Beijing school closures shut migrant workers out

- Published

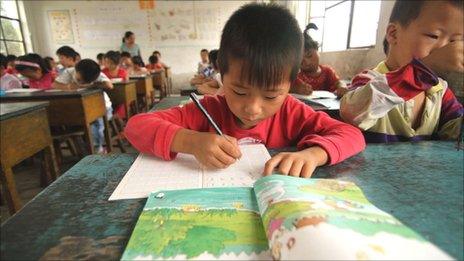

Children of migrant workers are often denied access to state-funded education

Children across China are now back at school after the summer holidays - but several thousand in Beijing are still fighting for a place to study.

With no warning, education officials decided to close down 24 schools for the children of migrant workers just weeks before the start of term.

They say they will provide places at state-run schools for these pupils, but it is still unclear whether that will happen.

Meanwhile, angry parents - many who helped build the schools themselves - wonder what will happen to their children.

Some think that closing down the schools is part of a wider plan to force migrant workers out of China's capital city.

Migrant workers are people who move from the countryside to towns and cities to find better-paid work.

But because of China's complicated household registration (or hukou) system, most have access to services - like health and education - only in their home villages.

They receive little help from the authorities in their new homes.

This status - which many liken to being a second-class citizen - is something the central government has long promised to reform.

They have not yet done so, forcing many migrant workers to take matters into their own hands and build their own schools.

At the end of July, Beijing decided to close two dozen of these in three districts - Haidian, Chaoyang and Daxing.

There was no consultation: schools were simply sent terse notices ordering them to shut down.

"Local government departments carried out an investigation at your school," read the one sent to Dongba Experimental School in Chaoyang district.

"The investigation found that the buildings, the fire prevention plan and the electricity supply all had serious hidden dangers and hygiene problems."

It ordered the school to stop teaching activities "from the day you receive this notice".

'Question mark'

The teachers were flabbergasted.

The Dongba school has been operating from its current location since 2003 - after being built by money loaned from the migrant worker community.

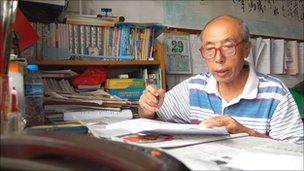

Head teacher Yang Qin says he does not understand why his school is being closed

Its running costs are met from the fees paid for by the students - there were about 1,300 of them for the last academic year.

The authorities have given nothing to the school.

Yang Qin, Dongba's head teacher, wants the authorities to come back to the school and check out its facilities again, but he cannot get anyone to answer the phone at the local education department.

In the meantime, he has decided to open for business as usual.

"We're open! Students are welcome at the school," read a notice chalked on a blackboard and placed outside the school gates.

But across the road there was another sign, placed by the authorities, saying the school has been ordered to close down.

There has been a stand-off between the school and the local government for several weeks.

Officials cut off the water and the electricity; the teachers responded by bringing in a generator and getting water from nearby homes.

"The question mark in my head is huge. Why are they doing this? Why do they want to close us down?" said head teacher Mr Yang.

'Make life difficult'

That is a question being asked by many people.

Officials are reluctant to be interviewed about their motives, but they say they are simply trying to provide children with a better education.

The migrant children will be able to go to state-run schools, they say.

Mother Wu Fang says people like her have no power and have to accept the authorities' decisions

But providing adequate places for thousands of children just weeks before the new term - when those places did not exist before - will be challenging.

Parents complain that the new schools are far away, not very good and it is difficult to get all the paperwork done to get their children in.

If it is being done simply for the children, the authorities should take over these functioning migrant schools or give parents more time to make alternative arrangements, wrote one newspaper commentator following a similar plan.

Zhang Zhiqiang, who runs a website in Beijing providing educational information to migrant workers, believes there are dark forces at work.

"The real reason they are doing this is to reduce the cost of managing millions of migrants, by making life difficult and driving them back to their home provinces," he said.

Government statistics issued earlier this year show there are now as many as seven million people in Beijing from other places. The total population is 19 million.

Other policies suggest officials are becoming worried about the growing numbers of migrant workers in the capital.

They have placed limits on people living in basement rooms - just the kind of cheap accommodation used by migrants.

For the time being, the parents of children still at the Dongba school can only wait and see how this particular story ends.

Mother Wu Fang, who has enrolled her two children at the school for this new term, said migrant workers like her were at the mercy of the government.

"If they want us to go to the school, we'll go. If they say we can't, we won't. We're migrant workers - we have no power, no status and no rights," she said.

- Published17 August 2011

- Published12 July 2011

- Published29 June 2011

- Published1 November 2010

- Published7 March 2011