Delhi AQI: Can artificial rain fix toxic air in India's capital?

- Published

Pollution is a recurring problem in Delhi

Could the answer to Delhi's pollution problem lie in the clouds?

Last week, as the Indian capital battled days of toxic air, the city's environment minister said that his government was considering cloud seeding - a rain-making technique - to bring down pollution levels.

The plan's fruition will depend on getting approval from India's Supreme Court, and possibly a number of federal ministries. If that happens, the scheme may be implemented later this month, depending on weather conditions.

This isn't the first time that cloud seeding has been suggested as a possible solution for air pollution in Delhi. But some experts say it is a complicated, expensive exercise whose efficacy in battling pollution is not completely proven, and that more research is needed to understand its long-term environmental impact.

But as Delhi's pollution keeps choking its people and making global headlines, political leaders seem desperate for a solution.

Anti-smog guns which spray water are among the tools used to fight pollution in Delhi

Over the past two weeks, the city's Air Quality Index (AQI) - which measures the level of PM 2.5 or fine particulate matter in the air - has consistently crossed the 450 mark, nearly 10 times the acceptable limit. And after a brief bout of (natural) rain brought down pollution over the weekend, air quality turned hazardous again on Monday as people burst firecrackers to celebrate the Diwali festival.

Pollution is a year-round problem in Delhi due to factors including high vehicular and industrial emissions and dust. But the city's air turns especially toxic in winter as farmers in neighbouring states burn crop remnants and low wind speeds lead to higher concentration of pollutants.

The Delhi government has announced school winter breaks early and banned construction activity. And it hopes that the Supreme Court, which is hearing petitions related to Delhi's toxic air, will give it the go-ahead for cloud seeding.

What is cloud seeding?

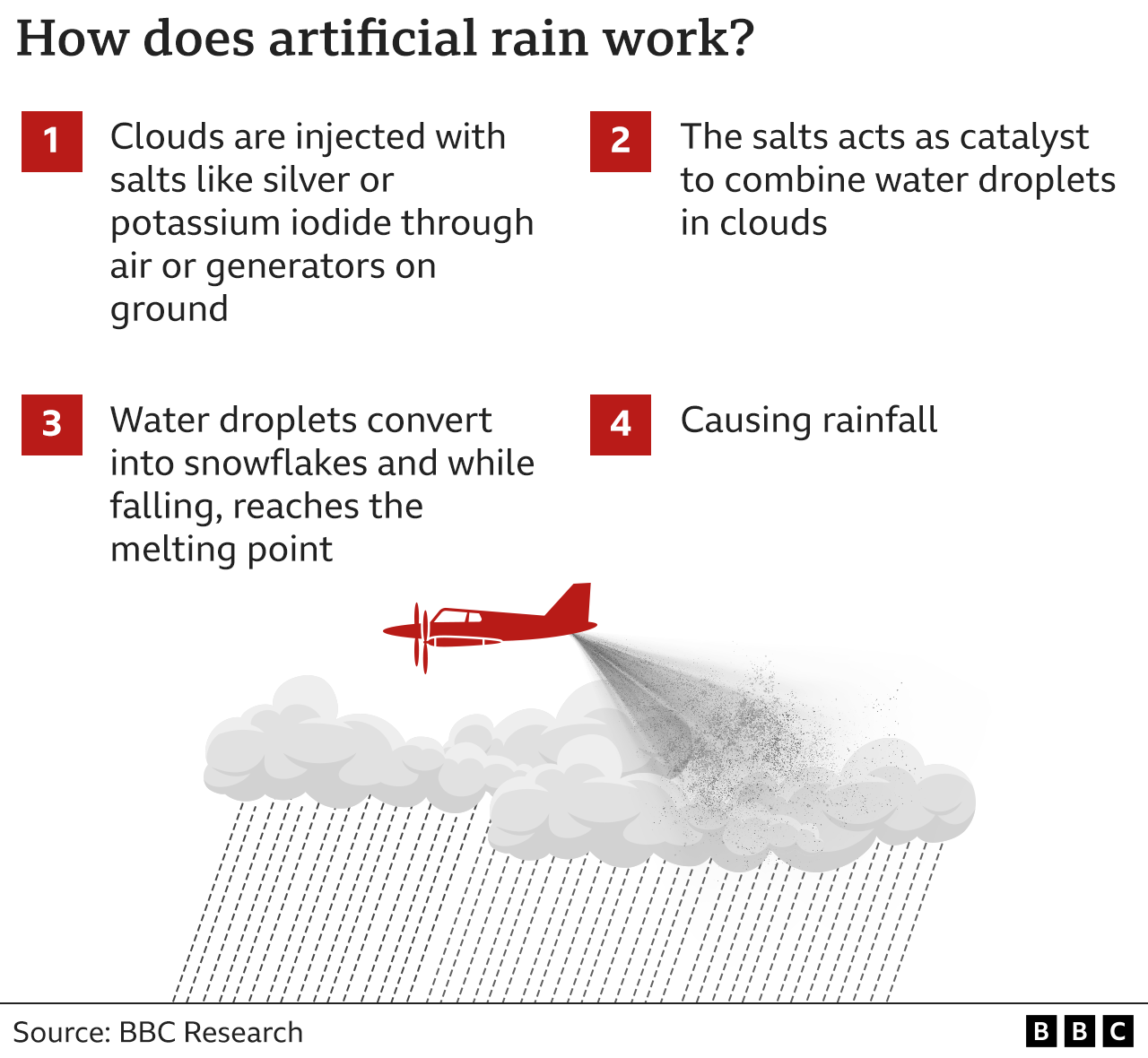

Cloud seeding is a technique that speeds up the condensation of moisture in clouds to create rain.

It is done by spraying particles of salt - like silver iodide or chloride - on clouds using planes or dispersion devices on the ground.

The salt granules act as ice-nucleating particles, which enable ice crystals to form in the clouds. The moisture in the clouds then latches on to these ice crystals and condenses into rain.

But the process doesn't always work.

Atmospheric conditions have to be exactly right, says Polash Mukerjee, an independent researcher on air quality and health.

"There should be the right amount of moisture and humidity in the clouds to allow for ice nuclei to form," he says, adding that secondary factors like wind speeds are also important - and they can be quite dynamic in Delhi at this time of the year.

The salt particles also have to be sprayed into a specific type of cloud that grows vertically as opposed to horizontally, JR Kulkarni, a weather scientist, told, external Down to Earth magazine in 2018.

This rain-making process has been around for decades. In fact, climatologist SK Banerji, external, the first Indian director general of the country's meteorological department, experimented with it in 1952.

In the 1960s, the US military controversially used the technique to extend the monsoon over certain areas in Vietnam to disrupt Vietnamese military supplies during the war.

Countries such as China and the UAE, and some Indian states have also experimented with the process to boost rainfall or deal with drought-like situations.

What does the Delhi government want to do?

The plan for the project has been submitted by researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kanpur, a top engineering college.

As per the plan, the project will be carried out in two phases, with the first phase covering about 300sq km (116sq miles). Experts have suggested that the project be implemented on 20 and 21 November as meteorological conditions will be ideal at the time.

Manindra Agrawal, the scientist leading the project, told Reuters, external that while they didn't expect enough clouds to cover Delhi fully on those days, "a few hundred kilometres would be good".

And can it really help with pollution?

The rationale is that rainfall may help wash away particulate matter in the atmosphere, making the air cleaner and more breathable.

Delhi experienced this first-hand last week after brief spells of rain on Friday and Saturday brought down pollution levels.

But experts say it's not clear how helpful artificial rain will be.

Mr Mukerjee says that cloud seeding has been used for air quality management and dust suppression in other countries, but these have been "episodic at best".

"If you look at the impact of rainfall on air quality, it immediately brings down pollution levels, but the levels stabilise and bounce back within 48-72 hours. Cloud seeding is expensive and diverting scarce resources towards an activity that does not have definite or lasting effects is a band-aid solution," he says.

He adds that it must be a matter of deliberated and discussed policy. "It cannot be an ad-hoc decision. You must have a series of protocols in place and a multi-disciplinary team making them, including meteorologists, air quality policy experts, epidemiologists, etc."

Some experts are also concerned about what we don't know yet about the process.

"Right now, there is no substantial empirical evidence on how much the AQI is going to come down by cloud seeding," says Abinash Mohanty, a climate change and sustainability expert.

"We also don't know what its [cloud seeding] effects are because in the end you're trying to alter natural processes and that's bound to have limitations," he adds.

According to him, pollution can't be solved just by using "meteorological variables like rainfall and windspeed".

"We need to make more concerted efforts to curb air pollution than scattered trial-and-error experiments."

Additional reporting by Zoya Mateen

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here, external to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

Related topics

- Published6 November 2023

- Published14 June 2022