Asylum: Australia's 'toxic' election issue

- Published

Illegal arrivals are few in comparison to skilled and sponsored migrants, but have caused wide concern

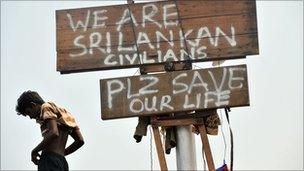

Holed up in the dark stinking hull of a wooden fishing boat, Amalan, a Sri Lankan Tamil refugee, made a "nightmare" voyage to Australia.

The 29-year-old had paid people-smugglers $15,000 (AU$16,600; £9,600) to help him escape his country's brutal civil conflict.

The smugglers had promised him a short journey across the Indian Ocean. In the end he spent 30 days at sea.

Three people out of the 76 crammed on the rickety vessel died during the crossing.

"There were no facilities on board, no safe place. We just sat. People fell ill with fever, vomiting and diarrhoea."

Food and water ran out in the final few days, Amalan says; they eked out just enough for the children.

Amalan's experience is not unique. Thousands of Asian asylum seekers like him have attempted to reach Australia's shores - sparking a fierce debate that is now a major election issue in Australia.

Tough stance

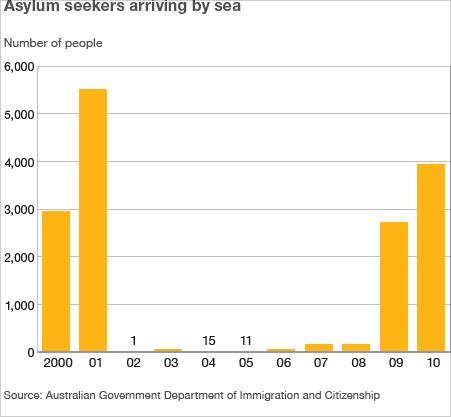

So far during 2010 Australian authorities have stopped 82 boats carrying 3,934 asylum seekers - an increase of more than 1,000 on the total figure for 2009.

The country's Department of Immigration says more than 2,000 are being processed on Christmas Island, an Australian territory. The rest are in detention centres on the mainland.

The illegal arrivals have caused anxiety, stoked by alarmist tabloid headlines and opposition calls to "stop the boats".

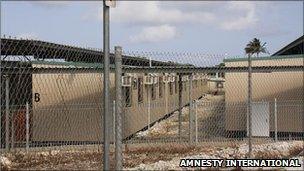

Human rights groups say arbitrary long-term detention can lead to mental health problems

Australia's Prime Minister Julia Gillard has sought to appear tough on the issue.

During the tenure of the former, conservative, government, Ms Gillard condemned as a "costly and unsustainable farce" the so-called Pacific Solution: sending asylum seekers to neighbouring Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

But her proposed alternative - to set up a processing centre in East Timor - sounds remarkably similar.

Her rhetoric is slightly different in that she wants the burden of accepting refugees to be shared by other countries in the region. She has sold the idea as a "regional protection framework", saying: "The purpose would be to ensure that people smugglers have no product to sell."

But Ms Gillard's plan is already in serious doubt after East Timor's parliament voted in July to reject it.

Opposition Liberal Party leader Tony Abbott has been quick to jump on the government's vulnerability, promising a return to the Pacific Solution.

"I have a simple message to the Australian people - if you want to stop the boats you've got to change the government," he said, unveiling his own immigration policy on the heels of Ms Gillard's.

Analysts say the issue is a toxic one for the government, and has been muddied by being linked to immigration and population growth.

"There is some public confusion... these different issues have become confused - the number of boat arrivals is so miniscule that it is irrelevant to population growth," says political analyst Martin Drum of the University of Notre Dame in Western Australia.

A significant number of Labor party voters are sympathetic to the plight of asylum seekers, he says, but suggests there are also swing voters in key marginal constituencies, which puts the government in a difficult situation.

"At the heart of this issue is the notion of control; political parties define the problem as 'border protection', painting asylum seekers as a threat - this is what makes voters nervous.

"Rather than put the facts out there, political leaders pander to this sentiment and by doing so they legitimise it," he says.

Australia has a current annual intake of 13,750 asylum seekers under its humanitarian programme.

Of those, 6,000 are refugees from overseas referred to Australia for resettlement by the UN's refugee agency - for example Iraqis in Syria or Burmese in Thailand.

The other 7,750 places are allocated as part of its special humanitarian programme. An example would be a foreigner living in Australia whose wife overseas was at risk of human rights abuse.

Those entering Australia illegally by boat or plane take the places of those who could otherwise be granted asylum under this programme.

From here comes the term "queue jumper": onshore arrivals often portrayed by politicians as less deserving, according to Graham Thom, Amnesty International Australia's Refugee Co-ordinator.

But some have no choice other than to flee persecution, Mr Thom says.

"The notion that the country is being swamped is a nonsense. The figure of 13,750 will not change; there is in fact an enormous amount of control.

"We do have the capacity to deal with the arrivals and we are obliged under the UN Refugee Convention, to which Australia is a signatory, to make a humanitarian response."

Human rights groups have deplored as "appalling" and "absurd" the Labor and Liberal proposals to move the processing of refugees to East Timor or back to Nauru.

They say there is no evidence to support politicians' assertions that offshore processing centres act as a deterrent to would-be asylum seekers.

Instead they say it is counter-productive, setting a poor example to other Asia-Pacific countries that it is ok to turn the boats around.

Interrogation

The Liberals have used the significant drop in boat arrivals under the Pacific Solution as justification for their policy to re-open Nauru.

But Elaine Pearson, head of Human Rights Watch Asia Division, says the figures from 2002 to 2008 are misleading.

"The figures do not document how many boats were turned away. Of those that were sent to Nauru, many of the refugees ended up in Australia eventually - the route was just more traumatic and expensive."

Human rights groups are also concerned by the current government's decision to suspend the processing of Afghan refugees for six months, saying that long-term arbitrary detention can lead to people breaking down.

A three month suspension of the processing of Sri Lankans was recently revoked.

Amalan, who was granted refugee status this year and is now settled in Sydney, says he was lucky to have spent only 10 months on Christmas Island.

"It's a kind of prison. Immigration and other security agencies put us through at least two interviews a week, questioning us over and over about smugglers and terrorist links.

"Many people are suffering depression and having to take medication to cope. This is one way to block out the trauma but it is not a solution," he said

The Australian Department of Immigration said it was not able to comment on these issues given that campaigning was under way.

Comment was sought from the office of Immigration Minister Chris Evans, but there was no immediate response.

With both major parties in apparent agreement that boat people should be processed elsewhere, the ballot box battle may simply come down to who talks toughest on asylum.

Amalan's name was changed to protect the identity of his wife and child, who remain in Sri Lanka.

- Published15 December 2010

- Published19 August 2010