Petro.

"The Moon is still surprising us."

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here, external to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: