JS: The iconic magazine which 'invented' the Indian teenager

- Published

JS captured the zeitgeist of India's urban young in the troubled 60s and 70s

The nearly-forgotten JS, a cult youth magazine from the 60s and 70s, uniquely shaped the Indian teenager. The BBC's Soutik Biswas explores its near-defunct archives, revealing a magazine that vividly captured the hope and desperation of those decades in India with depth, wit, and vitality.

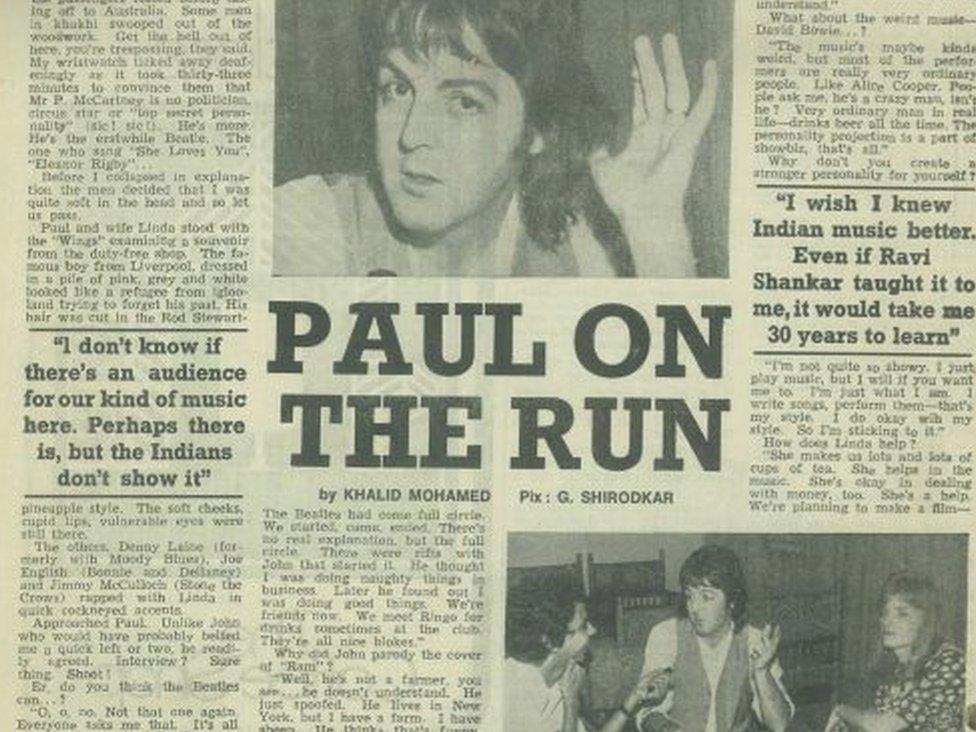

In 1975, intrepid Indian journalist Khalid Mohammed sneaked into Mumbai (then Bombay) international airport's transit lounge armed with a tape recorder, to meet Paul McCartney en route to Australia with his band, Wings.

The result was an interview brimming with drollery and repartee, as they talked about the rumours of a Beatles reunion, the future of rock music, and life with the Wings.

At one point, Mr Mohammed asked McCartney whether his music was becoming increasingly commercial.

"Our next album won't be commercial. It'll be experimental. Twenty-minute songs and backwards - just for you," the ex-Beatle quipped.

The freewheeling McCartney "scoop" epitomised JS, derived from Junior Statesman, a pathbreaking sibling to a prominent and upstart Kolkata-based (then Calcutta) newspaper. "Anyone who was a teenager in India between 1967 and 1977 will not need persuading about the extraordinary impact that JS had on their generation," Shashi Tharoor, MP and author, told me.

JS sneaked into the Mumbai (then Bombay) international airport's transit lounge to meet Paul McCartney

Mr Tharoor should know. He made his writing debut at the age of 11 with a six-part World War Two adventure in JS, earning a "princely sum" of 50 rupees. "I still meet middle-aged matrons who wax eloquently about the magazine, including people who can quote back at me from memory things I'd forgotten I'd written."

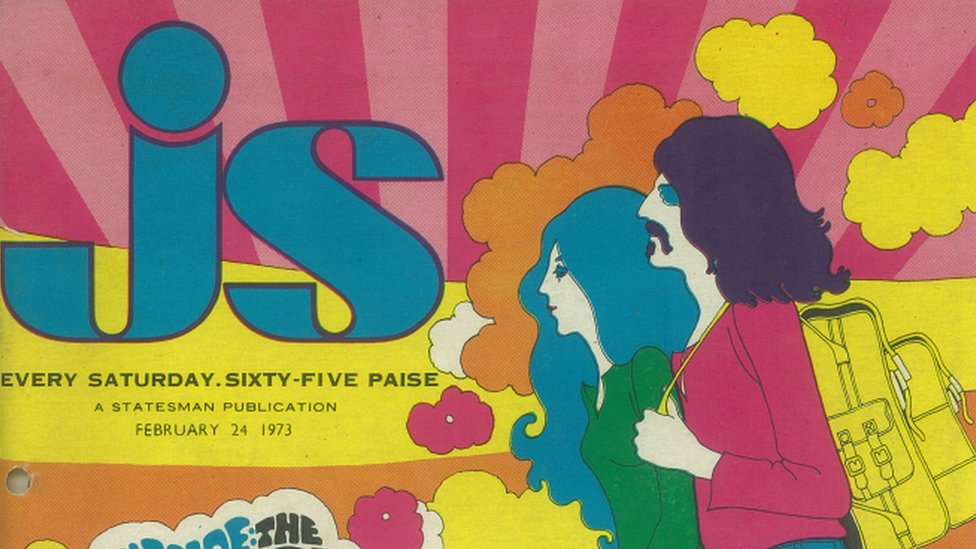

When JS exploded onto the scene in February 1967, featuring The Beatles on its first cover, it quickly captured the zeitgeist of the urban youth of a nation grappling with shortages, rising prices, and joblessness. It was a grim and austere time. There was no TV, save a lone, uninspiring black-and-white channel; the young read books and listened to music, while most papers and magazines were pedantic and mundane.

Under the leadership of Desmond Doig, an India-born Anglo-Irish artist and writer, and previously a roving reporter for The Statesman, JS magazine was run by a bunch of enthusiastic college graduates. It swiftly gained a reputation as an irreverent, chatty, insightful magazine, always engaged with its reader.

"Before JS, it was assumed that children became adults overnight. JS recognised that there was a whole in-between identity with its own canon," says journalist and author Bachi Karkaria, who made her writing debut in the magazine as a teenager.

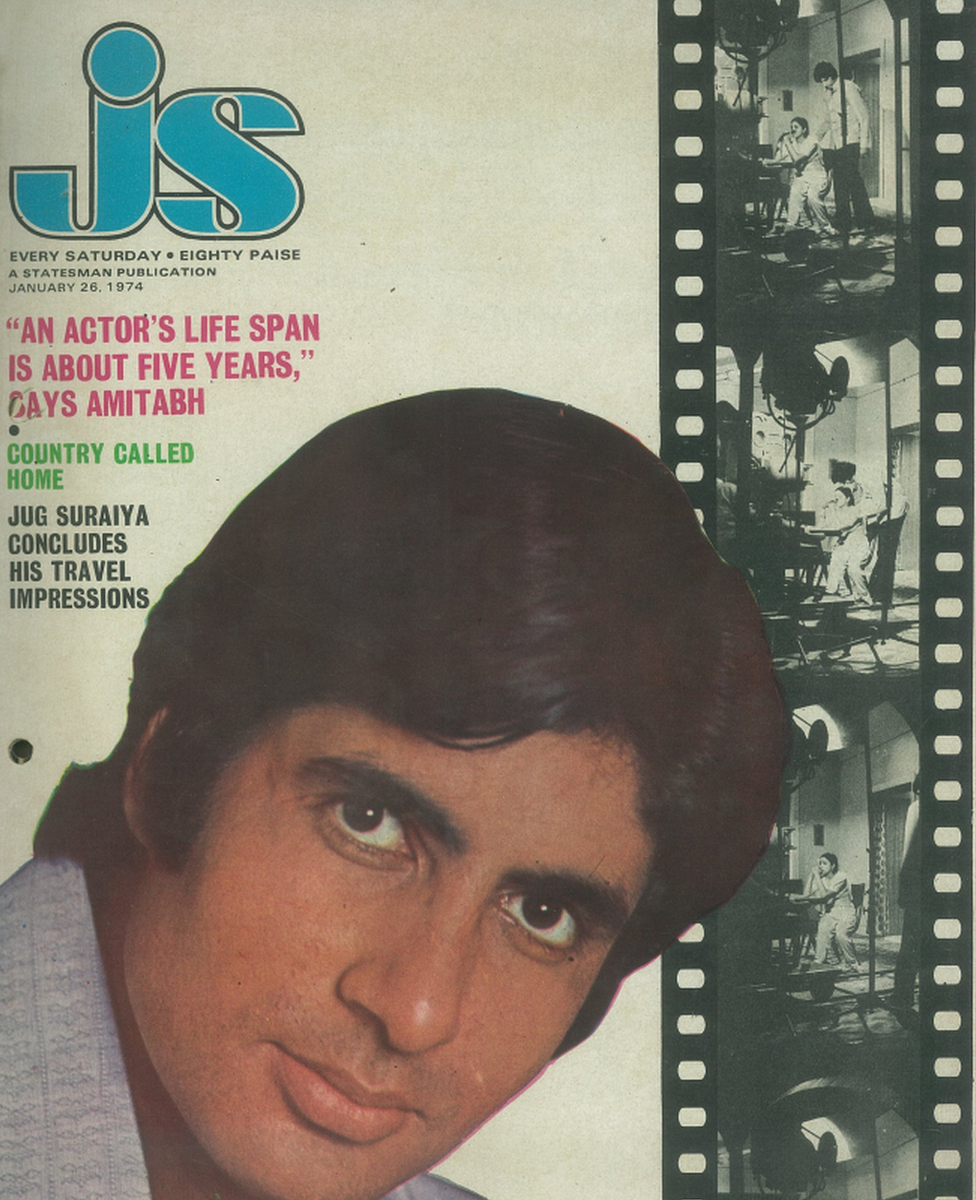

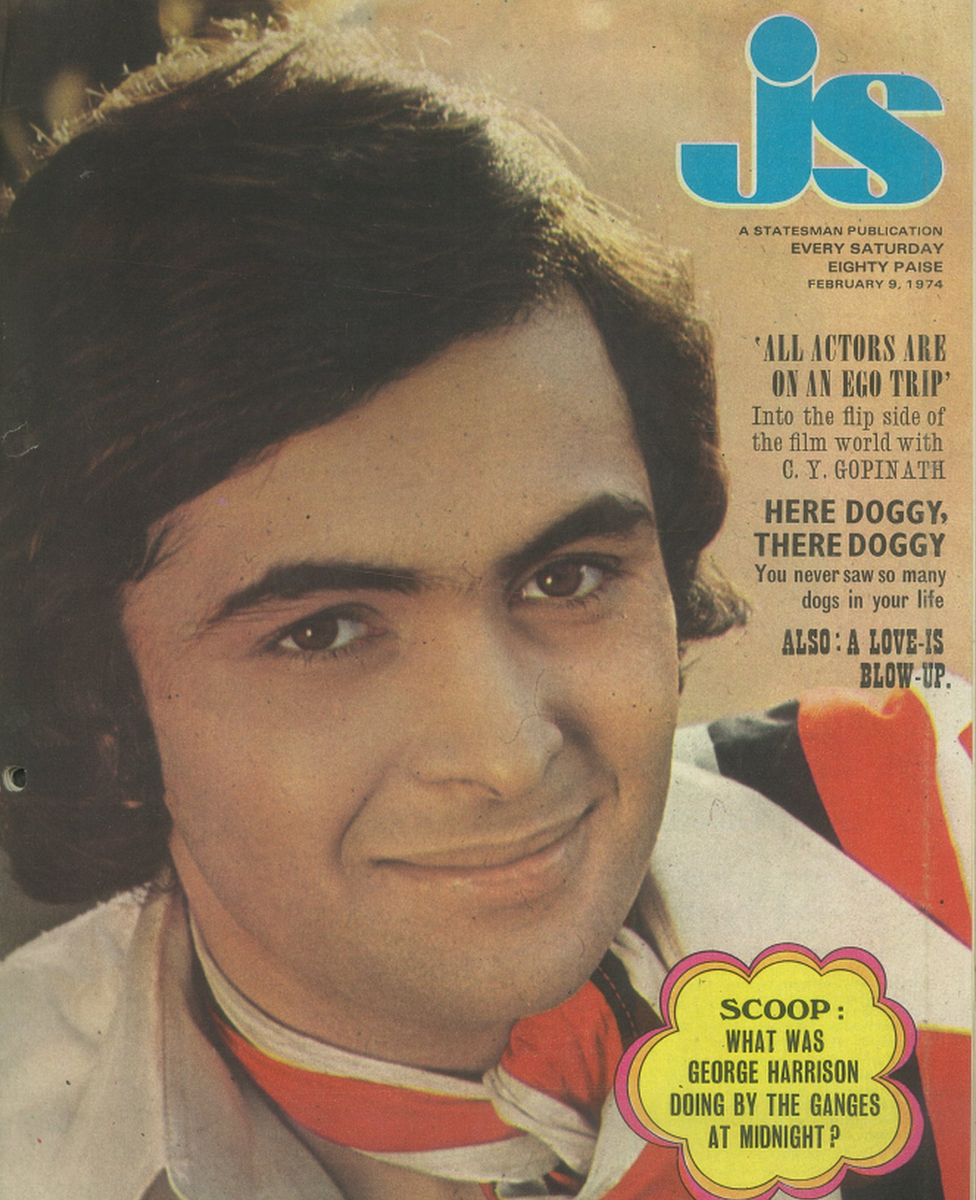

The colourful weekly covers were a vibrant blend of the global and local: kaleidoscopic pop-art illustrations; images of Bollywood stars such as Amitabh Bachchan and Rishi Kapoor cheek by jowl with those of Led Zeppelin and the Beatles; and the exuberant colours of the folk arts of Bihar state. A special attraction were large fold-outs of teen icons. "JS wasn't just a magazine, it was a happening," wrote Jug Suraiya, a prolific writer for the magazine, in his memoirs.

'We are not very rich people,' Amitabh Bachchan told JS, which spent four days with the actor for a cover story

And Bollywood heartthrob Rishi Kapoor told JS that he was 'in love all the time'

Quirk was always a few covers away: The Day The Martians Landed, screamed one headline, with two alien spaceships looming dramatically; or ESP: Fact Or Fiction, as part of a series of "eternal controversies". The sensibility of the articles, according to Mr Tharoor, "alternated between Seventeen magazine and Hunter S Thompson, external on a (relatively) sober day."

Not surprisingly, there was seldom a dull moment.

In 1975, helped by "unimpeachable sources" JS "surreptitiously" tracked down George Harrison in Kolkata, where's he was on a 30-hour-visit as part of a "pilgrimage of holy places" in India.

CY Gopinath, the magazine's meticulous reporter, wrote that the music superstar spent time meditating, going through "yogic postures", "counting beads on a rosary", visiting temples, ordering an image of Hindu goddess Kali, and having Bengali food for lunch at a friend's place.

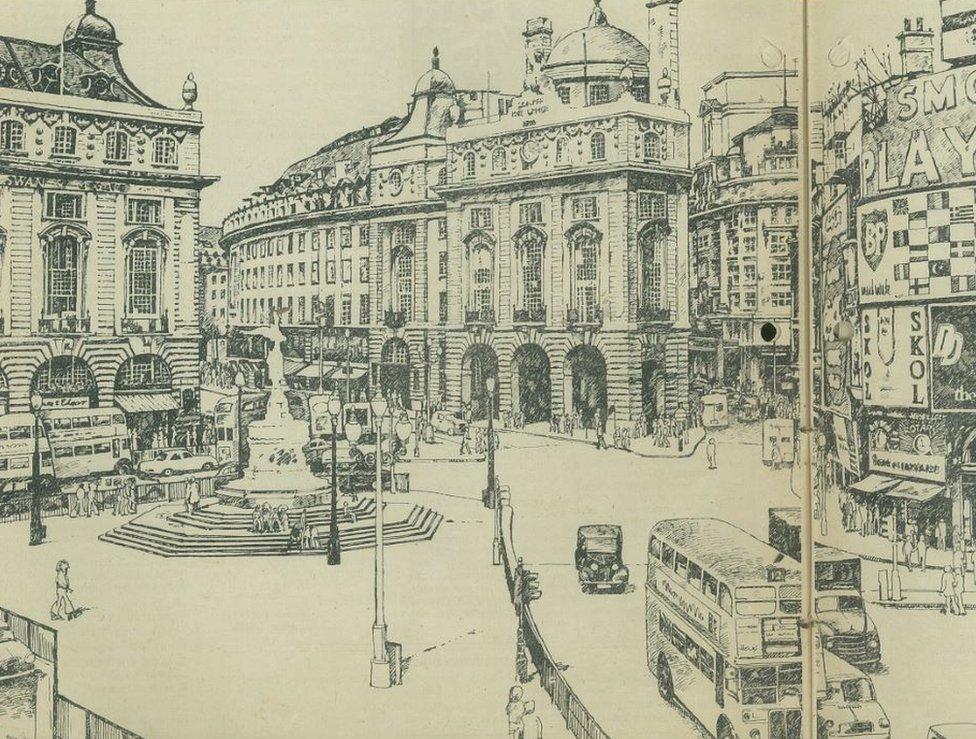

A serialised London travelogue carried this illustration by JS artist Deb Mahalonobis

He even managed to snatch a two-minute conversation during which Harrison answered half a dozen questions, had seven pictures taken, and gave an autograph. The magazine carried a picture of the long-haired musician with the caption: "George Harrison has gone Hindu pilgrim."

There was no dearth of controversies. Fusion music pioneer Asha Puthli, crestfallen after a concert in Mumbai in the aid of the hungry, told the magazine that most of the audience "seemed more interested in eating 'phoren' (foreign) food".

"To add to it, the sound system was bad. I actually cried, you know."

Then there was Bollywood. "We are not very rich people," Amitabh Bachchan told JS, which spent four days with the actor for a cover story. Mr Gopinath, the keenly observant correspondent, wrote he didn't quite believe the star because he saw the "Toyotas and Merces in [his] leafy driveway, the smell of Aramis after shave in the crowded make-up room, the numerous packs of Dunhill cigarettes, the lunchtime talk of days spent shopping in Piccadilly [Circus]".

JS was also ahead of its times in many ways. At a time when few Indians could afford to travel abroad, the magazine went to New York and London, publishing long travelogues with illustrations and pictures - "If London can surprise with serendipity, New York can baffle with elusiveness," said a florid piece.

Years before leading newspapers started inviting celebrities to guest-edit for a day, JS gave actor Jalal Agha the reins as editor "for half an hour". During this brief stint, Agha playfully "stomped around the office like a crazed, plump Bugs Bunny, causing havoc, despair, and semi-permanent damage" - a whimsical episode vividly captured in a series of gleeful pictures.

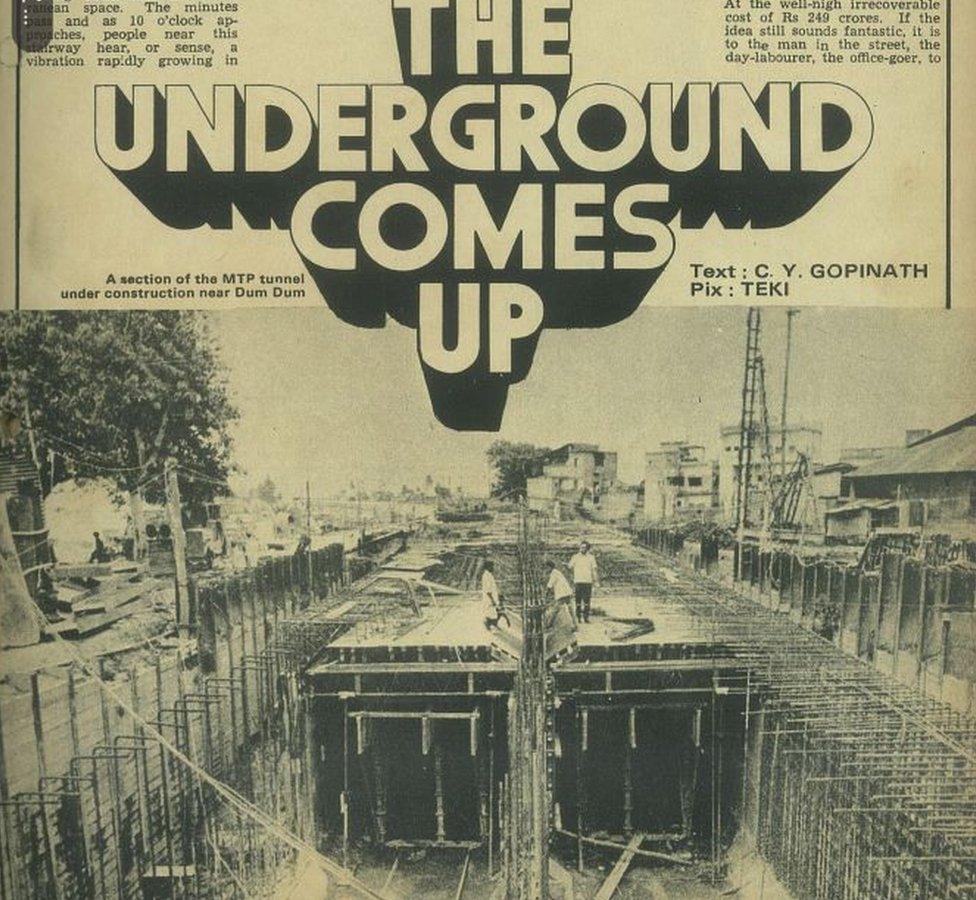

In 1976 JS did a deep dive into India's first underground metro in Kolkata which took 12 years to build

At a time when vivid reportage in the mainstream media was scarce, JS reporters filed reports from far-flung places making hand-woven carpets, denims and silk saris. JS covered the Dalit Panthers' efforts to break caste barriers in Bombay, sent reporters to rain-drenched Naxalbari to cover a 1967 Maoist rebellion, and travelled to Bhutan for the coronation of a new king.

To find out how the other India lived, JS spent a few days in a dusty hick town in central India. Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh, as described by the magazine in 1975, had "a dusty, crowded cow-dung splattered bazaar, small stucco houses and a social hierarchy as rigid and fierce as the summer heat".

In 1976, the magazine carried a deep dive into India's first underground metro, being built in Kolkata - the metro took 12 years to build. The prolonged excavation found "an old pair of handcuffs, a number of bullet shells, believed to be some wide misses from some World War II target practices, and a handful of not-very-old gold coins". There were rumours of gold being found. Dug up neighbourhoods appeared "temporarily anaesthetised, deprived of life blood".

Long before shouty TV debates became a TV staple, JS featured periodic faceoffs between opposing views. Preceding the trend of opinion polls, it introduced 'We took Ten,' where 10 randomly chosen young people voiced their opinions on various topics. And long before celebrities became media contributors, Bollywood's Rekha, Zeenat Aman, and Simi penned beauty and advice columns for JS.

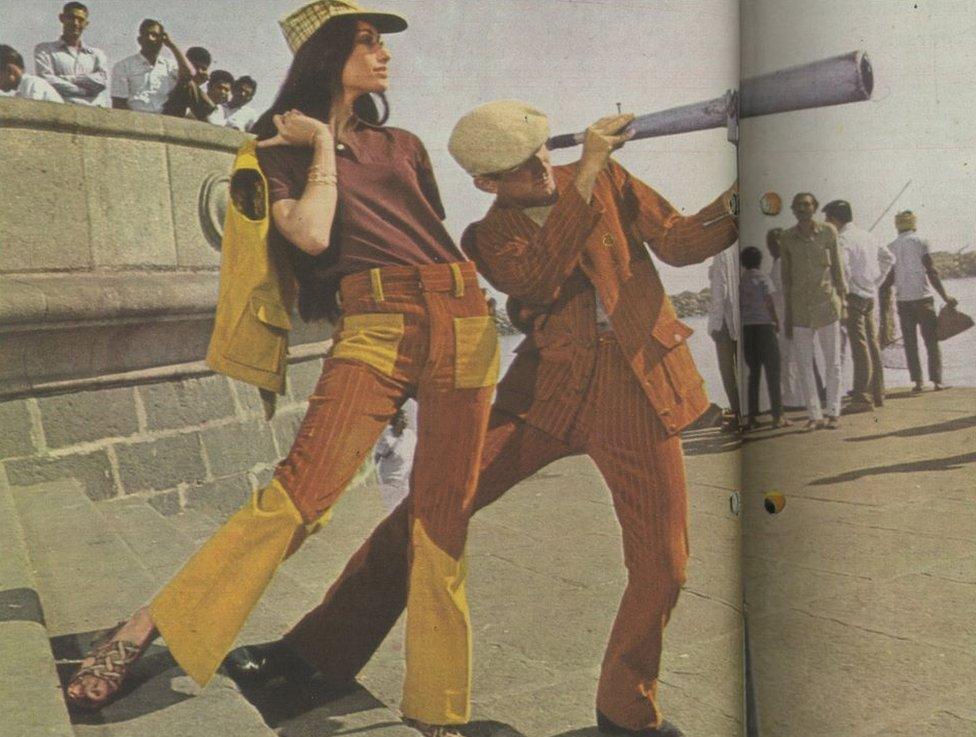

A fashion spread in the magazine in 1974

The 60-page weekly was packed with surprises. It organised events called 'JS Happenings' where its mascot, a 1932 Ford vintage car painted in psychedelic colours, would be displayed. Then there was a barter column called JS Exchange. "Sixteen, female, likes Ravi Shankar, Rolling Stones and Rajesh Khanna. Wants friends with similar interest for picnics, parties etc. Parent-approved boys acceptable," read one post.

Critics sneered that JS was "frothy and un-Indian, that it encouraged young Indians to 'ape the West' by wearing jeans and listing to pop music". Mr Suraiya spiritedly defended the magazine: "JS spoke to a certain urban educated cultural sensibility that was in a sense, Westernised, but it was shaping a distinctly Indian cosmopolitanism".

The end came brutally and abruptly, out of the blue in 1977, for reasons that are still not clearly known. Despite having around 40,000 paid subscribers and numerous readers, The Statesman chose to cease publication of its sibling, hastily halting the presses during the printing of an issue featuring a cover story on tea gardens. "JS crystallised what it meant to be an Indian teen - and left that class floundering when it was unceremoniously, even pettily shut down after creating a never-before-genre of journalism," Ms Karkaria said.

Mr Suraiya, the magazine's most prolific and peripatetic writer, wrote the epitaph for a dream that died young.

"If I had to use one word to describe the JS it would be Camelot. The promise of a once and future kingdom, the kingdom of youth."

"We shall always remember when we were young. And when young no longer, we shall know that youth itself always lives on. Forever ending, forever enduring, with its astonishment, and its anger, and its pangs of joy sharp as pain. That is what JS was, and is, and always shall be."

With inputs from singer-songwriter Jaimin Rajani and Chandni Doulatramani

Related topics

- Published25 February 2023

- Published13 September 2020