Japan moves on from the Cold War

- Published

Japan is seeking to bolster ties with the US

Japan is reshaping its defence in response to the shifting balance of power in Asia.

Nearly two decades after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country's strategic posture is moving out of the Cold War era.

The National Defence Programme Guidelines, which will shape policy for the next 10 years, point to China and North Korea as a bigger threat than Russia.

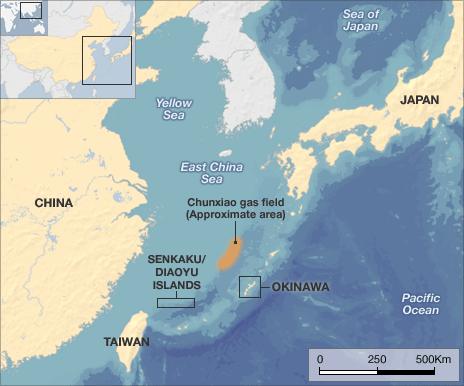

Relations between Japan and China have been strained since a territorial dispute over the Senkaku islands (known as the Diaoyus in China).

It began in September when Japan's coastguard arrested a Chinese fishing captain whose vessel had collided with two Japanese patrol ships.

Japan had long been eyeing China's growing military power with anxiety, particularly its increasing activity at sea around the country's southern islands.

"These movements, coupled with the lack of transparency in its military and security matters, have become a matter of concern for the region and the international community," the defence review stated.

In response Japan is realigning its resources from the north - where armoured formations were deployed against the threat of invasion by the Soviet Union - to the south.

North Korean missiles

The key shift is from conventional, heavy force to more flexible units.

The number of tanks and artillery pieces will be cut, while the submarine fleet is expanded.

"The Chinese military expansion is not only on the sea, or in the sky, or on land, but directly influences Japanese sea communication [with] the Middle East," said Toshiyuki Shikata, retired Lieutenant General and corps commander of Japan's northern army, now a professor at Teikyo University.

Japan is moving away from tanks and artillery to concentrate on the navy

"We do not have any concern about their land forces, only maritime forces like the navy and missiles. A drastic expansion of that kind of capability could be a threat in the future."

Another concern for Japan is North Korea, which has fired several missiles over the country in recent years, and launched an artillery attack on South Korea last month.

Its missile and nuclear programmes are described by the Japanese review as "a present and grave destabilising factor to the security of our country and the region".

Under the plan, Japan will increase the number of Patriot missile interceptor batteries deployed across the country.

The number of warships equipped with the Aegis ballistic missile defence system will be increased from four to six.

Asia watches

Japan's military is bigger than Britain's, but it is forbidden from engaging in offensive action by the country's post-World War II constitution.

For 50 years Japan has been in a security alliance with the US.

The relationship was frayed after the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) came to power in 2009, ending half a century of conservative dominance.

Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama tried to fulfil an election pledge to move an unpopular US marine base from the southern island of Okinawa.

When he failed, he resigned.

The new defence guidelines describe the alliance as indispensable and call for it to be strengthened.

"It's an admission from the DPJ government that the brief attempt to change the paradigm and to reach out for closer ties with Japan's neighbours, or even the Hatoyama concept of an East Asian Community, has been put on the shelf," said Koichi Nakano, associate professor of political science at Sophia University in Tokyo.

"With what has happened with China and North Korea, the DPJ government came around to the idea that strengthening of the US-Japan alliance is what needs to be done at this juncture."

Current Prime Minister Naoto Kan has said the new defence guidelines should not alarm Japan's neighbours.

But the shifting strategy will be closely watched in Asia, where Japan's wartime aggression has been neither forgotten, nor forgiven.

- Published17 December 2010

- Published10 November 2014

- Published21 September 2010

- Published3 November 2010