Burma's displaced Rohingya suffer as aid blocked

- Published

The BBC's Jonah Fisher takes a rare look inside the Rohingya camp, where conditions are described as among the worst in Asia

Six months of sectarian violence has driven more than 100,000 people from their homes in western Burma.

Rakhine Buddhist and Rohingya Muslim communities that have lived separately for generations are now forcibly segregated.

Barriers have been erected across roads in the state capital and thousands of Rakhine have had their homes destroyed.

But its the Rohingya who endure the worst conditions. Rejected as citizens by both Bangladesh and Burma, they continue to be victimised in the camps where they sought shelter.

On Myebon peninsula, south of the Rakhine state capital Sittwe, the double standards are clear.

Once the site of a daring amphibious raid by Allied troops in the Second World War, the peninsula is now home to two very different refugee camps.

Just a mile or so apart, they are populated entirely on ethnic lines - one for displaced Buddhists and the other for the Rohingyas.

Near the centre of town is the smaller of the camps.

On lush grass thirty five tents bearing the logo of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia stand in ordered rows. This is Kan Thar Htwat Wa, home to 400 Buddhists who have been here since clashes in late October.

Phu Ma Gyi 's home was burnt down and, with her two daughters, she now shares a tent with three other families.

"The government is looking after us here," she says. "We have food, medicine and what we need."

Not far away the Burmese and UN officials who I am travelling with are being shown a table full of medical supplies and bags of rice. It is clear there are no shortages here.

Blocked deliveries

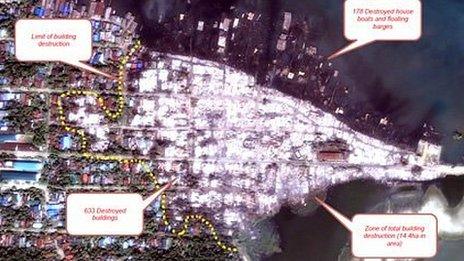

A short drive in the back of a truck takes us to the Rohingya camp. On the way we pass by what was the Muslim neighbourhood.

Now it is completely flattened, with just the outlines of houses still visible on the ground.

Khin La May was headmistress of the local Rohingya primary school, now destroyed

Six weeks ago, one of those outlines was the primary school where Khin La May was headmistress.

"The Rakhine community came with knives and threw stones and sticks," she said.

So she fled, along with 4,000 other Rohingya to a small mound just outside town. That mound became what is now Taung Paw Camp.

It is a squalid muddy mess with raw sewage running through its open drains. The tents are ramshackle and the people inside hungry and desperate.

Aid workers told me this is one of the worst camps in Asia, if not the world.

Deliveries to both camps on Myebon have to be made by boat, and attempts to get proper sanitation and supplies into Taung Paw have so far been blocked.

Rakhine Buddhists control the jetty and are refusing to allow aid agencies regular access to the Rohingya camp, thwarting attempts to improve conditions.

Burmese Border Affairs Minister Thein Htay said it was not up to the military to intervene

It is a scene repeated in other locations in Rakhine. One major aid agency told me obstruction by the Buddhist community was preventing them from doing 90% of their work.

Given the local objections only the Burmese military could force the aid through. But they have so far refused to do so.

Instead they stand guard at Taung Paw, stopping the Rohingya leaving to tend their crops (the Rakhine have in their absence taken the fields over).

Burma's Border Affairs Minister Thein Htay visited both the Myebon camps with us and said that military were keeping the Rohingya inside for their own security.

The stark difference in conditions was due to the camps being different sizes, he said.

"There is some disturbance by the local people," he said. "In your country does the military always intervene? The Burmese military is not the ruling man. There is the government."

Better relations

In Rakhine's urban centres the situation is better. Relations between the authorities and international aid agencies have improved and many of those displaced in June are being moved into better conditions.

UN representative Valerie Amos was shown food supplies at the Rakhine camp on Myebon

As she travelled to both Buddhist and Rohingya camps, the United Nations' top humanitarian official Valerie Amos repeatedly urged reconciliation.

For now with tensions high that appears a distant goal.

More money is needed to fund the Rakhine aid operation, Ms Amos said, but it is now up to the Burmese authorities to take a strong stand.

"The donors have a responsibility because we need more money to really be effective but the government also has a responsibility," she said.

"They have to take the lead. They have to show the leadership they have to work to bring the communities together. And that work has to start now."

- Published9 November 2012

- Published27 October 2012

- Published3 July 2014